Escalations Risks in the Horn of Africa

Threats from Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia Exacerbate Local Conflicts

SWP Comment 2024/C 50, 28.10.2024, 8 Seitendoi:10.18449/2024C50

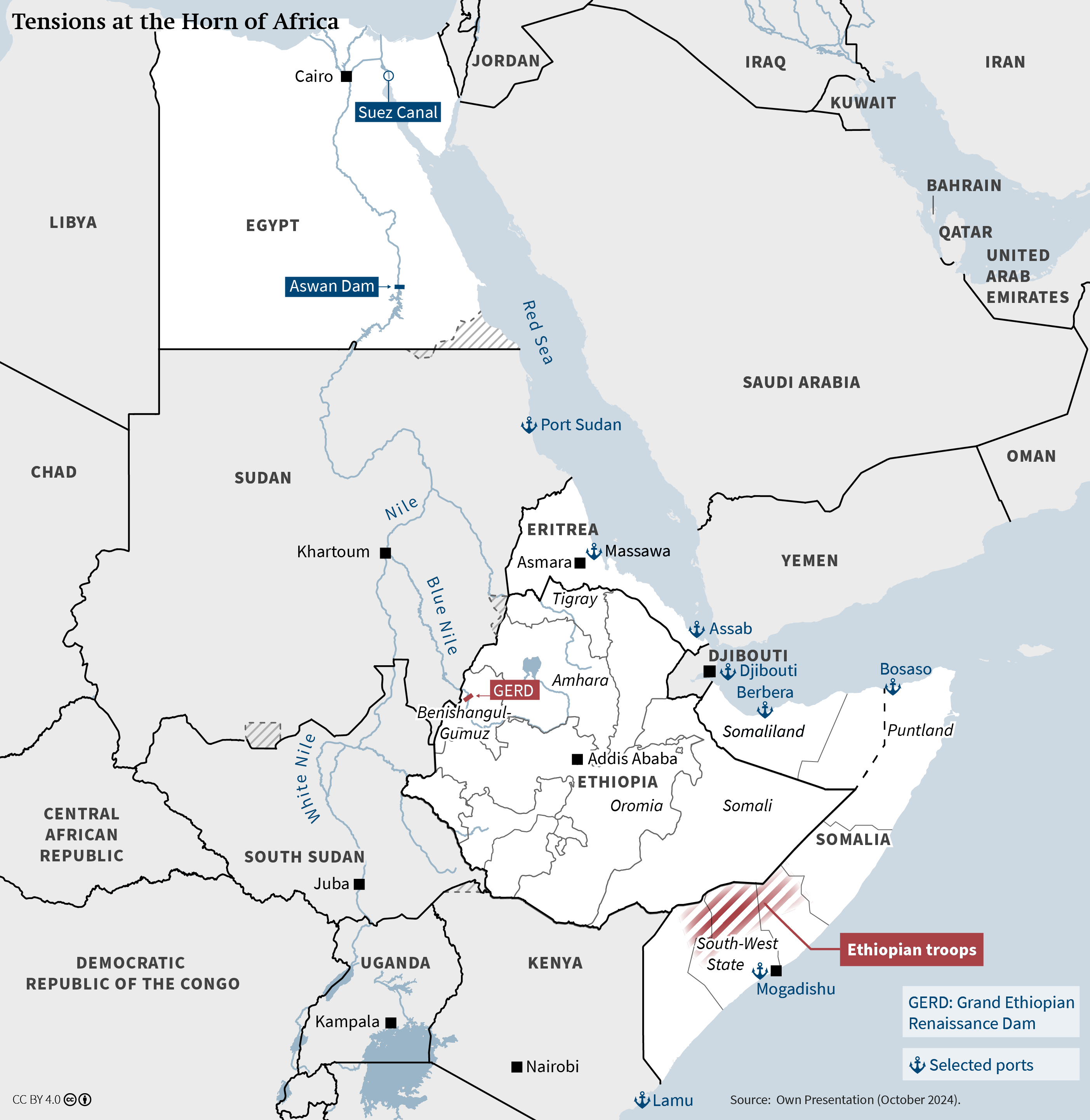

ForschungsgebieteIn recent months, relations between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Somalia have deteriorated significantly. Previously separate disputes have become intertwined: namely the conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia over the use of Nile waters and the disagreement between Ethiopia and Somalia regarding the recognition of Somaliland. The three countries use threats to improve their respective positions in these conflicts. While an inter-state military escalation does not seem imminent at present, regional tensions are likely to rise, which could further empower the jihadist Al-Shabaab militia in Somalia. Germany and the European Union (EU) should recognise the highly complex interdependence of these lines of conflict, remind the countries concerned of their common interest in stabilising Somalia, and continue to advocate for dialogue in the Nile dispute. At the same time, it is also important to hold other influential actors more accountable to contribute to regional stability.

The immediate trigger for the current tensions is the supply of weapons from Egypt to Somalia as a result of a security agreement signed by the two countries in August 2024. In addition, there were reports that Egypt, with agreement from Somalia, is planning to send several thousand soldiers to the Horn of Africa to fight Al-Shabaab and replace the Ethiopian troops that have been stationed there thus far as part of the African Union (AU) mission, which expires at the end of this year. In response, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed warned that his country would “humiliate anyone who dares to threaten us”. Apparently as a deterrent, the Ethiopian military deployed heavy weapons at the border with Somalia.

In Somalia, the foreign minister threatened to support armed groups in Ethiopia if Addis Ababa did not stop its steps towards diplomatic recognition of Somaliland. Somalia has received support not only from Egypt, but also from Eritrea: At a tripartite summit in October in Asmara, the presidents of the three countries agreed to intensify their security cooperation. At almost the same time, Egypt lodged a complaint with the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), accusing Addis Ababa of jeopardising its water security by commissioning the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Ethiopia, in turn, claimed that Egypt had repeatedly threatened it with violence. It is apparent that two central conflicts in the Horn of Africa are becoming increasingly interlinked and are therefore intensifying.

Egypt’s water worries

Egypt’s conduct in the Horn of Africa can also be explained by its long-standing dispute with Ethiopia over the use of the Nile’s water. This past summer, the conflict has once again intensified with the fifth phase of filling the GERD’s reservoir. For Egypt, which meets over 90 per cent of its water needs from the Nile, the construction of the gigantic dam since 2011 at the upper reaches of the Blue Nile poses a significant threat to its own water supply and therefore to national security. For years, Ethiopia has been vigorously pushing ahead with the completion of the dam project, which is intended to significantly contribute to meeting the country’s immense energy needs. In contrast, Egypt insists on its right to veto construction projects on the upper Nile and on a bilaterally agreed water sharing formula with Sudan. Cairo attributes both rights to treaties from the colonial era, which Ethiopia and the other upstream riparians reject as they were not part of these treaties.

Diplomatic efforts to resolve the water dispute, including the GERD negotiations in which external actors such as the United States of America (USA), the AU, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) mediate, have largely stalled. The same applies to cooperation within the framework of the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), which was established in 1999. In recent years, Cairo’s negotiating position has increasingly deteriorated. On the one hand, construction on the dam is significantly advanced, with the project nearing completion and electricity production already underway. The third and fourth turbines were connected to the grid in August 2024, with the rest of the 13 turbines due to follow in the coming months. On the other hand, Egypt has lost its key ally in the water conflict. Sudan, which long supported Egypt and pursued its own water interests, has effectively withdrawn from the negotiations as an independent actor due to its ongoing civil war. Khartoum also benefits from the GERD, particularly from protection against regular flooding.

In addition, with South Sudan’s ratification in July, the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) came into force in October 2024. This agreement establishes the permanent Nile River Basin Commission (NRBC), which initially includes six upstream riparian states, albeit excluding Egypt and Sudan. Concluding a framework agreement between all 11 riparian states, which sets out the principles, structures, and institutions for joint, basin-wide water management, was one of the main objectives of the NBI. However, since upstream and downstream riparian states failed to agree on such an accord for over ten years, Egypt and Sudan were ultimately left out when the CFA was signed in May 2010 by Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda, and Rwanda – followed soon after by Kenya and Burundi. After all signatories except Kenya had ratified the agreement, South Sudan became the sixth state that needed to implement the CFA.

Egypt’s attempts to bolster its negotiating position on the Nile through security agreements with various states in the region, such as South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Rwanda, have thus far been proven unsuccessful. Even after President Abdelfattah al-Sisi and Prime Minister Abiy agreed at a face-to-face meeting in Cairo in July 2023 to resolve the outstanding issues within four months, no progress was made. As a result, Egypt has started to intervene in the conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia to also exert pressure on Addis Ababa.

Ethiopia’s port ambitions

While Ethiopia and Somalia had previously maintained close diplomatic relations for several years, bilateral relations have rapidly gone downhill since the beginning of 2024. The reason? The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by Prime Minister Abiy and President Muse Bihi Abdi of Somaliland in January. The MoU, the text of which has not been published, stipulates that Ethiopia will lease a 20-kilometre coastal strip for 50 years to establish a naval base there. In addition, Ethiopia is to be given economic access to a harbour of the de facto state. In return, Ethiopia promised Somaliland a stake in Ethiopian Airlines and held out the prospect of considering the recognition of Somaliland as an independent state.

To date, no UN member state has recognised Somaliland’s independence, which the autonomous region proclaimed in 1991. Nevertheless, various states maintain primarily economic relations with Somaliland. For example, the UAE has invested several hundreds of million USD in the expansion of the port of Berbera, which is operated by the Emirati company DP World since 2017, as well as in logistical infrastructure with Ethiopia on both sides of the border. At the time, Ethiopia and DP World signed an agreement under which Addis Ababa was to contribute 19 per cent of the port expansion. However, Ethiopia lost this claim in 2022 after the war-torn country failed to provide the promised funds.

With the MoU, Ethiopia is now taking a different approach to achieving its goal of its own access to the sea. Abyi’s government sees this as compensation for a “historical mistake” made by his predecessors when they granted Eritrea independence in 1993 and thus gave up access to the sea. As a result, Ethiopia is now the most populous country without a coastline. Around 95 per cent of all Ethiopian imports and exports currently pass through the port of Djibouti. The annual fees for this are up to around US$1.5 billion, which Ethiopia must pay in scarce foreign currency.

The leadership in Mogadishu firmly rejected the MoU. Somalia views the recognition of Somaliland by Ethiopia, which could be followed by other states, as a violation of its sovereignty. In April 2024, Somalia expelled the Ethiopian ambassador from the country and withdrew its own representative from Addis Ababa. Meanwhile, Ethiopia appointed an ambassador to Somaliland in August 2024.

Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud successfully sought diplomatic support, both in the region and from international players, including the G7 states. In this context, Somalia and Egypt concluded a security agreement in August 2024. It was on this basis that Egypt delivered weapons to Mogadishu two weeks later.

Risk of war between Egypt and Ethiopia

Military threats from Egypt in its water dispute with Ethiopia are not new. However, a direct Egyptian attack on the GERD construction site was long considered unrealistic due to the limited range of Egypt’s Air Force. Furthermore, Egypt, as a downstream state, would not achieve its main objective through military action, as Ethiopia could then deliberately reduce the Nile water flow at the dam to exert pressure on Egypt. Now that the reservoir is filled, such an attack also harbours unpredictable risks for the water flow of the Nile and would trigger a catastrophic flood in Sudan. Nevertheless, the deployment of Egyptian troops in Somalia could increase the risk of a direct military conflict between the two countries.

Should hostilities actually occur, Cairo would undertake considerable risk. Although the country has by far the largest armed forces in Africa and an extensive arsenal of weapons, this does not necessarily translate into actual military power. For example, the armed forces suffered heavy losses in the fight against insurgent groups in the Sinai Peninsula after 2013. It was only in the past two years that the security situation was gradually brought under control. Despite having troops stationed in Somalia, a military operation outside its own borders would be much more challenging, not least due to the distance, while Ethiopia could act from its own territory. Should armed action by Egypt result in massive losses or even failure, this could lead the Egyptian population to openly question the role of the armed forces in the country’s politics and economy. Civil society is already critical of the army’s preoccupation with managing a vast, inefficient economic empire.

There is also no conceivable international and regional backing for military action. Cairo is heavily dependent on the Gulf States and the USA. The UAE, in particular, has become Egypt’s most important state creditor in recent years. Meanwhile, the USA provides around US$1.3 billion annually in military aid, which makes up an integral part of Egypt’s defence budget. As both countries also maintain close relations with Ethiopia, an Egyptian military move could jeopardize this critical financial support.

Cairo’s actions are therefore unlikely to aim at a direct military confrontation with Addis Ababa. Rather, the threat of escalation is intended to persuade external actors to become more involved in the Nile water dispute on Egypt’s behalf. There has been no such internationalisation of the conflict to date, although Cairo has sought this for years. Above all, Cairo would like to see Ethiopia’s regional opponents strengthened militarily.

In addition to local groups in Somalia and Ethiopia, Cairo is likely to focus on Eritrea. Asmara’s relations with Ethiopia have deteriorated significantly since 2022 when Eritrea fought alongside Ethiopian troops against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Eritrea opposes the Pretoria Agreement between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF, which ended that war, as it thwarted Eritrea’s goal of destroying the TPLF once and for all. Border disputes and Ethiopia’s quest for direct access to the sea, possibly again in Eritrea, are further exacerbating tensions. As a result, Asmara has emphatically intensified its relations with Cairo. The summit between Egypt, Eritrea, and Somalia in October is a visible sign of that rapprochement. Nevertheless, Eritrea is unlikely to simply become Egypt’s stooge. Instead, it would rather pursue its own interests in the medium term, namely the establishment of a buffer zone on Ethiopian territory. The Ethiopian federal government currently appears to tolerate the presence of Eritrean troops in northern Tigray.

Nevertheless, a direct clash between Egyptian and Ethiopian troops cannot be completely ruled out should Cairo actually station a significant number of soldiers in Somalia. This risk increases all the more if Ethiopia refuses to withdraw its troops from Somalia. Egypt could cite the defence of Somali interests and create a naval blockade of Somaliland, or in the worst-case scenario, attempt to expel Ethiopian troops.

A “game of chicken” between Ethiopia and Somalia

Two factors significantly mitigate the risk of an armed conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia: the military balance of power and shared interest in fighting Al-Shabaab.

While Ethiopia’s army is strongly involved in fighting several insurgencies and weakened by the 2020–22 war in the north of the country, it remains one of the largest military powers in the region. It possesses drones, helicopters, fighter planes, and heavy weaponry, among other equipment. In contrast, the Somali security sector remains a work-in-progress. It is not even able to effectively protect Mogadishu from attacks by Al-Shabaab. The Somali security forces are divided between units under different commands of the federal government, the federal member states, and clan militias that operate incoherently. Despite successes in training some units, the Somali security forces remain heavily dependent on international military and financial support, including from the AU, EU, USA, Turkey, Kenya, and Ethiopia.

Ethiopia and Somalia have long been united in the fight against Al-Shabaab. Addis Ababa wants to contain the jihadist group’s capabilities in its neighbouring country, maintain a buffer zone, and thus prevent it from attacking Ethiopia. In July 2022, hundreds of Al-Shabaab fighters crossed the border and advanced around 150 kilometres into the Ethiopian interior until they were repelled. The invaders are said to have included many Ethiopian nationals from the Somali and Oromia regions.

Due to this threat situation, Ethiopia is currently deploying around 10,000 of its own soldiers in Somalia. Only about a third so far have been part of the AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS). Addis Ababa has deployed the rest on its own initiative. These troops co-operate closely with those of the respective Somali federal member states and local militias. The Somali federal government had tolerated these troops for years (similar to Kenyan units in the south of Somalia) because they serve to provide security in their areas of operation.

The threatening behaviour of Ethiopia and Somalia reflects this unequal balance of power. Ethiopia is calculating that Somalia cannot afford to expel the Ethiopian troops from the country because they are making a decisive contribution to the fight against Al-Shabaab. In this logic, Somali reactions to the MoU with Somaliland would thus fizzle out. Conversely, the Somali government has now announced that if Ethiopia does not withdraw the MoU then Ethiopian troops need to leave the country by the end of December 2024 when ATMIS ends. Somalia is counting on the fact that Ethiopia cannot afford to withdraw. The question is who will give in first.

Escalation of internal conflicts as the real danger

While direct conventional armed conflict between the states involved is currently rather unlikely, both Ethiopia and Somalia are susceptible to both intentional and unintentional escalations due to their internal divisions.

The biggest risk is that the Ethiopian-Somali disagreements could further boost Al-Shabaab. The group has already been able to benefit from the partial withdrawal of ATMIS because Somali security forces thus far have been unable to fill the gap. In addition, the so-called Islamic State is spreading in Puntland.

It is still unclear what exactly the successor mission to ATMIS, whose mandate expires at the end of December 2024, will look like. In August 2024, the AU Peace and Security Council adopted an operational plan for a new mission under the name AU Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM), which is supposed to replace ATMIS in January 2025. However, it has not yet been clarified which countries will provide troops or how the mission will be financed. Egyptian troops could take the lead, along with a presumably smaller contingent offered by Djibouti. However, it remains to be seen who will provide the rest of the planned 12,000 soldiers (ATMIS currently has around 12,600). More troops from the current contributors, namely Kenya and Uganda, are possible. In principle, AUSSOM is planned to continue for five years, gradually handing over increasing responsibility to the Somali security forces.

If the Ethiopian troops do indeed withdraw and are replaced by Egyptian troops, the latter are likely to have difficulties controlling the security situation, at least during the transition period. The Ethiopian armed forces have built up local networks over more than a decade and have equipped and trained local militias. Egypt would first have to painstakingly establish these contacts. Meanwhile, Al-Shabaab could continue to spread both in Somalia and possibly on the border with Ethiopia. Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that weapons destined by Egypt for the Somali government could find their way to Al-Shabaab.

The AU is hoping for funding through a new mechanism created by the UNSC in December 2023. Under this mechanism, 75 per cent of future AU missions could be paid for from UN compulsory contributions. However, this requires approval by the UNSC. The UN and AU are scheduled to present a plan for the design and financing of AUSSOM by mid-November. The decision could come too late to guarantee a seamless transition from the current to the successor mission. For this reason, bridge financing is already being discussed, for which attention focusses on the most important source of funding to date: the EU. However, currently the EU opposes continued funding of an AU deployment.

Another dimension of the conflict is the relationship between the Somali federal government and Somali member states. There have already been several demonstrations in the Somali South-West State calling for the continued presence of Ethiopian troops. The President of the South-West State, Abdiaziz Laftagareen, also spoke out against the deployment of Egyptian troops and in favour of keeping the Ethiopian contingents deployed in his state.

Relations between Mogadishu and the federal member states are already strained. At the end of March, Puntland announced that it would withdraw from the country’s federal system after the federal government had pushed the first chapters of a constitutional reform through parliament. A few days later, Puntland representatives met with an Ethiopian state secretary. Ethiopia could continue to offer an open door to dissatisfied political stakeholders in Somalia in the future and thus influence the political situation there. There have been armed clashes between Somali federal member states and the government in Mogadishu at various times in the past. Somalia’s foreign ministry has already accused Ethiopia of supplying weapons to Puntland.

Conversely, Ethiopia is exposed to the risk that armed groups in the country could be supported from outside. For example, external support for the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) in Ethiopia’s Somali State would be conceivable. Although the ONLF declared a ceasefire with the government in 2018, the movement complained in September 2024 about Ethiopian troop deployments, which it saw as a “militarisation” of the state and threat to peace.

Other intervention possibilities exist in Amhara, Oromia, Benishangul-Gumuz (where the GERD is located), and Tigray. In the past, the Ethiopian government has repeatedly accused Egypt of supporting various armed groups in Ethiopia. These include Gumuz militias, which tried to block the main road to the GERD a few years ago, as well as the TPLF during the war in the north.

The currently most active centres of conflict in Ethiopia are the regions of Amhara and parts of Oromia. The Fano militias in Amhara have benefited from past training by Eritrean forces– a support that may still be ongoing. In August 2024, Ethiopian and Kenyan intelligence services reported a cooperation between the Oromo Liberation Army, which is fighting the Ethiopian government, and Al-Shabaab in Somalia.

Policy options for Germany and the EU

Germany and its European partners should take the geopolitical tensions in the Horn of Africa seriously and ensure that they are not exacerbated by one-sided positioning or ill-conceived financial incentives. Although an inter-state war is currently unlikely it cannot be completely ruled out due to misunderstandings, ill-considered missteps, and emotional responses on all sides. In any case, the tensions are making further regional cooperation more difficult at a time when there are already major challenges in the region: the war in Sudan, the Houthis’ attacks on shipping in the Red Sea, and the strengthening of Al-Shabaab and the so-called Islamic State in Somalia.

It is important that Germany and the EU think about the complex conflicts in the region together and not in isolation. Europeans should not allow themselves to be tempted by the power games of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia to support unilateral agendas in the name of dubious promises of stability.

Regarding Somalia, the Europeans should make it clear that transitional financing of AUSSOM from the European Peace Facility must not play to the hands of Egypt’s threat against Ethiopia. A possible compromise could be that if Somalia insists on Egyptian military involvement, such troops could be stationed in Mogadishu to train security forces there, while Ethiopian troops continue to directly support the fight against Al-Shabaab in other states. The EU should continue to reject the unilateral recognition of Somaliland under international law.

In the conflict over the utilisation of the Nile water, Germany and the EU should work to ensure that the NRBC is not exploited by individual riparian states to further weaken Egypt’s position when the CFA will be implemented. The NRBC should only be supported if its activities are truly basin-wide, comply with international legal standards, and thus implicitly protect Egypt’s Nile water interests. The Europeans should also work to maintain the NBI for the exchange of information on Nile water issues between NBRC members and other riparian states or to establish a comparable low-threshold (dialogue) platform that all Nile riparian states can join without obligation.

Finally, Europeans should continue to endeavour to better coordinate their overall engagement in the region. External actors with influence on the concerned governments should also be held accountable to promote conflict resolution approaches. Turkey is already serving as a mediator between Ethiopia and Somalia, albeit so far without success. The UAE has a special role to play: It has strong economic interests in the Horn of Africa, particularly through investments in harbour infrastructure and agriculture, and is one of the most important state creditors. Financial aid and – in the case of Ethiopia – military support have contributed significantly to the consolidation of power of the current political leaderships in Cairo and Addis Ababa and increased their willingness to take foreign policy risks. Nevertheless, the UAE has lacked vision for regional order. Its contribution to constructive conflict resolution remains small – a fact that should be addressed more assertively with Abu Dhabi.

Dr Gerrit Kurtz is an Associate and Dr Stephan Roll is a Senior Fellow in the Africa and Middle East Research Division. Tobias von Lossow is a Research Fellow at Clingendael – Netherlands Institute of International Relations.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C50

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 52/2024)