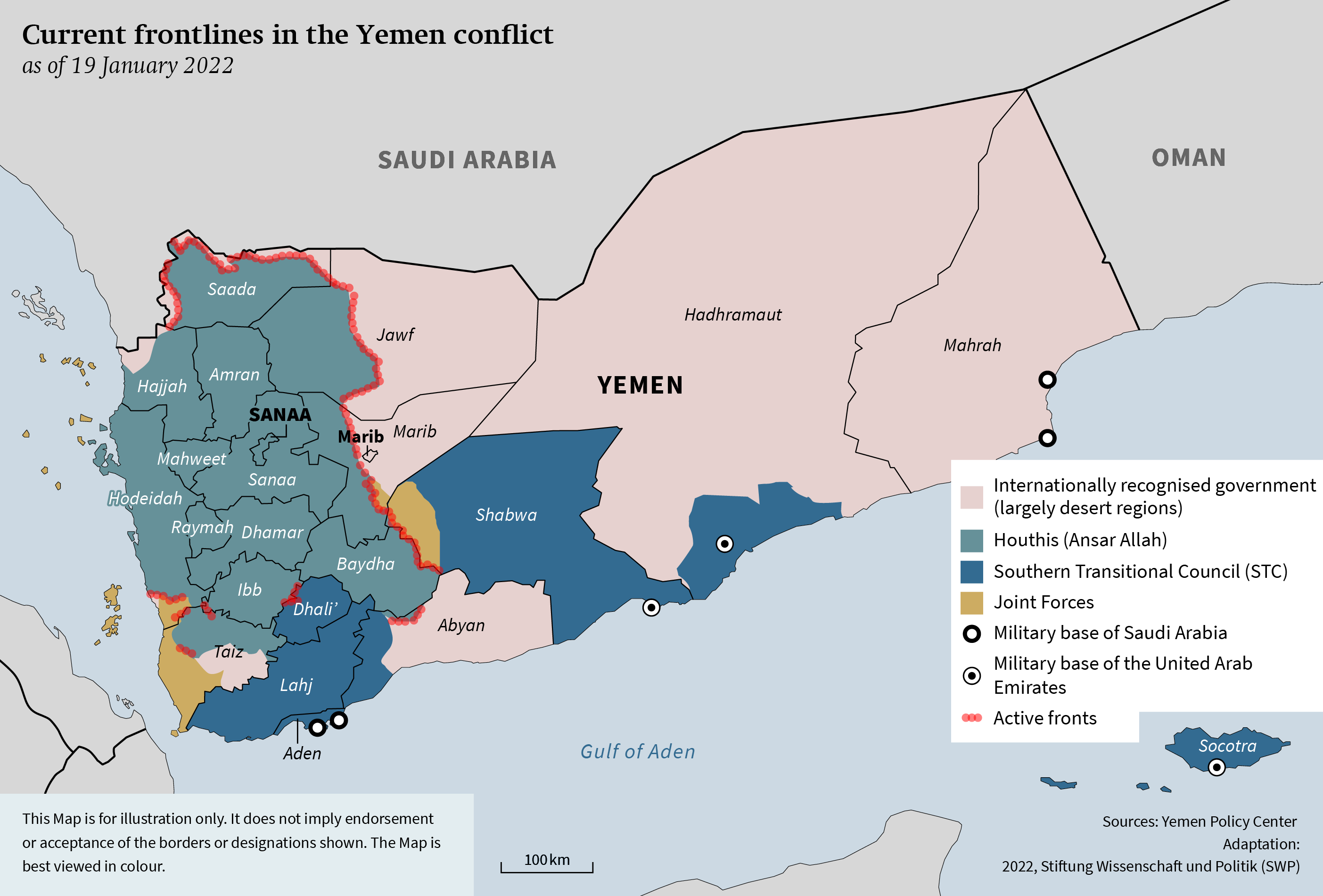

The future of the Yemen conflict will be decided about 120 kilometres east of the capital Sanaa, in the city of Marib. So far, the internationally recognised Yemeni government, supported by Saudi Arabia, has been able to ward off a two-year offensive from the Houthi movement, which originates from the north of the country and is aiming to take hold of the eastern provincial capital. The Houthis have had the military advantage, but as of January 2022, are being pushed on the defensive by the United Arab Emirates (UAE)-backed Giants Brigade, which is advancing into the governorate of Marib from the south. Conceivable scenarios for the course of the conflict are: 1) ceasefire negotiations after a successful defence of Marib; 2) the fall of the provincial capital as the starting point of a shift of the conflict to the southern parts of the country; or 3) a negotiated division of the country with participation of the UAE and Iran. Against this backdrop, Germany and its European partners should support regional powers’ attempts at rapprochement and begin discussing new political perspectives for the future of Yemen with civil society and parties to the conflict.

The loss of Marib, the capital of the oil-rich province of the same name, would considerably weaken the Yemeni government under interim President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi. After almost seven years of war, Marib is now its most important stronghold. Despite the support of the military coalition led by Saudi Arabia, the government has lost control over significant parts of the national territory and has been unable to retake the capital Sanaa, which the Houthis seized in September 2014.

The Houthi rebels, also known as Ansar Allah (“partisans of God”), originally hail from the northern region of Saada, bordering Saudi Arabia. Since forming a government in November 2016, the group has acted as the de facto authority in the country’s populous northwest. In March 2015, a military coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE had already intervened in the conflict to support the internationally recognised Hadi government. Riyadh was motivated by the fear that Iran could increase its influence on the Arabian Peninsula if the Houthis grew more powerful. In order to mediate between the parties to the conflict, Hans Grundberg, the fourth special envoy of the United Nations (UN), was appointed in August 2021.

So far, however, neither the UN mission nor the Arab military coalition has succeeded in achieving the goals defined in UN Security Council Resolution 2216, namely the withdrawal of the Houthis from the territories they have occupied since 2014, the return of the weapons stolen from the state stockpile and the restoration of the internationally recognised government in the capital. For Riyadh, the war has increasingly become a burden, in part because the Houthis are using missiles and drones to attack strategic targets in Saudi Arabia, such as airports and oil refineries. Moreover, the human rights violations and war crimes committed by the coalition have massively damaged the international reputation of the Kingdom. Instead of curbing Iranian influence, the military intervention has actually intensified the relationship between the Houthis and Tehran.

Although the Saudi government has repeatedly signalled that it is looking for a way out of the war, a withdrawal without an agreement would be a political embarrassment and would further endanger Saudi Arabia’s internal security, as continued attacks by the Houthis could not be ruled out. US President Joe Biden’s February 2021 promise to end the conflict through a diplomatic offensive has not been fulfilled. Proposals put forth by US Special Envoy Tim Lenderking and the Saudi government in March 2021 were rejected by the Houthis. Far from ending the conflict, American policy has actually emboldened the Houthis in their military action: first in February 2021 by Biden withdrawing former President Donald Trump’s designation of the Houthis as a terrorist organisation; and then by the US troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, which allowed the Taliban to depose the internationally recognised Afghan government, an act that is seen as a precedent by the Houthis.

The Houthi offensive reached its preliminary climax in autumn 2021 when the rebels began to besiege Marib from the north, west and south, taking control of parts of the southern oil-rich province of Shabwa. Once the UAE-backed Giants Brigade pushed the Houthis out of the province and advanced north into the Marib governorate, the rebels feared losing their advantage on the frontlines. Given that the party that holds Marib would have the upper hand in negotiations, the race for the city intensified. Against this backdrop, three scenarios emerge for the further course of the conflict, each with a different probability of occurrence.

Scenario 1: Negotiations between the Houthis and Hadi Government

The Houthis have little interest in entering into negotiations on an equal footing with others so long as they have a military advantage. The last agreement with the Hadi government brokered by the UN in December 2018 was only possible because at that time the Houthis were on the defensive on the battlefield and believed they could benefit from negotiations. After all, the agreement prevented an incursion by coalition troops into the geostrategically important port city of Hodeidah. A prerequisite for renewed peace talks is therefore a clear shift in the military balance in favour of the government troops. It is within this context that Tareq Saleh, the nephew of former President Ali Abdullah Salih, who was killed by the Houthis in December 2017, attempted to unite the anti-Houthi alliance. He commands the Joint Forces deployed in the southwest – a loose confederation of different armed groups backed by the UAE, including the Salafi-led Giants Brigade.

After the 15,000-man-strong Giants Brigade was re-deployed to Shabwa, the tide turned against the Houthis. With this advance, the coalition has made it clear that it is not willing to give up Marib as long as there is no agreement with the Houthis or their allies in Tehran. Despite the increased involvement of the Arab coalition, its medium and long-term commitment to the anti-Houthi alliance remains questionable. Over the last few years, Saudi Arabia has significantly scaled back its engagement in Yemen. Although the number of airstrikes has recently spiked, the Yemen Data Project reports that the intensity of Saudi airstrikes has dropped sharply since 2018, and financial support has also decreased considerably: since 2020, the Saudis have not paid the salaries of the Yemeni government or government troops. The UAE does not support the government given that the Muslim Brotherhood, which is active in Yemen in the form of the Islah Party, makes up the backbone of the internationally recognised government, particularly in Marib. At the same time, the UAE has until recently, shied away from direct confrontations with the Houthis.

Without continued military, financial and political support from both Saudi Arabia and the UAE, it is unlikely that the military balance will shift in a significant enough fashion to enable a sustainable resolution to the conflict. Beyond a ceasefire, it is unlikely that the parties to the conflict will agree to power-sharing. This is due, on the one hand, to the Houthi’s unwillingness to compromise; they have agreed to agreements in the past but failed to honour them. On the other hand, it is due to the flawed negotiating framework of the United Nations, which misunderstands the war as a two-party conflict and thus neglects local and regional actors. Even more problematic is that the UN approach, on the one hand, underestimates the power position of the Houthis and, on the other, overestimates their willingness to give up military gains in exchange for political participation in the Hadi government.

Scenario 2: Houthi Victory in Marib as the Beginning of a new North-South Confrontation

The capture of Marib by the Houthis would decisively change the dynamics of the Yemeni conflict. As Marib is the most important stronghold for the Hadi government, the loss of the city would send a shockwave through the government’s other fragile areas of control and lead to the gradual collapse of the Hadi administration. Although areas outside Houthi territory are nominally under the control of the Hadi government, much of it is in fact controlled by other armed groups, such as the Southern Transitional Council (STC) or the Joint Forces. The differences between the approaches and goals of the Saudi and Emirati interventions in Yemen were one of the lead causes of the fragmentation. While Riyadh’s priority was to push back the Houthis, and thus Iran’s influence on Yemen, the UAE’s policy was aimed at controlling the sea routes in the Red and Arabian Seas and at containing the Islah Party. Since the government’s army is largely made up of Islah Party troops, the UAE has supported other armed groups instead. These are linked to the government but ultimately pursue their own interests, a reality that led to the split in the anti-Houthi alliance. For example, members of the STC originally fought alongside the government, but – driven by a desire to lead the south to independence and supported by the UAE – increasingly separated from the alliance. In August 2019, the Hadi government was even driven out of the transitional capital of Aden by STC fighters. An agreement brokered by Saudi Arabia in November 2019 between the government and the STC aimed to bridge the rifts, however, it has yet to be fully implemented. Today, the STC acts as a quasi-government in and around Aden.

In the southern oil and gas-rich province of Shabwa, UAE-supported forces ousted the Islah Party from local government in December 2021, installing a governor that is more aligned with UAE and STC interests. On Yemen’s west coast, the Emirates support the Joint Forces under Tareq Saleh. Taiz, the most populous city in the west of the country and an important economic centre, is formally under government control but both politically and militarily ruled by the Islah Party. In turn, competing with government forces, the UAE maintains its own elite units in Hadhramaut.

In the event of a victory in Marib, it is unlikely that the Houthis would be satisfied with northern Yemen alone, hence they would claim the entire national territory. Thus, after a collapse of the government, fighting over territory would continue between the Houthis on one side, and the STC, the Joint Forces and other armed groups on the other. In late 2021, the Houthis were already able to take parts of Shabwa, sparking fears that the rebels could push further into resource-rich Hadhramaut. They will certainly try to capture the city of Taiz, which they have already besieged.

Initially, an offensive by the Houthis from the north would unite their opponents. In the medium and long-term, however, further fragmentation of the anti-Houthi alliance would be expected. In Taiz, for example, the UAE-backed Joint Forces already began gradually infiltrating the city in 2019 to counter the dominance of the Islah Party. While the Joint Forces are still loyal to Hadi today, in the event of a government defeat in Marib, they would align themselves more closely with the UAE, which could lead to open conflict with the Islah Party. Moreover, Tareq Saleh might be tempted to assume positions held by the Hadi government, which in turn could lead to conflict with the STC. Finally, given that the UAE has vested interests in the south, Houthi advances into southern territory could lead to increased Emirati military engagement and continued cross-border attacks. The January 2022 Houthi-claimed drone attacks on Abu Dhabi were also provoked by the current coalition’s victories, and are meant to remind the Emirates of what is at stake if they challenge Houthi control.

Scenario 3: Negotiated Division of the Country, with Marib as a Bargaining Chip

In this scenario, the Houthis would negotiate directly with the regional powers on a solution that would maintain the status quo and divide the country into a northern part and one or more southern parts. Here, a key role would be played by the UAE, which is interested in maintaining its influence in southern Yemen. The Emirates already exert de facto control over the port of Aden, the strait of Bab al-Mandab and the island of Socotra off the Horn of Africa. At the same time, they can use their local partners to weaken the Islah Party, potentially even supporting groups loyal to them in taking over positions previously held by the Islah Party. This would not only weaken the Hadi government, contributing to its gradual collapse, but also set the stage for direct talks.

After the UAE was made aware of its own vulnerability in 2019 when oil tankers were attacked in its territorial waters, it set its sights on easing its relationship with Tehran. As a confidence-building measure, it gradually withdrew its troops from Yemen, especially from the region around the port of Hodeidah. This strategically important city was then completely captured by the Houthis in November 2021. To avoid further cross-border attacks, the UAE would need to stop challenging the Houthis militarily.

However, in order to permanently maintain its spheres of influence in southern Yemen, the UAE would need to contain the Houthis in the north through a mixture of military force and negotiations. In this scenario, the Saudi government subordinates its military and diplomatic actions to the UAE, as it has so far been unable to assert its interests with its own strategy. The December 2021 success in Shabwa was a rare show of unity of the anti-Houthi alliance: UAE-supported forces, with Saudi air support, launched an offensive against the Houthis, making up for lost ground and making an advance towards Marib possible. While the UAE has in the past demonstrated little interest in Marib, securing the oil-rich city from the Houthi offensive could allow the UAE not only to assume a stronger position in potential talks, but also weaken the Islah Party in the city.

In this scenario, peace talks are likely to tie in with the direct negotiations between the two Gulf monarchies and the Houthis which were facilitated by Oman in the past. Unlike the UN peace process, this parallel track seriously considered the network of interests and the balance of power of local and regional actors. However, curbing Houthis’ military ambitions through negotiations has proven difficult, and both Saudi Arabia and the UAE will need to gain leverage over the rebels for talks to be successful.

While the Gulf States would need to accept Houthi rule in northern Yemen, they would in return require guarantees that put an end to any further military advance within Yemen’s borders or cross-border missile or ground attacks. Additionally, Saudi Arabia is likely to insist on a buffer zone along its border with Yemen. Such guarantees would require both Iran’s constructive influence on the Houthis and an agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. However, this can only be expected in the medium-term if the Gulf States continue to influence the government in Tehran with confidence-building measures and if the international nuclear talks with Iran are productive. The Houthis, for their part, would demand an end to the air, land and sea blockade; they could also demand the right to export oil, as this is essential for the economic survival of northern Yemen. For this, the Houthis would require access to the oil fields in Marib. The city of 2 million may well serve as a bargaining chip in such talks. Enabling the economic survival of the Houthi territory may be the only leverage the Gulf States have over the rebels.

However, negotiations between the Gulf monarchies and the Houthis can only really end the regional dimension of the conflict. Locally, the talks could only preserve the status quo. While the Houthis may hope to be recognised as representatives of the entire Yemeni people, the STC claims the entire territory of the formerly independent South Yemeni state. The UAE would need to allow local actors in southern and western Yemen to resolve their tensions before possible negotiations. The STC would need to be thwarted and groups that do not feel represented by it would have to be involved in talks. This is also true for the Joint Forces, with their sub-groups, and for representatives of the provinces of Hadhramaut and Mahrah. The stability of the country therefore depends not only on the actions of the Houthis, but also on a political consensus of the remaining anti-Houthi alliance.

Conclusion

While the Hadi government might hold the city of Marib for a few more months or even years, it is difficult to imagine a shift in the military balance in favour of the Hadi government significant enough to lead to meaningful negotiations. Whether the third scenario occurs and an end to the regional dimension of the conflict can be initiated depends on whether the regional powers Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran engage constructively. A stable political order can only emerge in Yemen if the impact of the regional disputes on the internal political dynamics is minimised and a pragmatic, purposeful and inclusive dialogue is initiated, involving not only the Yemeni parties to the conflict but also women and civil society. Against this backdrop, Germany and its European partners should continue to support the rapprochement of Saudi Arabia and Iran to facilitate a negotiated solution for both the regional and local dimensions of the conflict. Close cooperation should be sought with Oman, as Muscat maintains good relations with both countries.

Within the UN mission, Berlin and Brussels should promote a more flexible approach to the negotiations. Especially in case of a collapse of the Hadi government and subsequent direct talks between the Houthis and the Gulf states, the UN should continue to advocate for an inclusive solution and political dialogue within Yemen. In order to support the UN in this, Europeans should engage the UAE and Iran to exert a moderating influence on their local allies. The German government should not make any concrete concessions to the Houthis – e.g., recognise them under international law – until the rebels have demonstrated that they too will abide by agreements.

Human rights violations by all local and regional parties to the conflict should be condemned in the strongest possible terms. With the new armed groups in power in Yemen and their supporters in the region, civil and human rights will continue to erode. Women’s rights in particular have been severely disregarded by all parties to the conflict. The Houthis are cracking down on opposition figures, journalists and academics. They are being arrested or abducted, publicly executed or simply murdered. In the south, the STC propagates a nationalist discourse that repeatedly leads to violence against northern Yemenis. The Arab coalition frequently targets civilians and civilian infrastructure. Most recently, in January 2022, they struck a detention centre, killing nearly 100 adult and child migrants. At the international level, Germany should therefore support the initiative of the Dutch government to resume the reporting of the Expert Group on Yemen at the UN Human Rights Council.

In order to establish an inclusive political dialogue in Yemen in the long-term, Germany and its European partners should help the parties to the conflict and Yemeni civil society to develop new political visions for one or more Yemeni states. A broad discussion on how Yemen could be politically reordered has not yet taken place. This is absolutely necessary so that ideas about a new inclusive political order can flow into negotiations. The networks of the Berghof Foundation (Berlin) and the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (Geneva) could be used for this purpose. Equally important would be a poll-based debate in the Yemeni media on the future of the country.

If peace is to last, much work is necessary, particularly at the local level. Due to the fragmentation of the nation-state, a significant amount of responsibility already lies with the local authorities; this responsibility will increase even more following a collapse of the government. Accordingly, Germany should definitely strengthen its relations with local administrations within the framework of stabilisation and development cooperation to support them in the provision of public services.

Mareike Transfeld is a doctoral student at the Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies at Freie Universität Berlin and co-founder of the Yemen Policy Center Germany. Between 2014 and 2015 she was an Associate at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2022

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

doi: 10.18449/2022C06

(Revised and updated English version of SWP‑Aktuell 3/2022)