The Covid-19 pandemic has moved relations with Sub-Saharan Africa further up the Maghreb countries’ agenda and consolidated existing trends. Morocco is the Maghreb state with the most sophisticated Sub-Sahara policy. Its motivations include attractive growth markets in Africa, frustration over restricted access to Europe, stalemated integration in the Maghreb and the wish to see the Western Sahara recognised as Moroccan. Morocco’s Sub-Sahara policy has heightened tensions with Algeria and awakened ambitions in Tunisia. Algiers, as a significant funder and security actor in the African Union (AU) and “protector” of the Western Sahara independence movement, is seeking to thwart Rabat’s advances. Tunis for its part is trying to follow in Rabat’s footsteps, hoping that closer relations with Africa will boost economic growth. The European Union should treat these trends as an opportunity for African integration and triangular EU/Maghreb/Sub-Sahara cooperation. This could counteract Algeria’s feeling of growing irrelevance, strengthen Tunisia’s economy, put Morocco’s hegemonic ambitions in perspective, and thus mitigate the negative dynamics of the rivalry.

The Africa policies of the Maghreb states differ significantly in their intensity, visibility, motivations, and priorities. On a broader level they reflect each state’s general domestic and foreign policy capacities. This is visible not least in the way the countries market their Africa policies.

For some time Morocco has had the most dynamic and progressive Africa policy of the three countries. King Hassan II, who ruled from 1961 to 1999, had already put out feelers to West Africa. But it is under his son Mohammed VI (since 1999) that Morocco has proactively pursued a key economic and diplomatic role in Africa. Mohammed VI took personal charge of the country’s Africa policy, backing it with intense travel diplomacy and strategic appearances, for example at the 5th AU-EU Summit in 2017 in Abidjan. Rabat has achieved notable successes with its soft power approach, which encompasses economic, development cooperation, migration and religious components. In January 2017 Morocco was readmitted to the AU after 33 years, against the objections of heavyweights like South Africa and Algeria but strongly supported by numerous West African states as well as Rwanda. Morocco quit the AU’s predecessor in protest in 1984 after it accepted the Western Sahara into membership.

Morocco has enormously expanded its presence in Sub-Saharan Africa in the past decade, above all economically. It is one of the continent’s largest African investors, alongside South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria, and the biggest African investor in West Africa, where Moroccan insurance companies, telecommunications providers, and banks enjoy significant market shares. Morocco also exports agricultural and renewable energy technology, especially to West Africa, and is increasingly looking to East and Central Africa too, for example Ethiopia, Rwanda and Cameroon. Since 2017 Rabat has also been seeking accession to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), to date without success.

One central driver of this policy is the desire to open up new markets for Moroccan businesses, especially those controlled by the royal family. Two relevant aspects here are the limited access to the European Single Market and marginal economic interaction across the closed border with Algeria. Morocco’s desire for recognition of its claim to the Western Sahara is at least as important for its “turn to Africa”. Related to this is the regional rivalry with Algeria that goes beyond the Western Sahara question, where Algeria functions as the “protector” of the independence movement, the Polisario. Both states are seeking to exploit new opportunities created by changes in the larger regional context, such as the ousting of the Libyan leader and advocate of greater African unity Mu’ammar al‑Qadhafi, who played an extremely active role in African diplomacy, development, and security questions.

Neighbour Algeria Irritated

Morocco’s rise on the continent could be described as close to traumatic for Algeria, whose influence has waned substantially. During the first decades after independence in 1962 Algeria enjoyed great prestige in large parts of Sub-Saharan Africa on account of its military, logistical and financial support for anti-colonial movements. Close development cooperation with the newly independent African states and significant engagement in the Non-Aligned Movement also boosted Algeria’s standing across the continent.

Since its civil war in the 1990s, which coincided with the end of the Cold War order, Algiers has failed to restore its lost grandeur and its policy of “strategic depth” in Africa. The security sphere represents a partial exception. Here Algeria plays a relevant role within the AU institutions, and Algiers has also engaged as a mediator in African conflicts with some success. Economic initiatives under President Abdelaziz Bouteflika between 1999 and 2019 – such as an ambitious investment conference in Algiers at the end of 2016 – have been less successful. Although Algeria was a founding member of the AU’s development agency NEPAD (now AUDA), its engagement has remained modest, despite having had considerable material resources at its disposal until a few years ago.

From 2013, Algeria’s engagement in Africa was hampered by Bouteflika’s severe health problems, which ended his travelling diplomacy. Yet even before that, the Algerian President had shown waning interest in Africa, despite having belonged decades ago to the architects of Algeria’s early foreign policy and its support for anti-colonial movements.

His successor Abdelmadjid Tebboune, in office since December 2019, announced Algeria’s “return to Africa” at his first AU Summit in February 2020. While this is probably motivated by a desire not to leave the field entirely to Morocco, external security challenges also lead Algiers to look to the south: instability in Mali, chaos in Libya, pressure of migration on its southern borders, and the European and US military presence in the Sahel. The latter Algiers observes with suspicion.

However a contoured Africa strategy comparable to Morocco’s is not currently observable. And the prospects of one emerging are not especially good. Algerian decision-makers are preoccupied with significant internal and economic challenges – for which they have to date been unable to present strategies.

Tunisia Seeking to Catch Up

Tunisia has been observing Morocco’s Africa policy increasingly closely and enviously. In ministries and business circles one hears that Tunisia could in fact offer comparable or better expertise, for example in the IT, real estate development, and banking sectors, in technical planning of major infrastructure projects, and in health and education services.

After a good two decades where Sub-Saharan Africa played a marginal role, Tunisia has been gradually awakening from its slumber. Following the removal of the Ben Ali regime in 2011 the transitional government attempted to revive the African diplomatic engagement of the era of President Habib Bourguiba (1957–1987). But this was a brief episode of little strategic import. For example Tunis was unable to prevent the decision of the African Development Bank in 2013 to move its headquarters back to Abidjan.

Tunisia has nevertheless incrementally expanded its engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa, as demonstrated by its joining ECOWAS in 2017 as an observer, and its accession to the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) in 2018. In 2017 the then prime minister, Youssef Chahed, visited Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso. The new prime minister appointed in autumn 2020, Hichem Mechichi, announced that he would step up economic diplomacy in Africa. The country’s president, Kaïs Saïed, to date has shown only limited interest in Sub-Saharan Africa.

So far it is the private sector that presses hardest for a clearer orientation on Africa, first and foremost the Tunisia-Africa Business Council (TABC). It establishes contacts, organises conferences, and lobbies for the legal and administrative reforms required to encourage investment and exports. Given the fundamental problems of the young democracy – slow decision-making, an overwhelmed parliament, and a lack of political continuity – this is inevitably a protracted process.

Institutional Power Play

Morocco’s confidence, Algeria’s defence of its legacy and Tunisia’s reawakening interest are also reflected within the African institutions and organisations. The demise of Libyan dictator Qadhafi in 2011 made Algeria the unchallenged Maghreb heavyweight within the AU. But Morocco now contributes at least as much financially and expects relevant positions and influence in AU organs.

For almost two decades an Algerian has held the post of AU Commissioner for Peace and Security, who also oversees the AU’s Peace and Security Council (PSC). Morocco joined the PSC in 2018 and held its rotating chair in 2019. Where Rabat is represented in AU bodies there is often conflict over formulations that (could potentially) relate to the Western Sahara conflict, and over the presence of the Sahrawi Republic as a member of the AU. Although Morocco has not to date succeeded in excluding the Polisario from the AU, the fronts have hardened. Influential countries like South Africa maintain their unequivocal backing for the Polisario, but thirteen AU members explicitly support Morocco’s claim to the Western Sahara, having opened consulates in the Moroccan-occupied part since 2019.

Algeria is home to an important AU institution, the African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT). Morocco and Tunisia now have their own too: The African Migration Observatory founded in 2018 is based in Rabat, the AU Institute for Statistics in Tunis. In 2020 Morocco also achieved a minor victory in relation to African representation in the United Nations, providing the chair of the UN Human Rights Council’s Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Libya. Algeria’s candidate for the post of UN Special Representative in Libya was apparently rejected by Washington. This example illustrates how influence of the Maghreb states in Africa sometimes functions obliquely and/or relies on external backing.

Jostling over Security Alliances

Negative effects of the Algerian-Moroccan rivalry are especially obvious in the security domain. Algeria was one of the driving forces behind the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) through its engagement in the AU Peace and Security Council and the ACSRT. But despite pressing shared security challenges in the Sahel/Sahara region, none of the multilateral security initiatives includes all three Maghreb states – apart from loose involvement in Washington’s Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership. Instead Algeria and Morocco each attempt to make their own mark.

In 2010 Algiers set up a Joint Military Staff Committee (CEMOC) in Tamanrasset to fight terrorism in the Sahel with Mali, Mauritania and Niger and develop their security capacities. Morocco and Tunisia participate in the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), which was founded by Qadhafi and also has a security dimension. But neither CEN-SAD nor CEMOC play a significant role in the Sahel. Initiatives also involving international actors, such as the G5‑Sahel, are more visible.

Although Algeria has achieved successes in the field of conflict resolution, for example with the Accord d’Alger for Mali in 2015, Morocco has been challenging for that role. For example the Libyan Political Agreement establishing a UN-supported government was signed in Skhirat, Morocco, in 2015. In autumn 2020 the Libyan conflict parties again negotiated in Morocco, and later in Tunisia – despite Algeria repeatedly offering its services as mediator and enjoying the confidence of important conflict parties. What we see here yet again is the strong strategic and implementation capacity of the Moroccan monarchy. Even in Mali, where Algeria hoped to rapidly position itself as the mediator after the August 2020 coup, Morocco soon arrived to offer its services.

Tunisia seeks prominence principally in peace-keeping. In 2019 the Maghreb’s smallest nation participated in five UN missions in Sub-Saharan Africa, including MINUSMA in Mali. Morocco was involved in three missions in 2019, in two cases with large contingents. In November 2020 Algeria adopted a constitutional amendment permitting its armed forces to participate in international peace-keeping operations – most of which occur in Africa. This could trigger a Maghreb peace-keeping race, with potentially positive effects.

Unequal Economic Competition

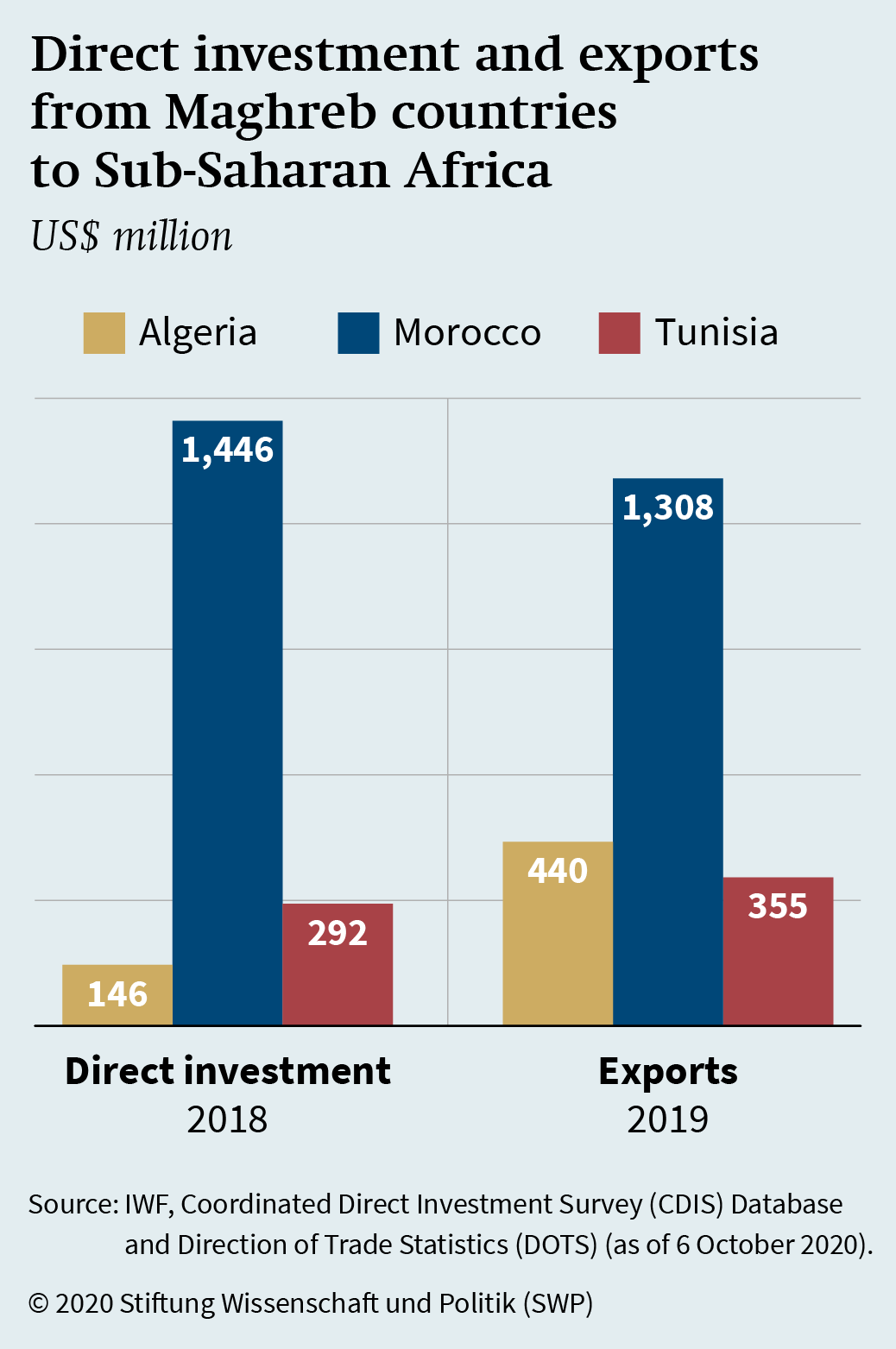

The sector where both Algeria and Tunisia have the most catching up to do is the economy. Casablanca is by volume the continent’s largest financial centre and Morocco is streets ahead in trade with and investment in Sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure).

Between 2005 and 2019 Morocco’s exports quadrupled and Tunisia’s more than doubled. Both have large trade surpluses with Sub-Saharan Africa. Algeria on the other hand imports considerably more from Sub-Saharan Africa than it exports there. Its export volume has however been increasing noticeably for some years and its imports from southern Africa have soared. This indicates growing trade relations with certain Sub-Saharan economies.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) launched in 2019 includes all three Maghreb states. It is designed to come into effect incrementally, and is initially unlikely to alter the imbalance towards Morocco. Tunisia and Algeria have no economic strategy for Sub-Saharan Africa (yet). Further hurdles are foreign exchange controls and the lack of double taxation agreements. Algeria also suffers a lack of diversification in its export sector and uncompetitive services; it remains to be seen whether government ideas such as offering services from its public construction sector to Sub-Saharan Africa states will be implemented and find demand. Tunisia for its part has undertaken first concrete steps, such as opening two new embassies and four trade offices in Africa.

Connectivity Is Key

Both Algeria and Tunisia have recognised that Morocco’s economic success in Sub-Saharan Africa has been boosted by a forward-looking policy of connectivity. In response, Tunisia has established new air routes to Sub-Saharan Africa and Algeria has opened a border crossing to Mauritania. Algiers lauded the latter as a step towards intensification of cooperation with West Africa as a whole. In 2020 Algeria also completed its section of the Trans-Sahara Highway, which is planned to eventually reach Nigeria; Tunisia is also connected. Whether this route – if its Sahel stretch is completed one day – can become a major transport artery will depend crucially on stability and security in the Sahel/Sahara region.

Morocco’s transport connections to Sub-Saharan Africa are likely to remain unrivalled in the longer term, if only by virtue of the country’s geographical location. Casablanca is far and away the Maghreb’s largest flight hub and Tanger Med has established itself as Africa’s largest port in terms of container shipping volumes, benefitting from its location where the Atlantic meets the Mediterranean. Sea routes from Algeria to Sub-Saharan Africa are long, from Tunisia even longer. Tunisia suffers an additional disadvantage in that all its land routes pass through Libyan or Algerian territory, making exports either dangerous or dependent on Algerian cooperation. For Tunisia’s export capacity to the south it will be vital to expand air transport – and its ports, despite the comparatively long sea routes. Yet, Moroccan connectivity also has its Achilles heel: its only land route to Sub-Saharan Africa runs through Western Saharan territory, making it vulnerable to conflict related blockages or even direct confrontation between Morocco and the Polisario, as was the case in November 2020.

Rivalries also exist in relation to energy infrastructure. Plans for a trans-Saharan gas pipeline from Nigeria to Algeria have been around for decades. An agreement for a pipeline from Nigeria via Morocco to Spain signed in 2016 appears to have better prospects of realisation.

The progress of such infrastructure projects depends not least on support from non-African states. China is especially prominent and is discernibly thinking about trilateral cooperation with North and Sub-Saharan Africa. As such it influences the Maghreb competition for the role of “gateway to Africa”. To date Algeria has been Beijing’s so-called “comprehensive strategic partner” in the Maghreb. But more recently China has been turning increasingly to Morocco, for example as an automotive manufacturing and export base for Africa as a whole. Russia, as a traditional partner of Algeria, is also showing interest in Morocco for trilateral cooperation with Sub-Saharan Africa.

Winning Hearts and Minds

Tunisian and Algerian attempts to keep up with Morocco in the field of soft power are still modest, as reflected in their external communication. Algeria was unable to capitalise strongly on debt relief of – according to Algerian announcements – around three billion US dollars for fourteen African states between 2013 and 2018. By contrast Rabat managed to generate international visibility for its deliveries of protective equipment “made in Morocco” to Sub-Saharan Africa during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the substance as well as the representation, Morocco’s Sub-Sahara strategy also pursues a significantly more sophisticated approach. First of all, much more research on Africa is conducted in Morocco. King Hassan II founded an Institute of African Studies back in 1987; since then a growing number of Moroccan think-tanks have sprung up working on Sub-Saharan Africa and Morocco’s role there.

The strategy is also reflected in concrete policies. In development policy, for example, Rabat has a well-established South-South focus encompassing classical development aid such as water projects. Algeria is attempting to catch up: in spring 2020 President Tebboune announced the creation of a development agency for Africa. The Tunisian Agency for Technical Cooperation (ATCT) currently covers Africa with just one office in Mauritania, but is increasingly drawing on external support for its African activities, for example from the German Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA).

Morocco’s education policy is also unrivalled. In 2019 it hosted more than 17,000 students from Sub-Saharan Africa, about half of whom received Moroccan scholarships. Algeria opened an institute of the Pan-African University (PAU) in 2014 with German support, although its student numbers are relatively small. Comprehensive figures for African students in the country are not available. In Tunisia the number of students from African countries has almost halved, from 12,000 (2010) to 6,500 (2018)

In religious diplomacy, too, Morocco stands unchallenged. Rabat trains imams from about ten African states and makes frequent use of its Sufi orders to open doors. This applies especially to the Tijaniyya, which has millions of adherents in West Africa. Leaders of the Moroccan Tijaniyya have accompanied the king and business delegations to Sub-Saharan Africa, and when the Moroccan foreign minister visited Mali after the coup in 2020 he also met with the order’s local leader. While the tomb of the founder in Fez, Morocco, has become a place of pilgrimage for believers from across Sub-Saharan Africa, Algiers has failed to generate symbolic capital from his birthplace in Algeria.

Last but not least, Morocco has outplayed the other Maghreb states with its migration policy. Since 2014 it has granted temporary residence permits to tens of thousands of irregular migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, enabling access to the labour market and health and education systems. Even if this policy looks more convincing on paper than it is on the ground, it has earned Morocco goodwill in Sub-Saharan Africa and a better look than Algeria and Tunisia. Although Tunisia set a milestone in 2018 as the first Arab country to pass legislation against racism, its measures, like Algeria’s, often lack visibility. Morocco simply sells what it does better, both at home and abroad.

The Limits of Africa Policy

Quite aside from the competition between them, the African ambitions of the Maghreb states encounter constraints:

Firstly, the Africa policies of the respective governments are not supported by their societies, which generally look more to Europe and the Arab world. Morocco’s Africa policy is the king’s hobbyhorse but finds little resonance among the political parties. Civil society actors complain that big business linked to the monarchy profits most while trickle-down effects are absent. In Algeria too, indifference towards Sub-Saharan Africa predominates, with Africa policy dependent on a handful of elites from the independence movement, some civil society actors, and a few visionary entrepreneurs. Tunisia’s turn to the South is propagated primarily by dynamic private-sector elites.

At the other end of the equation Maghrebi ambitions also encounter resistance among the governments and populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. Widespread racism in the Maghreb – brought to light by growing migration from Sub-Saharan Africa – plays a role. Sub-Saharan Africans frequently experience discrimination and violence, including at the hands of the authorities. Since 2018 Mali and Niger have seen recurring demonstrations against Algeria’s ruthless deportation policy. The Maghreb states risk acquiring a reputation as the enforcers of European policies against irregular migration.

Rabat has experienced the limits of its Africa policy since 2017, with the West African states denying accession to ECOWAS over concerns about Morocco’s economic – and general – dominance. Across Sub-Saharan Africa there are fundamental doubts over the willingness of the Maghreb states to fully integrate – and be prepared to forgo special status, for instance in trade relations with Europe. Only one Moroccan has been officially ranked in the pool of candidates for the election of new AU Commissioners in 2021 (with little prospect of success) and no Algerians or Tunisians have pre-qualified. One factor here may be many AU members’ reservations about the Maghreb states.

Nevertheless, the Maghreb states are likely to profit from the growing desire to find African solutions for Africa. In light of the shutdowns and transport disruption associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, voices within Africa are increasingly calling for purely continental supply chains to be established to reduce dependence on external actors. Morocco especially appears determined to assume a central role and not simply leave Sub-Saharan Africa’s attractive markets to outside actors like China, Russia, Turkey, the Gulf and European states.

European Union: Promote Positive Dynamics

The EU’s policy towards the Maghreb has to date operated principally within the framework of its Neighbourhood and Mediterranean policies. Individual EU states, including Germany, also cooperate closely with individual Maghreb states. Growing interest in Sub-Saharan Africa in both the Maghreb and Europe opens up new perspectives for all sides. Realising them will require German and European economic and political actors to conceptualise their policies more strongly in terms of the continent as a whole, and specifically continental integration. They must not treat the Maghreb’s interest in Africa as competing with its interest in Europe or with Europe’s own interest in Africa. Appropriate starting points include the framework of the G20 Compact with Africa (CwA).

In the medium term African integration could function as the motor for the Maghreb integration process that the EU seeks to foster, to date unsuccessfully. Successful (economic) integration in Africa could also function to stabilise the Maghreb, which would clearly be in the EU’s interest.

For the EU, supporting such promising developments implies firstly a stronger focus on trilateral economic and development cooperation. Concretely this could mean employing and learning from Maghrebi expertise, for example in German and European economic partnerships and development projects with Sub-Saharan Africa. Here the Maghreb can help to build or expand financial and technological bridges between Europe and Africa.

It is therefore obvious, secondly, for experienced exporters like Germany to offer technical expertise to the two “stragglers” on matters such as developing strategies and expanding the infrastructure for exporting locally produced goods to Africa. This would also benefit German and European manufacturers producing in the Maghreb by opening up markets comprising about one billion consumers. A corresponding project for Tunisian small and medium-sized enterprises is already running, with funding from the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Trilateral cooperation can also mean jointly creating the preconditions for positioning Tunisia as an IT hub and health training centre for Africa; in both areas the country is a leader on the continent. It is also an opportune moment to offer Algeria support for exporting goods and expertise: Algiers is currently interested in export diversification and in rectifying its trade deficit with Africa. The government stands under great pressure to produce results.

Thirdly, European actors must work to minimise the potential negative (side-) effects of European policies in the Maghreb. Migration management must take into consideration the reputation of the Maghreb states, which is closely bound up with the treatment of migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa. It must also be ensured that the border management policies Europe pushes in Africa do not interfere with African integration. Europe should also take Africa’s efforts to develop the AfCFTA seriously: negotiations over bilateral free trade agreements with Morocco and Tunisia should pay heed to possible consequences for African integration.

Fourthly it is important to counteract Maghrebi zero-sum thinking. Rather than supporting the Africa policy of either Morocco or Algeria or Tunisia, the EU should support the constructive elements of each. This also applies to the Maghreb states’ engagement for peace and security in Sub-Saharan Africa. In relation to the Western Sahara Europe should continue to support the UN line and not subscribe to unilateral French or Spanish initiatives.

There is a great deal to gain geopolitically if Europe establishes itself as a dependable supporter of closer relations between North and Sub-Saharan Africa and forges ahead with triangular cooperation. This would slow the growth of openings for other external actors such as China, India, Turkey, and the Gulf states and strengthen the European-African axis.

Dr. Isabelle Werenfels is Senior Fellow in the Middle East and Africa Division.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2020

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN 1861-1761

doi: 10.18449/2020C54

Translation by Meredith Dale

(Updated English version of SWP‑Aktuell 83/2020)