Focus on the Customer rather than Competitor: “Going the Extra Mile”

How can the EU and its Member States differentiate themselves if they cannot offer an excellent product, a particularly low price, or fast delivery? In these circumstances, there is a strong business case for focusing on "customer orientation", such as putting demand at the centre of strategic considerations.

Focusing on the priorities of African countries should not be seen as an end in itself derived from development policy principles. Rather, it is a promising strategy to generate a competitive advantage aimed at improving the long-term prospect for cooperation – economically and politically. To this end, it is important to demonstrate a stronger customer orientation than that of the competition. Despite the EU's commitment to a change in perspective towards equal relations with Africa, there is still a lot of room for improvement in this respect, also with regard to the Global Gateway.

Key concerns of African countries, such as better integration into global value chains, correcting the distribution of vaccines during pandemics, reforms in agricultural trade, better credit conditions, debt rescheduling in cases of hardship, and stronger representation of Africa in multilateral organisations can play a key role here. European actors should now make strategic decisions on the areas where they can act as credible and visible first movers – not in the sense of innovation (proposals for such measures have in most cases been on the table for some time), but in the literal sense of who moves first.

European actors can improve their reputation in the eyes of African actors by "going the extra mile", namely by accommodating Africa on substantive issues that are connected to costs and where changes are not easily reversible. This is perhaps most feasible at present in the area of climate finance ("loss and damage"), where substantial resources can be mobilized and the "pie can be expanded".

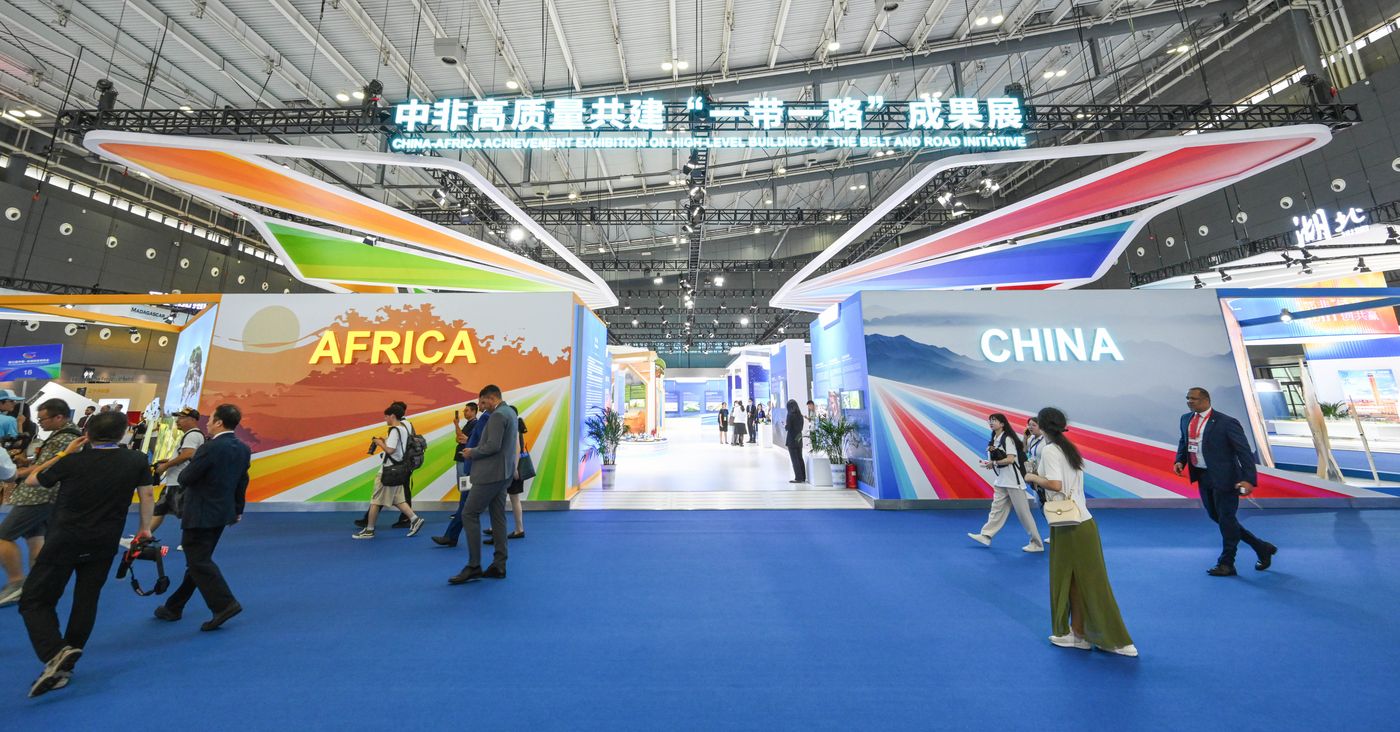

However, the window of opportunity to generate competitive advantage through such approaches is closing already. Beijing is also focusing increasingly on economic and political cooperation with the Global South, not least in view of US and European de-risking measures. Announcements to this effect are expected this week at FOCAC.