The negotiations on the Brexit withdrawal agreement are heading for the endgame: An agreement is to be reached in October – at the latest in November 2018 – if the United Kingdom is to leave the EU in an orderly manner in March 2019, as planned. But the EU-27 and the British government are still a long way from reaching this agreement. Above all, British domestic policy is unpredictable: There is neither a majority for any form of Brexit, nor a substantial change of opinion against Brexit, as such. Any outcome of the Brexit negotiations threatens to trigger a political crisis in the UK, further increasing the risk of a disruptive exit.

The Brexit negotiations are stuck in a temporal paradox – on the one hand, time is running out for the British and the EU-27, while on the other hand, the handling of Brexit will continue well into the 2020s. First, Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) sets a limit of two years to regulate the withdrawal of a member state from the European Union (EU). For the United Kingdom (UK), this deadline ends on 29 March 2019, when the country will leave the EU without a settlement if there is no agreement or extension of the deadline by then. In order to have time for the necessary ratification, the negotiators on both sides actually wanted to reach an agreement in October 2018; if necessary, a last-minute agreement would still be possible in November or December.

For affected citizens and businesses alike, this is very late: Nobody knows yet under what conditions EU citizens will be able to live and work in the UK from 30 March, and under what conditions they will be able to trade with the UK.

At the same time, a real clarification of the question concerning the future relationship still lies far in the future. The withdrawal agreement – if it is concluded – is intended exclusively to regulate the modalities of separation (rights of EU citizens living in the UK and vice versa, financial obligations of the UK, border with Northern Ireland) and to allow a transition phase until the end of 2020. During that transition, the UK is set to formally leave the EU, but it will remain in the Internal Market and Customs Union, bound by EU law. A political declaration on the withdrawal treaty is intended to outline the framework for the future relationship. The future relationship will, however, only be fully negotiated in detail during the transition until 2020 – or possibly even beyond. In short, the Brexit negotiations must start in autumn 2018 in a sprint, but only as part of a longer negotiation marathon.

Northern Ireland in Focus

In this marathon of negotiations, negotiators on both sides are already well advanced on separation issues, despite the difficult negotiations. According to joint statements, about 80 per cent of the withdrawal agreement is politically agreed, for example on the basic structure of the agreement, on safeguarding citizens’ rights (with some exceptions), on the financial obligations of the UK, and on the modalities for the transition phase. But these agreements are meaningless if no agreement is reached on the overall package – including the transition phase.

As in most negotiations, the remaining 20 per cent are the most controversial. Technical issues with high political relevance are still open. These include, for example, the question of the institutional mechanisms for implementing the withdrawal agreement, i.e., what rights the EU Court of Justice will have. The protection of geographical indicators in the UK after Brexit (e.g. Champagne, Nuremberg gingerbread, etc.) – an important economic factor for the EU worldwide – is also still a point of contention.

The biggest obstacle, however, is how to deal with the Irish-British border in Northern Ireland. This future EU external border is of enormous importance for EU member Ireland, both because of its importance for the Northern Ireland peace process and because of the close economic ties between the two parts of the island (see SWP Comment 7/2017). With 208 border crossings, the border also has more crossings than the entire EU external border in Eastern Europe – de facto it is hardly controllable and therefore of great importance for the EU as a whole. From the beginning of the Brexit negotiations, the EU-27, supported in particular by Germany, have made keeping this border open a central criterion for a withdrawal agreement.

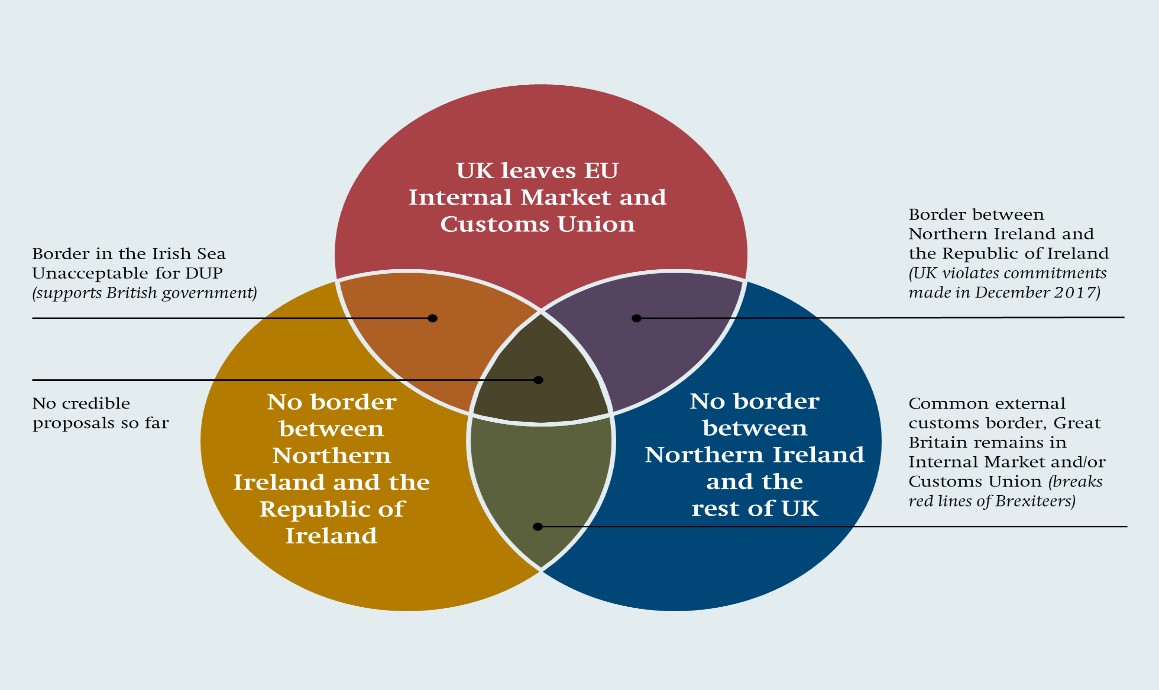

At the same time, the internal contradictions of Brexit are in focus with the border in Northern Ireland. The British government has set three incompatible targets (see Figure 1): Prime Minister Theresa May has always stressed to her own people and party that Britain will leave the EU’s Internal Market and Customs Union. Anything else is dismissed as a betrayal of the referendum. In December 2017, however, the British government promised the EU-27 to keep the border open in any case. To this end, the withdrawal agreement is to spell out a “backstop” option with which the border can be kept open, even if this cannot be guaranteed by the general British-European relationship – theoretically, even if the EU and the UK fail to agree a future trading agreement. Finally, May has promised the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which supports the government, not to create controls between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

Since then, the negotiations on Northern Ireland have stalled. The British government categorically rejects the proposal for a backstop presented by the EU Commission in March 2018 (“No Prime Minister could ever sign this”). This saw the creation of a common regulatory area between the EU-27 and Northern Ireland, with the latter effectively remaining in the Customs Union and parts of the Internal Market. This is regarded in the UK as breaking up the integrity of the United Kingdom itself, not least because the Scottish government also wants a special status vis-à-vis the EU for Scotland. However, the British government has not yet presented its own proposal. The rejection of the EU-27 proposal, on the other hand, is shared by all parties in the UK. The best way to mitigate the backstop would be a statement on the future relationship, with the prospect that it would never be needed.

Wide Front against Chequers

But it is precisely this political declaration that is the second major obstacle. For a long time, the British government has been negotiating mainly with itself about the future relationship, while the EU-27 have stood firm on a clear position: The UK should be integrated into the EU’s existing relations with third countries, i.e., either participate in the Internal Market with all rights and obligations, as Norway does, as part of the European Economic Area, or conclude a deepened free trade agreement with the EU as a third country, such as Canada. The latter would allow tariff-free trade but result in significant cuts in market access for workers and (financial) services, and exclude the UK from the EU’s common regulatory area – and thus also trigger the backstop for Northern Ireland.

In July 2018 Theresa May, under intense political pressure, gathered her government behind the strategy named after the location of the Chequers plan meeting. According to the strategy, the UK wants to keep a “common rule book” with the EU’s Internal Market for goods. The country is also to remain in the Customs Union in the medium term until new technical possibilities for a solution have been found. In contrast, May’s strategy proposes removing the remaining freedoms for services, capital, people, and other EU policy areas from Britain. The EU rules should also not apply to purely domestic products either, and the British Parliament would retain a principal veto right (but with consequences if the UK decides to deviate from EU rules). This strategy is being sold to the EU-27 by May as the only acceptable solution in the UK.

The Chequers plan is being rejected by the hard Brexiteers in the UK as well as by the EU-27. EU opponents such as conservative MPs Jacob Rees-Moog and Boris Johnson see Chequers as a plan to bind the UK in the long term to a “vassal status” vis-à-vis the EU in which it (partially) accepts EU legislation without having a say. EU negotiator Michel Barnier and all national governments of the EU-27, on the other hand, have made it clear that although parts of the Chequers plan are a good basis for negotiations, the central proposal – partial participation in the Internal Market without legally binding enforcement – violates the EU’s central red lines. This would divide the four freedoms, endanger the Internal Market, and at the same time allow British companies to gain unfair competitive advantages over their EU competitors.

In short, to cushion the backstop in Northern Ireland, the political declaration on the future relationship between the EU and Britain should be as specific as possible. But the more detailed the statement becomes, the more the EU will insist on its red lines on the integrity of the Internal Market and demand more concessions from the British. This, in turn, increases the risk of the withdrawal agreement failing in the British Parliament.

A High-risk Political Game

The most critical element in the Brexit negotiations in the short term is the volatility of British domestic policy. For internal political reasons, the British government has already made a legal commitment to submit the withdrawal agreement and political declaration to the two houses of Parliament. Only after it has gained approval from the House of Commons can it sign the withdrawal agreement with the EU. But that approval is more than uncertain:

First of all, May only has an extremely narrow majority. Since she called snap elections in June 2017, she has headed a minority government. The current 315 Conservatives, backed up by 10 members of the Northern Irish DUP, only achieve a majority among the 650 seats because the 7 members of the Irish Nationalist Sinn Fein from Northern Ireland do not accept their seats. Even a handful of dissenters can cost May her majority at any time. The pressure comes from at least four sides.

Firstly, the hard Brexiteers in the Conservative Party categorically reject the Chequers plan, and even more so any further concessions to the EU. According to their own statements, the Tories assembled in the “European Research Group” (ERG) have up to 80 MPs who are willing to vote against the government on Chequers. At least 25 have made this public, including former ministers David Davis and Steve Baker, who resigned in protest against Chequers. In the past, the ERG has repeatedly managed to impose hard interpretations of the Brexit vote in the Conservative Party and Parliament with threats against the Prime Minister to vote against the government. This group also has enough deputies to initiate a leadership challenge against Theresa May in her party at any time – but not enough to make her own candidate Prime Minister. By rejecting the withdrawal agreement, however, they could enforce the “WTO scenario”, which they see as their preferred option. Crucially, at least in public, they play down the costs of a no deal Brexit – despite most economic studies stating otherwise – arguing that after a short-term hiccup, Britain could recover, and even gain, by signing free trade deals around the world and undercutting European regulations.

On the other side of the spectrum, at least 12 members of the Conservative Party can be identified who openly advocate the closest possible ties to the EU. In theory, they too have the possibility of costing the government the majority if the entire opposition vote against it as well. In the course of the parliamentary process on Brexit, they have succeeded, among other things, in strengthening the House of Commons’ decision rights on Brexit (“meaningful vote”). In the past, this group flirted time and again with rebellion against the government and only failed to gain a majority in the House of Commons for a Customs Union with the EU against the wishes of the government because five Labour MPs voted with the government. Although they could cost the government the majority, they are less likely to risk a no deal outcome than the ERG.

The Northern Irish DUP is the third Achilles’ heel of May’s minority government. The DUP is itself a conflict party in Northern Ireland and stands for a clear unionist course. The party is a staunch supporter of Brexit, even though the majority of Northern Ireland’s population has voted for remaining in the EU. The party’s self-image and raison d'être, however, is its attachment to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. For the DUP, this is much more important than Brexit or the survival of the May government. The 10 DUP MEPs have therefore openly threatened to withdraw support from the May administration if it enters into an agreement with the EU that would in some way lead to a differentiation between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom. This is true, according to the party’s public statement, even if it is only an option of last resort, as with the “backstop”.

The fourth crucial factor is Labour as the main opposition party, which, with its 257 MEPs, could help May gain a majority at any time. Indeed, the Labour leadership around Jeremy Corbyn has clearly accepted the Brexit vote. Labour has therefore in the past voted with the government in favour of triggering Article 50. However, the party has submitted six tests for the withdrawal treaty – formulated in such a way that no form of Brexit will ever fulfil them – and has already announced its intention to vote against the withdrawal agreement.

The rejections by the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish National Party are even clearer. Politically, none of the opposition parties have an interest in taking responsibility for the Brexit result. Furthermore, particularly Labour is speculating on early elections in the event of May’s failure. Although Labour is also divided on Brexit issues, in the past only five pro-Brexit Labour MPs voted with the government.

In a nutshell: There is currently no majority in the British Parliament for any Brexit variant. While Theresa May has to fight for every vote for approval of the withdrawal agreement and political declaration, the opposition cannot be expected to help. If both the DUP and even some of the 25 MPs who form the core of the ERG vote against her, she has hardly any chance to get an agreement through Parliament. If only one of these groups rebels, she would still have to fight for every single MP to get over the line.

The Clock Is Ticking

In light of these differences, the outcome of the Brexit negotiations is still completely unknown. Five scenarios are on the agenda for the medium term. Two factors are important for the evaluation of these scenarios. On the one hand, the default option in Article 50 negotiations is not a return to the status quo, but rather the UK dropping out of the EU on 29 March 2019 without any transition or rules governing future cooperation. On the other hand, not all open questions need to be clarified before withdrawal, but rather “only” the withdrawal agreement and the political declaration on the framework of future relations.

Scenario 1: Orderly Brexit

The scenario that the negotiators on both sides are working towards is an orderly Brexit on 29 March 2019. This requires the EU-27 and the UK to have agreed by then the withdrawal agreement and the political declaration for future cooperation. From the standpoint of the EU-27, this has to include a legally binding backstop for Northern Ireland, the remaining separation modalities, and the transition. In order to have sufficient time for parliamentary approval and the implementation processes, an agreement in autumn 2018 is necessary. Furthermore, the British Parliament has set a deadline of 21 January 2019 for its government to conclude the withdrawal negotiations. Otherwise, the government will have to obtain approval for a new mandate from Parliament – which is likely to be difficult, given the majority situation outlined above.

If an agreement between the British government and the EU-27 is reached, a number of steps will still have to be taken. The most critical step is the vote in the British House of Commons. Looking at May’s recent speeches, the strategy of the May government to get its own parliamentarians to vote in favour is already taking shape: To give them the choice of either accepting the agreement May negotiated with the EU, or take personal political responsibility for the consequences of a “no deal” scenario and – addressed particularly at the Brexiteers – accepting the risk that new elections, a Labour government, and a second referendum could follow. If May succeeds in this, final approval is necessary on the European side from the European Parliament (EP) and the European Council. The EP has also set clear conditions for the Brexit negotiations – in particular the protection of civil rights and the open border with Northern Ireland. However, since this is largely congruent with the priorities adopted by the EU-27, simultaneous approval by the member states and rejection by the EP can be regarded as unlikely.

The UK could then leave the EU on 29 March next year in an orderly manner and remain in the Internal Market and Customs Union until at least the end of 2020 as part of the transition phase. Nevertheless, even an orderly Brexit does not mean the end of Brexit uncertainty. Because the political declaration can only outline future relations – legally non-binding – these have to be negotiated during the transitional period, with another cliff edge looming in January 2021.

Scenario 2: Extension

If the House of Commons rejects the outcome of the negotiations, or if the negotiators are unable to reach an agreement, a politically and economically very volatile situation threatens to emerge. A government crisis in London is then almost inevitable, as are new negotiations among the EU-27 on how to proceed. A fall of Theresa May and either a new Prime Minister from the Conservative Party or new elections are the logical domestic consequences.

The simplest way legally to defuse the situation between the EU-27 and the UK during this intra-British crisis would be to extend the negotiations in accordance with Article 50 TEU. This allows the parties to extend the negotiation period through a unanimous decision of the European Council of 27 in agreement with the UK. Legally, there are no limits to how long or how often the deadline can be extended. For example, an extension to the end of 2020, i.e., the currently planned transition phase, is conceivable. During the extended negotiation period, the UK would continue to be an EU member with all rights and obligations. In this context, it would also have to hold EP elections next May, which could easily turn into a vote on the Brexit process.

What is most critical, however, is that the supporters of Brexit have already legally anchored the exit date as part of the parliamentary process on Brexit. The British government can therefore only request or agree to an extension if it has obtained parliamentary approval. Since some of the supporters of Brexit within the UK Cabinet, such as Michael Gove, only support the government’s current strategy because they want to “cross the line”, such an extension would be at least as difficult to get through as a negotiated result.

Scenario 3: “Managed No Deal”

If there is neither agreement nor an extension of the deadline, the UK will leave the EU without any settlement, by automatic operation of law. In trade, this leaves WTO rules as a fallback, including the obligatory reintroduction of tariffs, while other areas – including citizen’s rights, the EU budget, justice and home affairs cooperation, and participation in EU regulatory schemes – have no such fallback options. The economic, political, and personal consequences would be very grave for the UK, but (to a lesser extent) also the EU-27.

The British government is therefore working in its preparations for non-agreement on the assumption that it can at least, to some extent, mitigate these consequences through a series of individual agreements – with the EU as a whole or bilaterally with its member states. In the spirit of such a “managed no deal”, the British government has already written to all 27 EU member states, for example to negotiate bilaterally about access to their airspace for British airlines in case of no deal. Representatives of the citizens concerned are also constantly calling for their rights to be safeguarded by means of a separate individual agreement, even if the overall talks fail.

The conditions for a “managed no deal” are, however, extremely poor: a volatile political environment in the UK, a negotiating situation in which negotiations conducted for two years would have failed, a potential withholding of British budget payments to the EU, a European Parliament in the middle of an election campaign, and an enormous flood of areas to be regulated give rise to doubts that amicable management without a withdrawal agreement is possible in the short term.

Scenario 4: “Disruptive No Deal”

The transition to the most negative scenario – a disruptive Brexit without any common rules – is therefore fluid. Legally, this remains the default option if there is no agreement: The UK leaves the EU without a transition phase, without any rules for EU citizens, and without any agreements for future cooperation.

However, even in this case, the administrations on both sides should, and will, work to avoid complete chaos. The EU Commission’s “Brexit Preparedness” communications therefore assume that, at least in the short term, only unilateral measures by both sides are able to limit the worst consequences. But even if planes still fly across the English Channel, the reintroduction of tariffs and the abrupt expulsion of the EU’s second largest economy from the EU’s single market alone will lead to considerable disruptions.

Even then, it will be necessary to maintain dialogue. Britain remains one of the EU’s most important neighbours in any Brexit scenario. Even if the cooperation of both sides would be impaired for years if no agreement were reached, in the medium and long terms, both sides will have to return to the negotiating table – even, and especially, after a chaotic Brexit – in order to pick up the pieces and make future cooperation possible.

Fringe Scenario: Second Referendum

One conceivable outcome of a failure of the negotiations – especially in the event of a rejection of the withdrawal agreement in the House of Commons negotiations – is a second referendum. In principle, European politicians such as the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, and French President Emmanuel Macron have again and again kept the possibility open for Britain to remain in the EU. At least until Brexit is formally implemented next March, the prevailing legal opinion is that it is legally possible for the UK to remain in the EU.

Politically, however, a second referendum is a long way off. First, there has been no substantial change in opinion against Brexit in the UK. Apart from a few outliers, surveys since 2016 show across the board that the country is still largely divided 50-50 on the question of EU membership, with only a marginal advantage for remaining.

Second, a second referendum requires a parliamentary vote, which is hardly likely to take place, given the current majority situation. Added to this is the time factor – the parliamentary procedure for the 2016 referendum took more than six months. A second referendum would therefore require new elections in the UK, the electoral victory of a party or coalition in favour of a second referendum, and, finally, an extension of Article 50 to hold that referendum.

This chain of events has become possible since Labour, at its party conference in September 2018, voted in principle for a second referendum as a fallback option. At the same time, the Labour leadership has sent conflicting signals whether “remain” should actually be on offer in such a referendum, or whether it should just be between no deal and a negotiated result of Brexit.

In short: A second referendum could not be organised by March 2019 and would only be possible after a political crisis in the UK, new elections, a Labour election victory, and a full commitment to revisiting the referendum.

Outlook

The Brexit negotiations are a “dance on the cliff edge”. Analysis of the negotiations has shown that falling off the cliff into one of the “no deal” scenarios remains a realistic option, despite both sides having a fundamental interest in reaching an agreement. Political and economic decision-makers should therefore prepare for the no deal scenarios.

The biggest challenges on the road to an agreement are inextricably linked: securing an open border in Northern Ireland, the political declaration on future relations, and obtaining parliamentary approval in Britain. Theresa May’s majority here is more than uncertain. Given the fragile situation in the British House of Commons, where no form of Brexit has a majority, any of the possible scenarios seems to lead to a political crisis in Britain.

Furthermore, the EU-27 and the UK government have made their red lines so clear that an agreement without loss of face on at least one side seems almost impossible. In terms of power politics, the EU is undoubtedly in a stronger position, as the UK would be more affected by any of the scenarios in the event of a disagreement. Nor can, or should, the EU resolve the self-inflicted blockade of British domestic politics by letting Britain pick the cherries from the single market or sacrifice the interests of its member Ireland to an agreement with London.

Nevertheless, the EU-27, and Germany in particular, should not lose sight of its long-term strategic goals in the sometimes heated negotiations: Yes, protect the single market, but also find a sustainable partnership with their future geostrategic neighbour, the UK. Beyond its red lines, the EU should therefore be ready to find a creative special solution for Northern Ireland. Finally, if talks break down, decision-makers on both sides should be open to accepting an extension rather than one of the no deal scenarios.

Dr. Nicolai von Ondarza is Head (a.i.) of the EU / Europe Division.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2018

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN 1861-1761

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 55/2018)