At least since Russia deployed North Korean artillery and ballistic missiles against Ukraine, it is obvious that Pyongyang fuels conflicts far beyond North-East Asia. Yet, the indirect threats that North Korea poses to Europe’s security and stability have developed a new quality: Pyongyang is actively supporting Russia’s and Iran’s security policy goals by supplying ammunition for fighting the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. North Korea has thereby raised its strategic value for Moscow and Tehran. This allows Pyongyang to expand and exploit these partnerships in service of its own interests and to jointly expand and secure supra-regional networks for violating sanctions and engaging in smuggling. The EU needs more information and international cooperation in order to understand Pyongyang’s practices and to identify and use opportunities to shape the current situation.

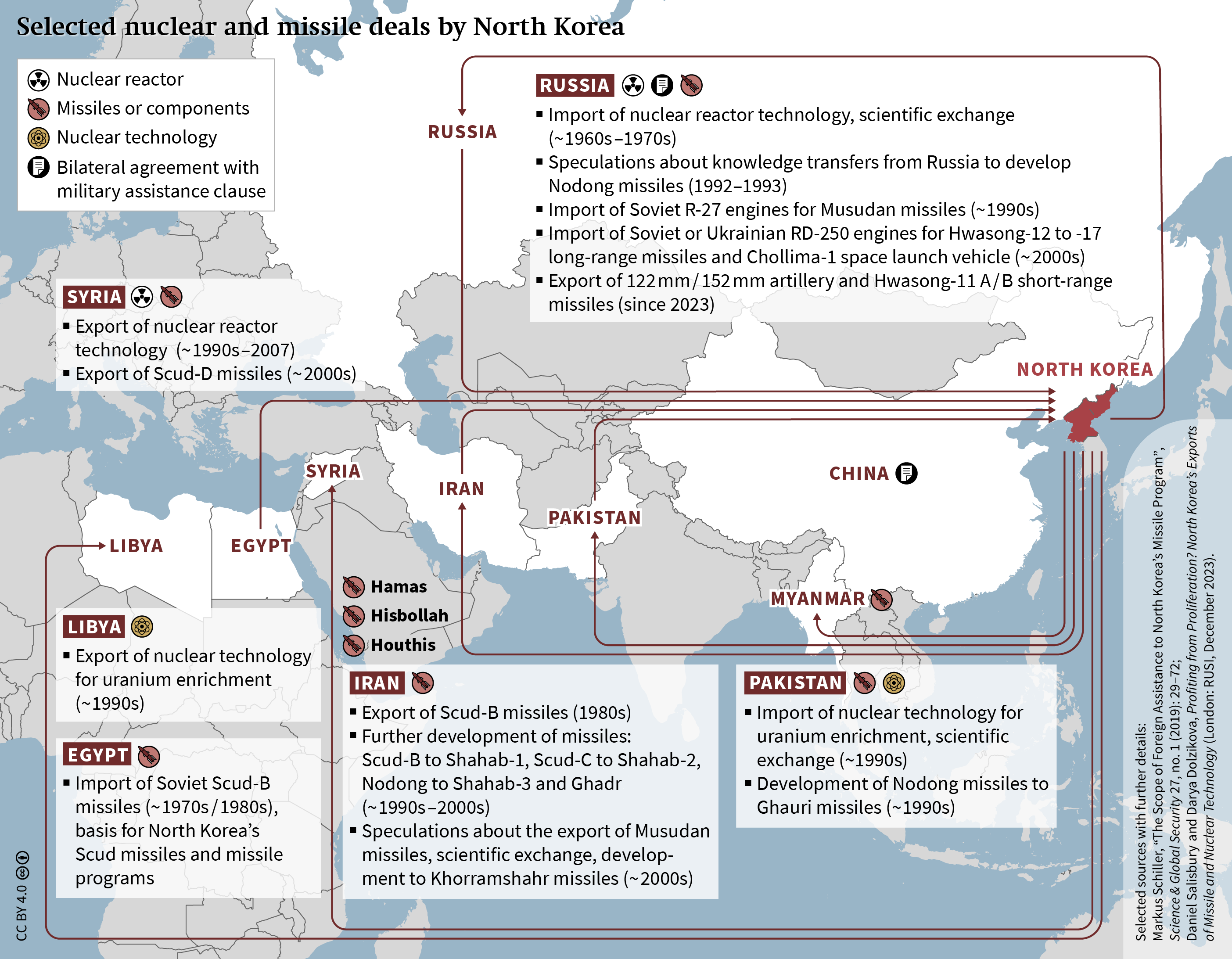

Until recently, North Korea was considered more of a regional security threat, and its nuclear proliferation was mainly seen as a challenge to global norms. Instability on the Korean peninsula and risks of further proliferation continue to pose indirect threats to European security, but Pyongyang has increased its threat potential. Its nuclear weapons programme builds the framework for a significant expansion of its arms policy and related partnerships. The geopolitical situation and regional wars have occurred at a favourable time for North Korea. Pyongyang can use its successful missile programmes and large stockpiles of artillery and ammunition to intensify partnerships and gain external resources and know-how for its nuclear modernisation and further development of its military capabilities.

Admittedly, it is extremely difficult to analyse the nature and scope of North Korea’s arms deals. There is hardly any confirmed information or reliable reports. Instead, there is lots of speculation. In addition, Pyongyang itself is using denials and propaganda to fuel uncertainties and worst-case fears.

Ammunition for Moscow’s war of attrition against Kyiv

Artillery and missiles are Moscow’s most effective means of wearing Ukraine down in the long term. Here, Russia has clear quantitative advantages due to its own stocks and production as well as thanks to willing suppliers.

Regarding artillery, Pyongyang plays the role of a decisive supplier. According to estimates, North Korea may have exported up to 13,000 containers with 6 million artillery shells to Russia during the past two years. Combined with its own annual production capabilities (almost 3 million shells), Russia would be able to use 5.5 million artillery shells against Ukraine each year. Moscow’s self-imposed target of launching 5.5 million shells/year corresponds to the actual firepower (based on an average of 15,000 shells/day according to western calculations) that the Russian military employed throughout 2022 to conquer and hold large areas of Ukraine. This is significantly higher than the current average of 10,000 per day. Ukraine would need around 1 million artillery shells per year for its defence – the US and Europe currently produce around 1.2 million shells per year.

For now, North Korea is probably relying on its old artillery stockpiles to export such volumes – this would also explain the dud and failure rate of up to 50 per cent that Ukraine has documented. According to Pyongyang’s own statements, however, its arms industry is currently running at full speed. South Korean estimates assume that North Korea is capable of producing around 2 million artillery shells per year.

North Korea has also supplied at least 50 of its most modern short-range missiles along with launch vehicles – significantly fewer than the 400 missiles that Moscow reportedly received from Tehran. Russia is using these additional weapons to replenish its missile stockpiles, presumably to destroy Ukraine’s critical infrastructure more effectively and at a higher cost-efficiency. Until now, to target critical infrastructure, Moscow has mainly used drones with significantly less firepower and air-launched cruise missiles, which are much more expensive to produce. Using the mass of cheaper missiles from Iran and North Korea, Russia could quantitatively overwhelm Ukraine’s sometimes very successful air and missile defence systems.

It is difficult to calculate how many missiles North Korea will deliver to Russia. The exported missile system also serves as a tactical nuclear weapons system against South Korea and is therefore an important element in Pyongyang’s deterrence posture. North Korea should thus want to keep its deliveries limited. Yet, it is striking that Pyongyang is not exporting any of its large stockpiles of older short-range missiles to Russia. North Korea is presumably giving in to Moscow’s purchasing wishes and in return is learning from the employment of its modern systems for its own plans.

A new win-win arms deal for Moscow and Pyongyang

North Korea’s munitions deliveries to Russia are changing the quality of their relationship. Previously, it was Moscow that indirectly supported Pyongyang’s arms programmes and related export policy – now North Korea can offer decisive weapons itself and demand significant concessions. Against this backdrop, North Korea has likely succeeded in ensuring that the new partnership agreement with Russia once again contains a clause of mutual military assistance, which Pyongyang uses as proof of its alliance with Russia for a projection of power.

The partnership agreement also promises cooperation in the areas of nuclear technology, satellite technologies, and satellite launch vehicles, which would indeed be plausible equivalents of the ammunition deliveries. Moscow could thereby help North Korea with its ambitions to produce more fissile material (for nuclear weapons) and develop its own space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. While doing so, Russia could argue that it still does not (directly) support Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons and missile programmes.

However, the most important win-win aspect of their partnership may be the coordinated circumvention of sanctions against them. Russia’s and North Korea’s arms industries require external resources like semiconductors. Both would therefore benefit from jointly expanding and securing their smuggling businesses and networks. Analyses of North Korean and Russian missiles debris in Ukraine show that Moscow and Pyongyang are still able to procure electronic components internationally.

Arms deals between Tehran and Pyongyang

Russia is not Pyongyang’s only customer. North Korea and Iran have long-standing defence relations with cooperative traits. However, given the progress and successes of their respective missile programmes, it is unclear whether Iran and North Korea continue to cooperate as extensively in the field of missile technologies as they did in the past. Nevertheless, to a certain extent, both sides could still benefit from cooperating with one another.

Regarding missile technologies, Pyongyang could help Tehran build long-range missiles, such as by sharing the engines with which North Korea successfully operates its latest intermediate and intercontinental ballistic missiles and satellite launch vehicles. However, Iran declared that it needs missiles with ranges of only up to 2,000 kilometres and it already owns satellite launch vehicles. There are similar speculations that Pyongyang has supplied Tehran with engines for medium- to intermediate-range missiles.

Notably, Tehran has not employed North Korean missiles since the Iran-Iraq war, but only its own, as it did recently against Israel. Yet, there are isolated reports that Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthi militias also use missiles and ammunition of North Korean origin. It would be plausible for Tehran to act as a mediator and buy additional ammunition for these militias, so as not to overburden its own stockpiles.

It is striking that there are no substantive reports of Pyongyang and Tehran exchanging information or materials in the field of nuclear technology. This lack of evidence contrasts with known attempts of how North Korea wanted to profit from exporting nuclear capabilities to Libya, Pakistan, Syria, and other locations via online marketplaces. Should Iran wish to develop a nuclear weapons programme, Pyongyang’s capabilities could be useful. Tehran can already produce weapons-grade fissile material itself, but support on how to use this material to build nuclear warheads would be a particular show of trust by North Korea.

Conversely, Iranian assistance in the areas of drone technology and energy supply would be relevant for Pyongyang, but there are no hints at such support. Yet, Iran could opt to reward North Korea with such assistance in return for more ammunition to Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. In the meantime, it is in both countries’ immediate interests to circumvent international sanctions and procure electronic components for their respective arms industries.

Policy options for Europe

To understand the nature and extent of the indirect threats to Europe’s security and stability that North Korea poses, more intensive analyses are required. However, this requires more intensive information gathering and closer exchange of information within NATO and with partners in the Middle East, Indo-Pacific, and Central Asia. The recently established Multilateral Sanctions Monitoring Team is a first step in this direction, but it requires broader participation.

A more detailed analysis of the problem is necessary so that the EU and individual states in Europe can identify possible levers of influence. Europe can hardly prevent North Korea from co-operating with Russia and Iran. However, Brussels could create incentives for third countries, banks, and companies that – knowingly or not – are involved in North Korea’s money laundering, weapons deals, and procurement activities for its arms industry. Public reporting about this can increase pressures to act, but European states and their partners would need to create a new, universally accessible, and systematic information basis. United Nations (UN) reporting on North Korea’s sanctions violations is no longer possible since May 2024 given Russia’s veto power in the UN Security Council. The EU can also use its existing dialogues, for example with Indo-Pacific states on non-proliferation, to this end. A more direct lever would be the expansion of maritime domain awareness and the interdiction of suspicious vessels in international waters, but such proactive measures would require even greater incentives to disrupt North Korea’s arms trade. One approach in this direction would be to identify synergies between maritime security and non-proliferation and engage in capacity building with Pacific partners that benefits both, the EU and its partners.

Elisabeth Suh was a researcher in the International Security Research Division until the end of September 2024. This paper is published as part of the Strategic Threat Analysis and Nuclear (Dis-)Order (STAND) project.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C49

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 53/2024)