The International Dimension of European Climate Policy

A Strategy for Integrating the Internal and External Dimensions

SWP Comment 2025/C 03, 20.01.2025, 7 Seitendoi:10.18449/2025C03

ForschungsgebieteWith the Green Deal, the European Union (EU) has not only significantly increased the ambition of its climate policy in recent years, but it has also added an international dimension to European domestic climate policy. In fact, numerous recently adopted legal acts directly or indirectly affect international partners. Nevertheless, the internal and external dimensions of climate policy are not systematically interlinked in the new European Commission, and there is little strategic diplomatic support for the measures. In view of the increased importance of competitiveness and geopolitical constellations, there is an opportunity for a new strategy process. This could help EU institutions and member states coordinate the external dimension and achieve a meaningful advancement of European climate policy.

With the new European Commission having taken office in December 2024, concrete preparations for the next phase of EU climate policy are gathering pace. Since incoming US President Donald Trump will most likely reverse many of the Biden administration’s climate policy initiatives, expectations are once again focussed on the EU’s course in this area. However, over the past years, the climate policy landscape has also changed significantly on this side of the Atlantic. After the European elections in 2019, then new Commission President Ursula von der Leyen initiated the European Green Deal 100 days after taking office by passing the “European Climate

Law” (Regulation 2021/1119). In addition to substantial increases in legally binding emission reduction targets for 2030 and 2050, further developments to the existing governance architecture were also agreed during the last legislative period, despite major crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, the implementation of the Green Deal, which requires the support of member states as well as the Commission, is still to come. It is now taking place in a political environment that has fundamentally changed and offers fewer opportunities for ambitious climate policy.

Integrating climate policy and competitiveness

One reason is the crisis in Europe’s industry and its competitiveness, topics that have become the focus of political debate following the report by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi in September 2024. Commission President von der Leyen announced that she would present a Clean Industrial Deal within the first 100 days of her new term as part of her endeavour to buttress the progress in climate policy of the past five years with industrial policy. In addition to von der Leyen’s programme, the composition of her College of Commissioners signals that economic security, competitiveness and strategic autonomy will shape the EU’s agenda until the next elections in 2029. The new division of responsibilities is a clear attempt to link climate policy more closely with competitiveness.

Spanish social democrat Teresa Ribera’s area of responsibility illustrates the attempt to fuse climate protection and competitiveness. As the first Executive Vice-President of the Commission and head of the influential Directorate-General (DG) for Competition, she is responsible for the portfolio promoting a clean, just and competitive transition. She will be working closely with French Liberal Stéphane Séjourné, who is Executive Vice-President for Prosperity and Industrial Strategy and Head of DG Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises). At the level of subordinate Commissioners, Wopke Hoekstra (Netherlands, European People’s Party – EPP) in DG Climate Action; Jessika Roswall (Sweden, EPP) in DG Environment; Dan Jørgensen (Denmark, Socialists & Democrats – S&D) in DG Energy; and Maroš Šefčovič (Slovakia, S&D) in DG Trade will be responsible for key interfaces in the new Commission for climate policy developments.

Thus, each of the three major political parties (EPP, S&D, Renew) are leading important climate-relevant portfolios to ensure balance and cooperation between them. However, the intense debates in the European Parliament during the hearings of the designated Commissioners indicated that – as in the previous term – the composition of responsibilities roughly outlines the actual influence of individual DGs and Commissioners, while controversial issues are deliberately kept open and subject to overlapping responsibilities. Both the lack of clear prioritisation and the structural diffusion of responsibilities are likely to complicate rather than help manage conflicts in this legislative-laden policy area.

Tensions between domestic and foreign climate policy

The Commission’s division of labour does not take the tensions between the internal and external dimensions of climate policy sufficiently into account, despite the fact that several instruments adopted as part of the Green Deal have had significant impacts on international partners and are already causing diplomatic upheavals. The external dimension of European climate policy only appears on the margins of the mandate of the new High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Kaja Kallas (Estonia, Renew), who, as Vice-President of the Commission, also heads DG International Partnerships (INTPA). Von der Leyen’s political guidelines also do not address this interface strategically or institutionally. The central challenge is therefore not only the much-discussed relationship between the portfolios for energy and climate policy (Ribera) and industrial and trade policy (Séjourné), but also their respective relationship to foreign and development policy (Kallas). A key field of action for ambitious climate policy remains up in the air. Tackling it would require more coordination, especially with regard to new industrial and trade policy measures.

International dimension of the European Green Deal

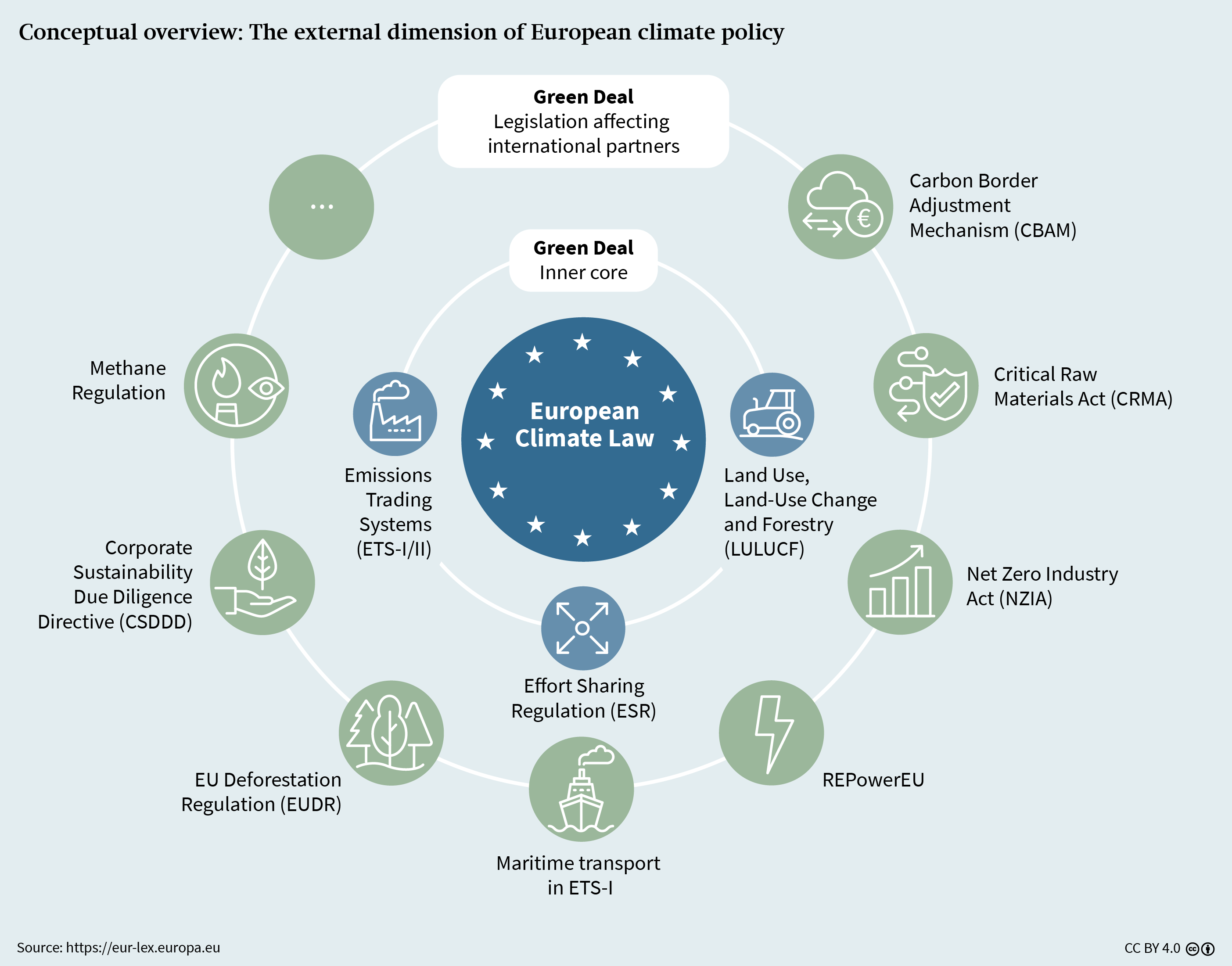

A number of legal acts of the Green Deal impact international partners. This international dimension should be conceptualised as part of EU climate policy, which is often presented as consisting of three pillars – firstly the Emissions Trading System (ETS) I; secondly the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) and ETS II; and thirdly land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). As a conceptual overview, Figure 1 shows the European Climate Law and the three pillars as the inner core of European climate policy. An outer ring consists of selected legal acts from the Green Deal that contain obligations for member states but also have an impact on trading partners outside the EU’s internal market (for a brief explanation of the selected legal acts, see Table 1).

Impact on partner countries

All of the legal acts listed in Figure 1 result in direct or indirect costs and obligations for non-EU countries. They can be divided into three groups. In the first case, levies are imposed on imports, or these imports are made more expensive through higher standards in order to level the playing field. These include, among others, the integration of shipping into the ETS and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). A second group of measures seeks to improve competitiveness within the EU through greater resilience. To this end, policies focus on greater independence from energy imports (REPowerEU) and on targets for the production of strategically important technologies to achieve the EU’s net-zero target (Net Zero Industry Act, NZIA). A third category of measures does not entail any direct costs, but involves documentation obligations that are intended to establish the objectives of the Green Deal for international supply chains. These include the European Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

Implications for the EU

Depending on the consequences of the legal acts for non-member states, implications for the EU itself differ. Three aspects can be distinguished. Firstly, increasing international resistance – such as from Brazil in the case of the EU Deforestation Regulation – is already making it more difficult to shape or implement the aforementioned legal acts. The United States under a second Trump presidency could respond to methane regulation or the CBAM with asymmetric countermeasures.

Secondly, conditions for international climate cooperation are deteriorating. When economically poor countries are affected by the legal acts, trust in the EU as a climate leader and fair mediator in international formats risks being undermined. For example, Brussels has failed to make the CBAM compatible with the development interests of partner countries, either by exempting poorer countries or offsetting additional export costs through the targeted support of affected sectors.

Thirdly, the lack of strategic diplomatic support for the international dimension of the Green Deal threatens to weaken the EU’s foreign policy as a whole. Measures such as the CBAM and the EUDR are attracting significant criticism from large emerging economies such as Brazil, Indonesia and South Africa – the very countries that the EU wants to win over as partners in other policy areas in view of the geopolitical situation.

Internal barriers to the integration of domestic and foreign climate policy

The CBAM example clearly shows that the current institutional logic is not adequate. At the interface of European and international climate policy, unclear responsibilities, different internal EU objectives and ad hoc diplomacy are leading to enormous resistance in partner countries.

Within the Commission, a large number of DGs are involved in EU climate diplomacy. Key players are DG Climate Action, which conducts international climate negotiations and partnerships in addition to its domestic policy competencies; the European External Action Service (EEAS), which is responsible for coordinating the EU’s foreign policy activities; and DG INTPA, which plays a central role vis-à-vis developing countries and in the area of climate finance, with formats such as the Global Gateway (GG) initiative and the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs).

However, in view of the division of labour and von der Leyen’s “Mission Letter” to Kaja Kallas, it is also clear that climate diplomacy and EU foreign policy will continue to be conducted in separate spheres. This makes greater integration structurally more difficult. More coordination would be particularly important in light of the competencies of the EU – where foreign policy is primarily determined by member states, but climate policy is largely determined at the EU level. An additional challenge is posed by the inter-institutional position of the EEAS, whose role regarding the new economic foreign policy and issues of economic security remains unclear.

Beyond the DGs, other European institutions need to be more closely involved. This includes the European Parliament, which is a minor player on climate diplomacy but a major one on Green Deal legislation. Such an approach requires a political-strategic framework that sets out principles of cooperation as well as substantive goals. The conclusions of the Foreign Affairs Council, which annually define the EU’s energy and climate diplomacy priorities, are a first step in this direction.

|

Explanation of the legal acts |

|

|

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), CO2 border adjustment system |

CO2 border adjustment system for pricing CO2 in imported products (electricity, cement, steel, aluminium, fertilisers and hydrogen) with reporting and payment obligations for importers. |

|

Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), regulation on critical raw materials |

European Raw Materials Act with the aim of building up capacities and making internal and external supply chains more resilient, including through benchmarks, stress tests and partnerships. |

|

Regulation with the aim of covering at least 40 per cent of European demand from domestic production by 2030 with defined net-zero technologies. A global market share of 15 per cent is to be achieved by 2040. In addition, sustainability and resilience criteria in public tenders and a reduction in bureaucracy. |

|

|

Reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The aim is to end dependence on fossil fuels from Russia by diversifying supply, saving energy and accelerating the energy transition. The focus is on strengthening the EU’s strategic autonomy in the energy sector. |

|

|

Since 2024, the EU ETS has also included CO2 emissions from large ships with a gross tonnage of more than 5,000 (from 2026 also methane and nitrous oxide). For journeys to or from a destination outside the European Economic Area (EEA), 50 per cent of emissions are covered, and 100 per cent is covered for journeys within the EEA (gradual introduction by 2027). |

|

|

Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), European Supply Chain Directive |

The Directive aims to promote sustainable corporate behaviour domestically and in global value chains. To this end, adverse effects on human rights and the environment are to be reduced both within and outside Europe. Companies can be held liable for any damage caused. The rules apply in stages (2026–2029) for an increasing number of companies, depending on the number of employees and turnover within the EU. |

|

Since 2024, the new regulation has obliged the European gas, oil and coal industries to measure their methane emissions from the supply of fossil fuels, to quickly eliminate leaks and to reduce the venting and flaring of gases. Stricter requirements for imports are gradually being introduced. The aim is to ensure that monitoring, reporting and verification obligations equivalent to those of EU operators are gradually applied outside the EU. |

|

|

EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), Regulation on deforestation-free supply chains |

The regulation aims to ensure that certain goods placed on the market in the EU do not contribute to deforestation and forest degradation in the EU and elsewhere in the world. It covers palm oil, beef, soya, coffee, cocoa, wood and rubber as well as products made from these. Traders must prove that the products are deforestation-free. Implementation is suspended until the beginning of 2026. |

In practice, however, they rarely function as an actual basis for EU-wide action and do not solve coordination problems between the Commission’s DGs. In the absence of an overarching strategy, priorities resulting from the logic of individual institutions or DGs dominate. This sends contradictory signals to the EU’s partners about the external dimension of European climate policy.

A foreign policy flanking the European Green Deal

As the importance of European competitiveness has increased, there is now greater pressure to justify climate policy than there has been during the past five years. Strategically linking domestic and foreign climate policy provides two opportunities. Firstly, synergies between Green Deal measures and international competitiveness can be identified and driven forward through new initiatives. There is great potential here, especially for strategically important technologies and supply chains that are relevant in the transition to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. Secondly, a structured approach to the external dimension of European climate policy offers an important starting point to ensure that new instruments such as the CBAM do not primarily act as a source of tension for partners, but serve as components of new alliances by being diplomatically supported and embedded in broader initiatives.

Foreign policy instruments

The EU has a wide range of instruments at its disposal that could be utilised more effectively to support European climate policy diplomatically by aligning them more consistently with legal acts that have already been adopted under the Green Deal. New instruments should be designed accordingly from the outset.

The Global Gateway initiative, for example, already aims to combine the EU’s increasing focus on competitiveness and strategic interests with a commitment to cooperate with international partners. However, compared to other infrastructure projects, such as the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, the initiative’s announced budget of €300 billion by 2027 is small and lacks new and additional funds. In general, the initiative is characterised by fragmentation and a lack of strategy, and there are doubts as to whether Brussels’ guarantees can actually attract private investment levels that even remotely approach the envisaged amount of €135 billion.

Together with the announced Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships (CTIP), a strengthened GG initiative could renew the damaged trust in the EU as a climate leader and fair mediator. To achieve this, the initiative would have to bring together disparate EU interests in the areas of trade and investment with development and climate goals. This would not only require greater consideration of the priorities of partner countries, but also improved coordination between the involved EU institutions, member states and financial institutions. Particularly in view of the Commission’s stronger focus on competition policy, both instruments could be used more strategically, for example to reduce resistance to the CBAM and the EUDR. The CTIP should strive to make a comprehensive and clear offer to selected countries that integrates existing initiatives.

Country-specific approaches are desirable here, but they would be difficult in light of the diverse alliances of EU member states with partner countries and often strongly divergent interests, for example with regard to China. As a result, partner countries are often sceptical of the added value of cooperation with the EU and prefer bilateral cooperation formats with individual member states. The members of the Group of Friends for an Ambitious EU Climate Diplomacy, including Germany, should clearly analyse existing conflicts of interest, minimise differences and ensure that the respective cooperation formats of EU member states are given greater consideration than in the past.

EU internal cooperation

As neither the Global Gateway initiative (for which DG INTPA is responsible) nor the CTIP (DG TRADE) fall into Commissioner Ribera’s cluster, cooperation across DGs and a clear distribution of competences are necessary, following the example of the Team Europe initiative. Greater involvement and proactive engagement of EEAS delegations in selected partner countries can support coordination.

As a first step, von der Leyen’s “Mission Letter” has given Ribera the mandate to develop a “vision for climate and energy diplomacy” that should centre on foreign policy support for the European Green Deal. It could also be used as an impetus for a series of informal inter-Green Deal cooperation formats at the working level in order to systematically navigate conflicting objectives within Ribera’s cluster. Building on this, the Commission should initiate a broader strategy process, using experience from Germany’s “climate foreign policy” strategy as a reference and source of ideas. The newly created task force on international carbon pricing and carbon market diplomacy following the 2040 target recommendation could, in turn, be the starting point for another task force with a broader mandate. This process should involve all EU institutions and governments of the member states. To implement the strategy, the Commission could set up a high-level coordinating body, similar to the German format at the state secretaries’ level for climate foreign policy.

A cross-committee working group could be formed in the European Parliament, consisting of representatives from the Committees on Foreign Affairs (AFET), Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI), Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE) and International Trade (INTA). This could function as a platform for dialogue and new initiatives with regard to the foreign policy dimension of European climate policy.

Finally, it will prove important to create a regular overview of member states’ foreign climate policy activities and examine them for synergies and any contradictory activities and political priorities. This requires clear responsibilities and structured cooperation on climate diplomacy between the Foreign Affairs, Competitiveness, Environment and, where appropriate, Transport, Telecommunications and Energy Council configurations. It would also be conceivable to add a foreign climate policy dimension to the national energy and climate plans, which should be regularly updated. They could thus be used as a monitoring instrument and starting point for cooperation between the member states and trigger European and national initiatives.

The new Commission should take the first steps towards realising these proposals as soon as possible and in the context of the Clean Industrial Deal, which was promised for the first 100 days after taking office. The 2040 target and the subsequent legislative package for the continuation of climate policy after 2030 also offer opportunities for implementation, as does the EU’s national climate contribution to the Paris Agreement.

Ole Adolphsen is an Associate in the Global Issues Research Division and in the project “Climate Foreign Policy and Multi-level Governance”. Jule Könneke is an Associate in the Global Issues Research Division and Head of the project “German Climate Diplomacy in the Context of the European Green Deal”. Dr Felix Schenuit is an Associate in the EU / Europe Research Division and in the “Upscaling of Carbon Dioxide Removal (UPTAKE)” project. All authors are members of the Climate Policy and Politics Research Cluster.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C03

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 67/2024)