In numerous countries, more restrictive regulations on abortions have recently led to a weakening of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). These legislative developments at the national level are reflected in the discussions at international forums, as they hinge upon human rights standards and access to health services. Although Germany has always advocated for the broad protection of SRHR, it is striking that the German government is not very active in international forums when it comes to addressing the content of this set of rights. This approach of diplomatic restraint carries the risk of providing those who oppose a broad interpretation of SRHR – be they governments, organisations or individuals – with a means to undermine the concept. If the German government wants to pursue its international commitment to human rights and individual freedoms in global health as well, more active advocacy is required.

The action programme of the International Conference on Population and Development, adopted in Cairo in 1994, defines sexual and reproductive health and rights as the full physical and mental well-being related to all aspects of sexuality and reproduction. Since the programme’s adoption, “sexual and reproductive health and rights” has been a recognised term in international law; the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) interprets it in an identical way. “Sexual and reproductive health and rights” is a collective term for a variety of topics related to sexuality, reproduction and gender identity.

Nevertheless, there is always a discursive struggle over the scope of what is meant by sexual and reproductive health and rights, a struggle that has recently intensified. At stake is nothing less than an attempt to undermine international norms by reinterpreting the content of these rights – so-called norm spoiling – and reducing the effectiveness of SRHR within the core area of health care for pregnant women, mothers and newborns. In doing so, norm spoilers deliberately exclude issues such as access to contraceptives and safe abortions, as well as protection against discrimination.

The debate about the scope of SRHR is not only relevant from a normative perspective and important for the political actors who are involved for ideological reasons. The different interpretations also have real consequences, since SRHR – among the proponents of a broad interpretation of SRHR – is considered an essential part of universal health care. Ultimately, a broad interpretation that includes abortion would exclude the justification of a ban on abortion based on the national cultural context, since the pursuit of universal health care is a universal concept that knows no regional restrictions.

Politicising SRHR

The controversies surrounding SRHR have led to greater politicisation of the topic, that is, to an approach from a primarily political perspective, and to its instrumentalisation as an election campaign issue. In this context, particular emphasis is often placed on the individual elements of SRHR, such as safe abortions. Discourses in various European countries, the end of Roe v. Wade in the United States and debates in international forums testify to the numerous efforts by conservative, fundamentalist and authoritarian forces to undermine SRHR. The issue of abortion in particular stands out in the controversial debates on SRHR. Due to the special attention paid to this question worldwide, it is suitable for exemplifying the process of undermining individual aspects of SRHR in international forums.

The United States as a case study

The United States is an example of how foreign and development policy is also subject to the influence of changes in government: With the “Mexico City policy” announced in 1984, the then-Republican US government under Ronald Reagan restricted the use of bilateral development funds with the effect that recipients were not allowed to use them to finance any abortion-related measures (the so-called Gag Rule). All non-governmental organisations operating abroad that offered support for abortions in addition to the measures actually eligible for funding were thus excluded from support. In fact, it was sufficient for the organisation to merely provide information on abortions in order for it to be excluded. The following democratic US administrations regularly removed the Mexico City policy, whereas every Republican administration reintroduced it.

In the wake of the growing influence of conservative forces in the United States, such as the Heritage Foundation, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), created by George W. Bush, has become the focus of the political dispute surrounding the Mexico City policy. PEPFAR is one of the most important instruments in the fight against HIV/AIDS worldwide. Most recently, the programme was exposed to the unfounded accusation from the Republican side that it supports abortions. Additional financing of the initiative, which has so far been supported by both parties, was delayed, and in March 2024 the programme was not extended for five years as it had been before, but only for one year.

Health consequences

The erosion of SRHR and the barriers to safe abortion access have immediate consequences for global public health, especially for women, LGBTIQ+ people and marginalised groups. According to WHO data, about six out of ten unintended pregnancies end in induced abortions, that is, abortions that are performed with the intention of terminating a pregnancy. About 45 per cent of all such induced abortions worldwide take place in unsafe conditions. These abortions are unsafe due to the lack of qualifications of the people performing the procedures, unsanitary conditions, dangerous methods and/or a lack of support. Approximately 7.9 per cent of the global maternal mortality rate can be attributed to unsafe abortions, with restrictive abortion laws increasingly leading to unsafe abortions.

Norm-spoiling with SRHR

In 1994, the Cairo Programme of Action recognised the importance of reproductive rights by explicitly including reproductive health and sexual freedoms in an international document for the first time. Regarding abortion, states were to address unsafe abortions by ensuring access to safe abortion care and post-abortion care, where it was consistent with national law. One year after the Cairo Conference, the Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in 1995, further contributed to the perception of safe abortion as a public health issue. Moreover, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action calls upon states to review their laws that impose penalties for illegal abortions.

In addition to these specific documents, SRHR are mentioned in several international agreements and conventions, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). As early as 2000, the United Nations (UN) Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) stated in its General Comment No. 14 that SRHR are a core element of the international right to health. It also reaffirmed this in General Comment No. 22, with reference to the Cairo Programme of Action. This sets the framework for the obligations of the states party to the ICESCR towards their inhabitants in the area of reproductive health.

Through “general comments”, “recommendations” or “concluding observations”, various UN treaty bodies repeatedly point out the need to comply with standards. Both CEDAW and the ICESCR require the states parties to submit regular reports to the UN Secretary-General on how they are implementing their obligations at the national level. In addition, various treaty bodies have repeatedly called for the decriminalisation of abortion under certain circumstances, such as in cases of health risks to mothers or rape. In a landmark decision, the CEDAW Committee, referring to a specific sexual offence (L.C. v. Peru), explicitly called on the government of Peru to decriminalise abortion in cases of rape or sexual abuse.

From the outset, the achievements of the SRHR approach at the global level have also been met with criticism. Although the controversies surrounding SRHR and abortion are not a new phenomenon, they seem to be taking on a new quality at the national and international levels, particularly due to the strengthening of ultra-conservative and, in some cases, right-wing extremist and religious fundamentalist voices. It is noteworthy that such actors usually do not reject SRHR per se, probably because of the degree of linguistic integration and codification achieved in several international treaties. Instead, they weaken SRHR norms by questioning their content and scope.

The targeted undermining of norms is often referred to as “norm spoiling”. The term describes the attack on agreements, norms and rights with the aim of weakening or abolishing them sooner or later. A number of actors engage in deliberate norm spoiling, from individuals and civil society organisations such as C-Fam, to states and groups of states. All of these forces are thus characterised by their joint efforts to undermine international SRHR norms. However, they differ in their motivations. In Russia and Hungary, for example, pro-natalist arguments predominate, that is, the desire to create conditions for as many births and children as possible, while states such as Nicaragua base their positions on Christian values. Other actors, such as Poland under PiS leadership and Brazil under the Bolsonaro administration, also resorted to anti-immigrant rhetoric to criminalise abortions. Furthermore, the various arguments often overlap. Pro-natalist goals can also be pursued from a religious perspective, for example; however, they can also be found in Viktor Orbán’s xenophobic rhetoric when he calls for restrictions to abortion rights while at the same time propagating the narrative of the “Great Replacement” theory.

SRHR at the WHO Executive Board

The current struggle surrounding the recognition and content of SRHR in international forums can be illustrated by the minutes of the meetings of the WHO Executive Board. Thirty-four member states are represented on the Executive Board for a period of at least three years. One of the main tasks of the Board is to prepare the agenda of the World Health Assembly. Only topics that have been discussed in the Executive Board may be addressed there. Many of the agenda items approved in this way are not even raised. In contrast to the Assembly, the Executive Board is able to hold extensive debates on the most important aspects of global health.

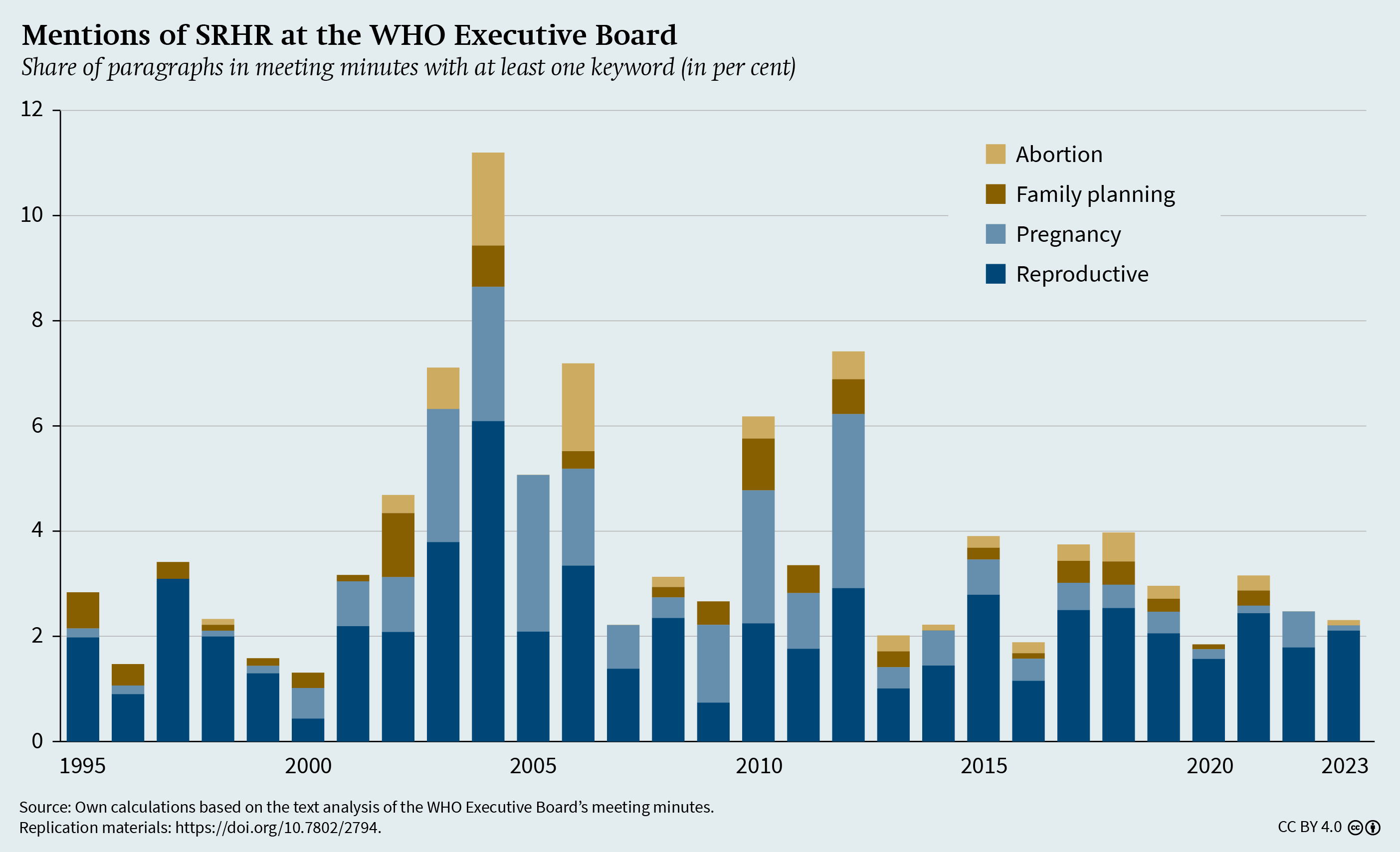

A comprehensive picture of how SRHR are dealt with in the WHO Executive Board can be obtained through a text analysis of the individual meeting minutes. To do this, all minutes between 1995 and 2023 were analysed, and individual paragraphs were searched for keywords in the context of SRHR (see replication materials). The search terms used were “abortion”, “family planning”, “pregnan*” and “reproduct*” (see Figure 1). The term “sexual” was not used because it is also used in contexts other than SRHR. Although SRHR topics, as measured by the term “reproductive”, appear in an average of 2 per cent of the paragraphs, only a few of them are about abortions. It is noteworthy that, at the beginning of the 2000s, SRHR discussions mentioned pregnancies, abortions and family planning more frequently than in the 1990s. Since then, the frequency of discussions on these topics has declined significantly and remained at a consistently low level.

In addition to this quantitative analysis, it is worth considering the few cases in which SRHR and, in particular, abortion are explicitly addressed. Although the majority of states emphasise the relevance of SRHR, they do not elaborate, for diplomatic reasons, on which aspects they believe are included in SRHR. Only Canada has always emphasised that SRHR includes “comprehensive sexuality education, contraception and safe abortion and post-abortion care” (WHO Executive Board, 152nd session, p. 195). On the other hand, countries such as Brazil, Zambia and the United States under the first Trump administration explicitly opposed such a broad interpretation in meetings, mainly by defining what does not belong to SRHR in negative terms (WHO Executive Board, meetings 148 and 144). The discussion about the scope of SRHR is thus largely dominated by proponents of a narrow interpretation of the rights associated with it, although no country participating in the Executive Board meetings, with the exception of Russia, rejects SRHR.

It can be seen, then, that SRHR have been mentioned continuously since the mid-1990s, and that the treatment of this complex of issues is explicitly supported by a majority of states. Nevertheless, there has been a simultaneous decline in the discussion of individual topics concerning SRHR. The comments on this that are documented in the minutes are limited, as outlined above, mainly to the opponents of a broad interpretation of SRHR.

The Geneva Consensus Declaration

In addition to the actors mentioned, a number of post-Soviet states, countries with a predominantly Catholic population and various Islamic fundamentalist countries have in the past positioned themselves against certain SRHR and women’s rights in general. These efforts received the support of the Arab League, the G77 and the United Nations African Group. Belarus, Egypt and Qatar went a step further and founded the Group of Friends of the Family in 2015. The group opposes certain aspects of SRHR and explicitly advocates the goal of strengthening the “family”, which in their view must always consist of a man and a woman in a marital relationship. It rejects abortion and UN processes and policies that aim for gender inclusivity. Other countries, such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Egypt, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia, subsequently joined the group.

The efforts of these and other norm-spoilers finally culminated in the Geneva Consensus Declaration on Promoting Women’s Health and Strengthening the Family, which was adopted in 2020. In this declaration, more than 30 countries, under the leadership of the Trump administration, signed a statement in which they committed to protecting the right to life from the moment of conception as a priority. The signatories refer to statements from the action programme of the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 and the Beijing Declaration of 1995, as well as to other human rights documents and declarations, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In their statement, they cite those passages that refer to the primacy of national legislation and reject abortion as a method of family planning.

These statements by the anti-abortion activists, however, are not only intended as a signal for domestic policy; they also aim to prevent access to safe abortions from being recognised as part of universal health coverage, as this would have further health policy implications. These mainly consist of the fact that states could be required under international law (e.g. under the ICESCR) to ensure universal health care for the population, including SRHR.

With regard to abortion, the Geneva Declaration states that access to health services for women should be improved and guaranteed. It explicitly includes sexual and reproductive health issues, but explicitly excludes abortions. On the other hand, it emphasises that there is no international right to abortion, but that regulations in this regard can only be enacted and amended at the national and local levels. The declaration thus recognises SRHR, but excludes abortion from those rights. Whereas the Cairo Conference Programme of Action also refers to medical follow-up care for unsafe abortions, the Geneva Declaration deliberately omits this reference. Similarly, although the Declaration refers to the Beijing Declaration, it ignores the appeal contained therein for states to review their national laws in order to avoid the negative consequences of unsafe abortions. Three months later, shortly after taking office, the Biden administration withdrew from the Geneva Declaration and opposed it. However, this did not lead to the project being abandoned. On the contrary, since then, other countries have joined the document, such as Georgia and Paraguay.

As can be seen from the examples given, language is an important factor in the process of norm spoiling, both through the rejection of already established formulas and the introduction of new wordings and interpretations. Thus, norm spoilers rarely seem to attack international SRHR as such – even if this might be the goal in the long run – but instead use different definitions of SRHR or interpret the contents differently. Discussions in international forums such as the WHO Executive Board and the World Health Assembly show that various actors are seeking discursive shifts, with already noticeable consequences for the understanding of international norms of SRHR and public health. For example, WHO data show that maternal mortality rates have recently stagnated or even increased in almost all regions of the world, which is partly attributed to national and international political trends.

The German position on SRHR

The German government regularly uses various strategies and action programmes to position itself on international law in general, and on the defence of SRHR in particular. In their concept for a feminist foreign and development policy (see SWP-Studie 7/2024), the Federal Foreign Office (AA) and the BMZ are committed to consistently strengthening SRHR worldwide, stating that the criminalisation of abortions leads to a higher prevalence of maternal mortality. In the guidelines for feminist foreign policy, the AA describes how the increasing tensions and the “split in the international community” are creating difficulties for the maintenance of established rights of women and LGBTIQ+ persons, and specifically of SRHR. In this context, the AA promises to vigorously defend the protection of these rights in the international system. Although the German government thus recognises and rejects the attempts of some actors to weaken existing law, it also wants to work to establish new norms.

One example of this is Germany’s efforts in 2019 to pass a resolution in the UN Security Council on sexual violence in armed conflicts. Some of the wording in the text proposed by Germany led to heated discussions and protests by other actors. The Trump administration in the United States threatened to veto the resolution and even pushed for the deletion of any mention of sexual and reproductive health and rights. In the end, a version of the resolution that made no mention of SRHR was adopted, with Russia and China abstaining.

Similar disputes have also arisen between various member states of the European Union (EU), most recently during the hearing of the designated Hungarian health commissioner, Olivér Várhelyi, who also took the position that regulations regarding access to safe abortion are not part of SRHR, but rather a purely national matter that does not fall within his area of responsibility as commissioner.

In international forums such as the WHO Executive Board and the UN Security Council, the Federal Republic of Germany adopts a cautious approach for diplomatic reasons and seeks consensus, whereas opponents present their positions with maximum demands and threats. Meanwhile, the failure of relevant resolutions, the increasing attempts to undermine the SRHR and the numerous national regressions regarding access to safe abortions reveal that the German government’s conciliatory approach is currently not very successful. A confrontational approach could be more effective. Such an approach could be modelled, for example, on Canada’s strategy, which regularly counters attempts at norm spoiling by explicitly speaking out against them.

Counter-norm-spoiling

An important factor that needs to be given more consideration in any future German and European policy efforts regarding SRHR and general women’s and human rights is the potential fragility of existing norms. In the future, norm spoilers could have an even greater impact on the linguistic reinterpretation of international norms. The liberal-democratic interpretation of these norms is not automatic and is vulnerable to morally ultra-conservative rhetoric, which is currently gaining strength at the international level. A heightened awareness of the tactics and capabilities of these actors is a prerequisite for finding effective and sustainable responses to their approaches. One possible reaction to the shift in discourse would be to become just as explicit and not allow the norm spoilers to control it. However, if the defenders of reproductive health and rights focus solely on issues of abortion law, there is a risk that other aspects of the topic, such as contraception, preventing or combating sexually transmitted diseases, and education measures, will fall by the wayside. Nevertheless, questions about abortion law are at the centre of international debates, and therefore clear language should be used in this matter if a human rights-based policy is desired.

One example of how sexual and reproductive health projects and measures can be incorporated into foreign policy strategies is France’s international policy on SRHR for the period 2023–2027. In its foreign policy guidelines, France takes an explicit position, for example, on access to safe abortions. Specifically, France provides financial support for access to SRHR services from the Muskoka Fund. The fund was set up following the 2010 G8 summit in Muskoka, Canada, and has since been financing the measures of various UN agencies to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in the area of SRHR, and to reduce maternal and infant mortality rates in 10 French-speaking African countries.

In 2018, Denmark also joined the financing of the fund. France would certainly be an appropriate partner for Germany if it were to set itself the goal of promoting similar measures, and thus contribute towards “counter-norm-spoiling” at the international level. Instead of working towards new norms under the umbrella of SRHR, as Germany attempted to do with the UN Security Council resolution, for example, the German government could work with these partners in international forums to focus primarily on defending existing norms and implementing them, including through foreign and development policy strategies. On this basis, the following specific recommendations can be made for German and European policy:

-

If the goal of German policy is to discursively strengthen SRHR, its representatives in international forums should also advocate more strongly for the retention of existing norms through decisive action and unambiguous formulations. This would help to ensure that norm spoilers fail in their efforts to control the definitions of SRHR concepts.

-

In addition, Germany should clearly articulate what it understands by relevant rights, such as access to safe abortion, in the discussion about the scope and implications of SRHR. This does not mean unrestricted legalisation, as opponents often claim, but rather the decriminalisation of abortions with time limits or under certain circumstances, such as rape or health risks due to pregnancy.

-

With regard to the EU, it is advisable to first decide whether a common position can be adopted in international fora in view of the often divergent positions on SRHR in different member states. If no common position can be found at the EU level, the German government should seek out suitable, like-minded partners, such as France, for the debates in international forums, even at the risk of then no longer speaking with a common EU voice.

-

Strengthening SRHR at the global level requires stable structures that partners can rely on, regardless of changes in government policy. One way to achieve this would be to provide flexible multi-year budgets, as in the development policy context, for new and established programmes, especially for civil society organisations that work independently of governments and must be positioned to counter norm spoiling.

Franziska Schwebel is a Research Assistant in the EU / Europe Research Division at SWP. Dr Michael Bayerlein is an Associate in the EU / Europe Research Division. Dr Pedro A. Villarreal is an Associate in the Global Issues Research Division.

The authors work on the SWP project “The Global and European Health Governance in Crisis”, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (BMG).

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C55

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 61/2024)