Interlinking Germany’s Global Health Strategy at the European Level

An Analysis of Priorities and Coordination Potentials in EU Partner Countries

SWP Comment 2024/C 43, 17.09.2024, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2024C43

Research AreasThe German global health strategy review process offers the opportunity to place a stronger focus on the horizontal integration of Germany’s global health efforts with those of European partners. This is urgently needed as the German strategy makes little reference to the European Union (EU) and entirely excludes EU member states. However, Germany’s consideration of the strategic priorities of these actors would enable it to proceed in a united, coherent manner and to form new partnerships in specific policy areas. The systematic analysis of the strategies of other EU countries provides starting points for these considerations, as the identification of country-specific strategic priorities can shed light on opportunities for better linkages and coordination with the global health policies of other EU member states. Based on this, the partners that are particularly relevant for Germany in specific fields of action can be determined, and blind spots in German global health policy can be identified.

The review process for the Federal Government’s Global Health Strategy, published in October 2020, offers the opportunity to take stock and adjust its further implementation by 2030. In addition to evaluating the initiatives aimed at achieving the set goals, it is advisable to also consider the strategic priorities of other EU member states.

Since the publication of the German strategy, both the EU and a small group of member states have published their own strategies. Like Germany, these actors set their own priorities and define specific goals. It is noteworthy in this regard that all strategies make little reference to one another and largely consider their own role in global health – namely in combating diseases internationally, strengthening health systems and health equity, and fostering research and innovation – in isolation. The German document does not build a bridge to European partners and only mentions the EU in peripheral areas. The same applies to the strategies of other member states and the EU, which also do not reference other strategies and consistently address all member states together.

Although the EU, in addition to its own efforts, also serves as a platform for coordinating national health measures, there is a lack of approaches to assess priorities and better coordinate activities. However, this is urgently needed to prevent fragmentation and initiate strategic partnerships in specific fields of action. An analysis of the priorities laid down by the EU and its member states in their respective strategy documents provides insights into which countries are of interest to Germany as cooperation partners.

Consolidation of EU approaches

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU supported third countries in addressing health issues. This commitment, based on a broad definition of “global health”, is also understood as part of development cooperation. However, it goes beyond development aid and touches on various areas of the EU’s external action. When it comes to external action, the EU has significantly more room to manoeuvre than in its internal affairs, which are characterised by highly restricted health policy competences.

Driven by the pandemic, the EU’s various ambitions and approaches were first consolidated in November 2022 in its “Global Health Strategy”, which pursues three main goals: enhancing global health security, strengthening health systems, and promoting health and well-being. Health security includes preventing or rapidly containing threats such as pandemics and antimicrobial resistance in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO). Strengthening health systems involves ensuring universal coverage, improving infrastructure, and enhancing the training of professionals. Finally, the aim of promoting health and well-being is to combat inequalities, improve nutrition and mental health, and influence the socio-economic determinants of health in a positive manner. To implement the strategy, detailed action plans are to be developed, and regular evaluations are to be conducted. However, the “Global Health” document only mentions inter-ministerial meetings and coordination within the framework of the “Team Europe” approach.

Overall, the substantive added value of the EU for the member states lies in the extensive investments in health security and health systems, in technical support and crisis response capabilities, and in the economic and political influence that enables the pursuit of a “Health in All Policies” approach. However, the added value from the coordination of European approaches is not yet apparent. Generating this is even more important, as a cursory glance at the EU strategy is enough to realise that, due to its scope, it necessarily overlaps with the agendas of the member states, including Germany.

Germany’s global strategy

Germany’s commitment to global health is reflected in a long tradition of international initiatives, increasingly accompanied by concept papers. The 2020 strategy of the Federal Government defined five main goals: promoting health, addressing environmental and health issues together, strengthening health systems, addressing cross-border health threats, and promoting research and innovation.

Germany is committed to supporting WHO and advancing cooperation to improve global health governance. International health initiatives are to be strengthened to prevent and control pandemics and other health threats. This includes promoting the resilience of and accessibility to health systems, improving health infrastructures, and training health personnel. In all these measures, attention must also be paid to overcoming inequalities in the health sector. Research and innovation are to be advanced through support for the development of new medicines, vaccines, and technologies.

Regarding the instruments to implement these goals, the strategy mentions Germany’s involvement in international forums and networks, financial support for health initiatives, and a focus on policy coherence. The commitment to global solidarity and the universal human right to health is emphasised. In line with this, an integrated approach to addressing global health problems is pursued. It is noteworthy that the document assigns the EU a rather modest role, stating that it can set international (data protection) standards through “innovation-friendly regulations”. This contradicts the ambitions of the EU outlined above. Furthermore, Germany does not explicitly assign the EU the task of coordinating the actions of member states. The role of other EU members is not considered at all.

Strategies of other member states

While numerous EU member states have published guidelines for improving national health, only France, the Netherlands, and Sweden have published global health strategies.

The “Stratégie Française en Santé Mondiale” was presented at the end of 2023. It is entirely focused on “Universal Health Coverage” (UHC) and emphasises the fight against diseases and better anticipation of, prevention of, and responses to health crises. The document prioritises the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), overcoming inequalities, and addressing climate change. It is committed to the “One Health” approach and the protection of human rights and French values.

The Netherlands’ strategy, the “Nederlandse Mondiale Gezondheidsstrategie” of 2023, takes a slightly different approach by explicitly prioritising the strengthening of the global health architecture over other concerns. Pandemic preparedness and response, along with the health implications of climate change, are also high on the agenda in the Dutch document. However, it differs in its concrete priorities by focusing on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), antimicrobial resistance, sustainable health care, and access to medical countermeasures and supplies.

Sweden has adopted a completely different approach with its “Strategi för Sveriges samarbete med Världshälsoorganisationen (WHO)”. The concept, presented in 2021, explicitly views Sweden’s goals through the lens of its collaboration with WHO and outlines how the Swedish government should support the United Nations (UN) organisation in specific areas of activity. Other key aspects include achieving the SDGs, implementing UHC, improving the global health architecture, and broadly promoting healthy living. Even this brief overview shows how differently each country’s priorities are set.

Systematic text analysis

The systematic examination of the strategy documents utilises text analysis methods such as relative word frequency and the mentioning of specific topics. Employing statistical models, the author calculated the distances between the different strategies in terms of their content, provided a synthesis of key points, and identified similarities and differences in the texts.

Distances between the strategies

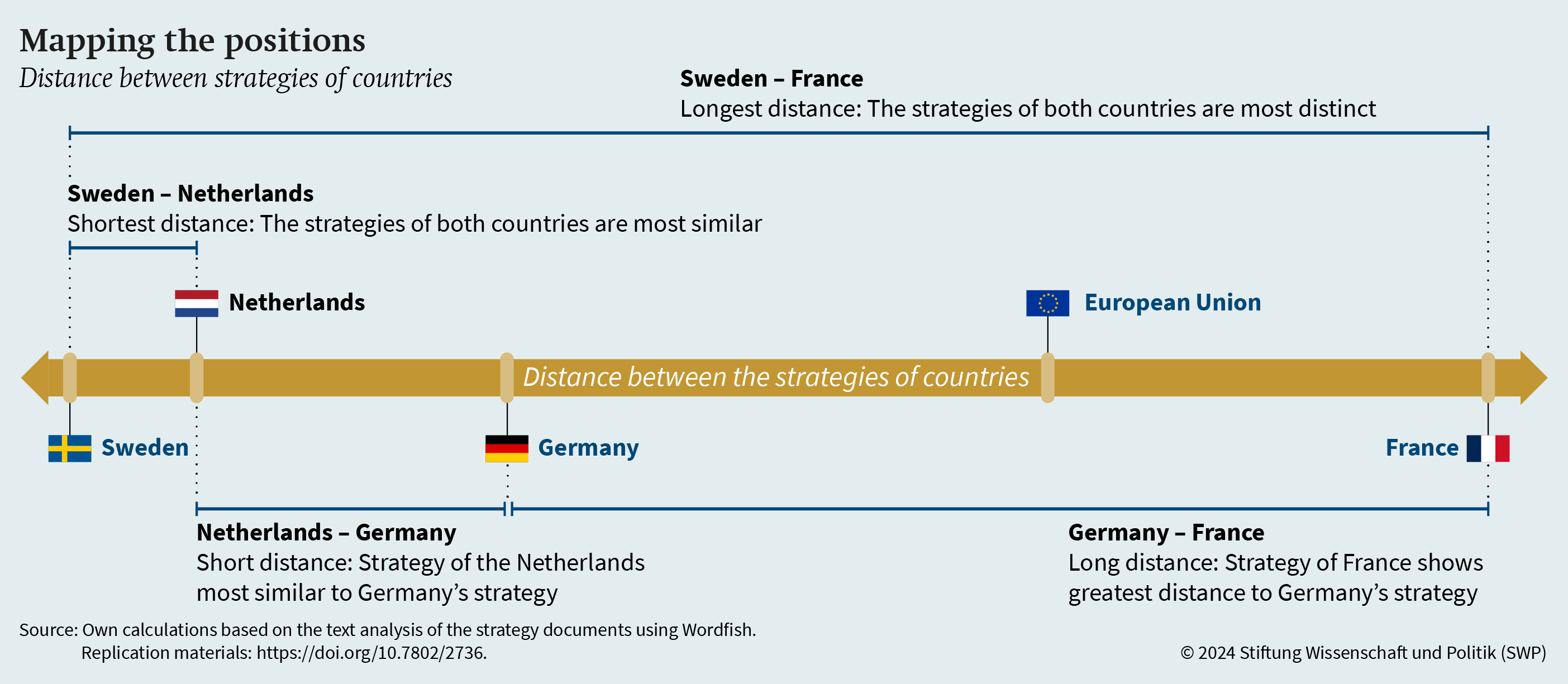

A first impression of the congruences and discrepancies between the individual strategies can be gained by determining the textual distances between the documents. Specifically, this is done based on an examination of word choice and word frequency. For this purpose, a model is used that quantifies differences in word usage and presents them graphically as a so-called latent dimension, in this case: alignment in global health policy. By estimating parameters for each document, the thematic position of the texts within this dimension can be determined. For this purpose, the actual parameter values are less relevant than the relative distances of the texts from one another, which are expressed by the parameters (see replication materials). The analysis thus goes beyond counting individual words and prioritising individual aspects and enables the positioning of all strategies on a continuum, which is illustrated in Graphic 1. The graphic reveals significant differences in the strategic positioning of the EU and its member states compared to Germany. The Dutch strategy shows the greatest proximity to the German strategy.

What is most surprising is the distance between Germany and both the EU and France. Even though synergies could still be identified in the above summary of the strategies, the systematic text analysis shows that both France and the EU view global health policy from different perspectives. This does not necessarily mean that the strategies are opposed to each other, but it does indicate that there is currently a lack of a common language and basic coherence of engagement. This is particularly true regarding the EU, in which Germany is a driving force in global health. Ultimately, however, the distance between the strategies also reflects different priorities.

Focus areas

The focus of the different strategies can by identified by relying on the occurrence of certain terms in the respective documents. In conducting the word frequency analysis, meaningless but recurrently occurring words (articles, pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.) are removed, as are terms such as the name of the respective country and other high frequency words that have little meaning in the context of global health strategies (e.g. “health”).

The results of the text analysis of the individual strategies are presented in Table 1, which lists the five most common words, including the interpretation from the context of their use. The table shows a substantial variance that was already noticeable in the initial analysis of the strategies and the mapping of the distances. Significant differences are revealed regarding the two most common words.

The German strategy stands out for its focus on research and development (“Research”) and health systems (“Systems”). The EU strategy is characterised by a more detailed discussion of cross-border health threats and pandemics (“Pandemic”) and an emphasis on development cooperation (“Partners”). In the French document, as in the German strategy, research and development (“Research”) hold a high value, leading to some overlaps. In addition, special attention is paid to the accessibility to medical services (“Access”), a term that does not appear among the top five in the German health strategy.

The Dutch and Swedish strategies differ from those previously discussed. The Netherlands places environmental aspects at the forefront of its guidelines by emphasising the “One Health” approach (“Climate”). Cross-border health threats are also prioritised here. Sweden has chosen a very different approach with its “Strategy for Sweden’s cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO)”. Presented in 2021, the concept explicitly views Sweden’s goals through the lens of WHO’s work and specifies how the UN organisation should be supported by the Swedish government in specific areas of activity. Further central aspects are achieving the SDGs, implementing UHC, improving the global health architecture, and promoting healthy living in the broadest sense. This brief overview already shows the variations in emphases.

Identification of synergies

|

Word frequency in global health strategies Marked words carry relevance |

||||||

|

Rank |

Germany |

EU |

France |

Netherlands |

Sweden |

|

|

1 |

Research |

Pandemic |

Access |

Climate |

WHO |

|

|

2 |

Systems |

Partners |

Research |

Pandemic |

Organisation |

|

|

3 |

Cooperation |

Systems |

National |

Water |

Agenda |

|

|

4 |

Organisation |

Team |

Healthcare |

Access |

Cooperation |

|

|

5 |

Climate |

Cooperation |

Systems |

Cooperation |

Rights |

|

While the examination of word frequency can already make the focus areas transparent, the identification of possible partners for Germany’s efforts in global health policy must be based on a more granular approach. The EU is not, strictly speaking, a partner of Germany and the member states. However, it sets its own priorities and creates the framework for German efforts, making it highly relevant to find synergies concerning the EU as well. To this end, 10 key points of German efforts are selected, and their status in other strategies is examined.

The results of this analysis are presented in Table 2, which lists the German key points, based on the strategy, and assigns a rank to the other strategies that corresponds to the prioritisation of the respective points in the other strategies. Cross-border health threats are given high importance in all the strategies analysed and have a particularly special status in the EU strategy. This was already evident when looking at word frequency and corresponds with the competencies of the EU in the protection against cross-border health threats.

References to the “One Health” approach, which links human and animal health with environmental aspects, and the “Planetary Health” concept, which takes the entire ecosystem into account, are also present in all strategies. The Netherlands engages intensively with both paradigms, making it a designated partner for Germany, which also emphasises the nexus between human and animal health, climate, and the environment. However, it is questionable whether the new government will continue to prioritise this focus.

|

Germany’s strategic priorities in other health strategies Ranking of other strategies according to prioritisation |

||||||

|

German priorities |

EU |

FR |

NL |

SE |

Top partner |

|

|

Cross-border health threats |

1 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

EU |

|

|

One health and planetary health |

2 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

NL |

|

|

Research and development |

3 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

FR |

|

|

Strengthening the World Health Organization (WHO) |

4 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

SE |

|

|

Digitalisation of health systems |

5 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

EU |

|

|

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) |

6 |

4 |

8 |

5 |

FR |

|

|

Work safety / International Labour Organization (ILO) |

7 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

NL |

|

|

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) |

8 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

NL |

|

|

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) |

9 |

9 |

7 |

8 |

NL |

|

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) |

10 |

7 |

10 |

10 |

FR |

|

As already hinted at in the analysis of word frequency, significant synergies between Germany and France emerge around research and development. Of the 10 topics, this one is addressed most extensively in the French strategy. A more mixed picture emerges concerning strengthening WHO: While Sweden is most involved here, supporting WHO ranks only mid-level among the agenda points in the other documents.

Regarding the digitalisation of health systems, it is again the EU strategy that contains the most references, while this aspect is clearly subordinate for the other partners. The focus on “Universal Health Coverage” is also very mixed. France pays the most attention to this concept, which was also evident in the overview of the strategies. The strategy documents, however, refer to occupational health and the “International Labour Organization” (ILO) almost equally as often, with the Netherlands addressing this issue somewhat more extensively.

The already mentioned relevance of the Netherlands as a partner for Germany is also evident in the topics of “Antimicrobial Resistance” (AMR) and “Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights” (SRHR). Both points rank low on the priority scale of the EU and France and are only mentioned more frequently in Sweden’s strategy. The strongest reference to “Neglected Tropical Diseases” (NTD) is made in the French strategy. In the other three strategies, this aspect ranks last.

Overall, this analysis allows for identifying the potential main partners of German engagement. These are shown in the last column. A particular closeness emerges to the Netherlands strategy, whose priorities align with the German ones in four out of ten points. Next are France with three and the EU with two classifications as top partners. Ultimately, Sweden only gains significance in one aspect, the strengthening of WHO.

Alignment of initiatives

The analysis shows that Germany can find strategic partners in several areas among EU member states and the EU itself. The greatest content proximity is seen with the Netherlands, particularly in the areas of “One Health”, “Planetary Health”, climate, and the environment. These substantive overlaps provide a solid foundation for close collaboration and joint initiatives in global health policy. France is another important partner for Germany, especially in research and development and concerning UHC. The French strategy also emphasises access to medical care, which is another commonality. The EU strategy has intersections with the German one in the areas of cross-border health threats and digitalisation of health systems. Despite differences in other areas, the EU remains an important actor for Germany, mainly due to its role in coordinating and supporting the member states concerning cross-border health threats. Sweden uniquely focuses on WHO and strengthening the international health architecture. Although this creates a greater distance from the German strategy regarding the content, Sweden should be a central partner in German initiatives concerning WHO and global health institutions.

Blind spots in the strategies

Although the strategies of the EU and its member states address numerous aspects of global health policy, there are still blind spots, meaning topics that are hardly addressed or not at all. This becomes particularly evident when compared to the “US Global Health Security Strategy”.

Unlike the US strategy, all of the documents that were examined lack references to the foreign and security policy relevance of global health efforts. Such references could, for example, be made by considering the health policy actions of systemic rivals, such as China, in various world regions or by geopolitically contextualising one’s own efforts. Moreover, the European strategies hardly reference the concept of distributional justice (“Equity”). The US strategy deals with this much more extensively and links equity to inclusion.

Notable in the US strategy is also the explicit prioritisation of bilateral partnerships over multilateral approaches. This contrasts directly with Germany, where multilateral action is the focus. Especially from this perspective, it is advisable to develop joint European approaches, create synergies, and form new partnerships.

Recommendations for further implementation by 2030

The analysis reveals significant differences in strategic priorities and underscores the need for greater integration of approaches. The following measures are recommended for German and European policy to improve the effectiveness and coherence of efforts:

-

Strengthen EU coordination: The EU should provide a stronger platform for the mutual consideration of strategic priorities. In its role as a coordinator, the EU could promote better alignment and greater coherence of national strategies. One possibility would be to go beyond project coordination and, based on the outlined priorities, establish member state working groups that pursue health policy goals through the division of tasks.

-

Consider other strategies in further implementation: The health strategies of the EU and its member states make little reference to each other, which has so far hindered effective integration. During the review process, Germany should consider the national priorities of other countries with the help of EU bodies and, through the EU, seek cooperation with member states.

-

Intensify bilateral and multilateral dialogues: Regular coordination meetings between health ministries and relevant institutions can help identify common priorities and bridge differences. Informal inter-ministerial exchanges on specific areas are also a viable option.

-

Develop joint projects and research initiatives: The development and implementation of joint research projects – particularly in the areas of “One Health”, pandemic preparedness, and digitalisation – could strengthen cooperation and create synergistic effects. Here, too, the EU can play a role as a hub for intergovernmental cooperation.

Overall, the examination of the strategy documents shows that the German government has numerous opportunities for fruitful collaboration with EU member states in global health policy. However, the EU must fulfil its important role as a coordinator. Through close cooperation with the Netherlands, France, Sweden, and the EU, Germany can pursue its goals even more effectively and contribute to strengthening global health. Ultimately, this also requires alignment with political practices and the implementation of the strategies. Uncovering shared interests, which this analysis has done, can serve as an important basis for evaluating the state of cooperation in the individual areas of action.

Michael Bayerlein is an Associate in the EU / Europe Research Division at SWP, where he works on the project “Global and European Health Governance in Crisis” funded by the Germany Federal Ministry of Health (BMG).

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C43

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 44/2024)