Dr Steffen Angenendt is Head of the Global Issues Division.

Nadine Biehler, David Kipp and Amrei Meier are Associates in the Global Issues Division.

This study was prepared within the framework of the research project “Forced Displacement, Migration and Development”, funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

■ The December 2018 Global Compact on Refugees reaffirmed the international community’s commitment to refugee protection – yet willingness to accept refugees is in decline globally.

■ No progress has been seen in the search for viable modes of responsibility-sharing. With the exception of Germany, all the main host countries are middle-income or developing countries.

■ In a situation where more people are forced to leave their homes than are able to return every year, the more affluent countries must shoulder more responsibility. That would mean pledging more resettlement places and increasing public and private funding to relieve the poorer host countries.

■ Aid organisations regularly find themselves faced with funding shortfalls. As the second-largest donor of humanitarian and development funding, Germany should campaign internationally to expand the available financial resources and improve the efficiency of their use.

■ None of the new funding ideas will master the multitude of demands on their own. New and pre-existing financing instruments should therefore be combined.

■ The German government should collect experiences with the different funding approaches in its new Expert Commission on the Root Causes of Forced Displacement (Fachkommission Fluchtursachen). The Global Refugee Forum, which meets for the first time in December 2019, provides an opportunity to start a discussion on new ways of mobilising the required funds for international refugee protection.

Table of contents

2 Background: Why the Need for Action?

2.1 Forced displacement: Global trends

2.2 Fragility and responsibility-sharing

2.3 Global Refugee Compact defines international framework

3 Underlying and Current Funding Problems

3.2.1 Transparency and accountability

3.2.2 Ownership and participation

3.2.3 Efficiency and effectiveness of financing arrangements

3.2.4 Integration of humanitarian aid and development cooperation

4 Additional Financing Instruments and Actors

4.1 Additional public funding and greater flexibility

4.2 Blended finance and guarantee instruments

4.3 Concessional loans and grants

4.6 Mobilising private finance

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1 (1) Secure permanent basis for public funding

5.2 (2) Integrate short-term and longer-term aid

Issues and Recommendations

The willingness to accept refugees has declined globally. Many industrialised countries in particular have tightened their asylum legislation, making the process more restrictive and worsening the living conditions of asylum seekers. Governments have been working to reduce refugee numbers and restrict new arrivals through agreements with transit states and stricter controls at external borders. The advocates of a harder line allege that the right to asylum has been abused for purposes of immigration and assert that refugees create unacceptable economic and social burdens. Critics of the restrictive line accuse their governments of violating the Geneva Refugee Convention, other international norms and national laws, and call for a more humane approach. In the course of these developments, refugee policy (and immigration as a whole) has become a central political conflict in Europe and elsewhere.

One result of the contentious political debate is a lack of coherent and sustainable approaches to international responsibility-sharing and its funding. The actions of the members of the United Nations have been contradictory: In the New York Declaration of December 2016 they agreed to seek closer cooperation and burden-sharing in refugee and migration policy, and concretised this in December 2018 with the Global Compact on Refugees and the Global Compact for Migration. But the Compact on Refugees has not to date led to any fundamental improvements in permanent resettlement in third states or voluntary return, nor has there been any meaningful increase in funding. The few pilot projects have been restricted to just a handful of countries. In view of the large numbers of refugees, it is obvious that financial aid to the (mostly poorer) countries that host most of them needs to be increased. No refugee policy can be effective without adequate funding.

The figures for refugees and internally displaced persons are indeed at historic highs. More people are seeking refuge from violence, persecution and war than at any other time since the end of the Second World War. At the same time the duration of refugee situations is increasing. While the humanitarian funding provided by the international community has increased in recent years, the needs have increased even more strongly in the same period. Aid organisations often find themselves able to acquire only a fraction of the required funds, leaving a growing gap between needs and available means.

So new funding possibilities need to be sought. Three questions must be answered: 1. Why is there a need for international action on refugee protection in the first place? 2. Is there really a funding shortfall or are existing resources being used inefficiently? 3. How can additional funds be mobilised?

These are questions the German government should also be addressing. As the only high-income country among the main destinations for refugees, Germany attracts international attention and enjoys special legitimacy. It is in Germany’s own interests to advance the search for new funding instruments.

The German government should advocate both an increase in the amount of available funding and improvements in its effectiveness. Financing instruments should be transparent and configured in such a way as to strengthen ownership and participation of refugees and internally displaced persons and to facilitate close coordination between the central actors in humanitarian aid and development cooperation. They should also ensure long-term funding. No single funding instrument can address such a diversity of requirements; various approaches therefore need to be combined and applied in parallel.

Direct payments and micro-finance services for refugees and internally displaced persons are especially suited to promoting self-reliance and should be expanded in the interests of efficacy. New financing instruments need to be sustainable and also benefit the host communities.

In order to generate additional funding for refugee assistance, the German government should press for all members of the OECD to meet the agreed target of spending 0.7 percent of GNI on development cooperation. Germany could set a good example by doing so itself. As a major donor it could also ensure that the financial resources it provides for refugees and internally displaced persons are more needs-oriented, untied, long-term and timely. This could be accomplished through pooled funds, which also offer possibilities to optimise the coordination of humanitarian aid and development cooperation.

Other potential sources of new funding include leveraging private finance using public resources, especially in the scope of the European Union’s next Multiannual Financial Framework, reducing the costs of financial transfers, and creating “refugee bonds”. Additionally, the potential of concessional loans and grants has yet to be exhausted.

These financing instruments will only be effective in a framework of closer international cooperation. The German government should therefore improve its coordination of refugee assistance with other donors, and in the process also expand cooperation with “new” donor countries and philanthropic sources (diasporas, businesses, foundations). To support such developments it should push for greater progress in international exchange on funding options in the course of implementation of the Agenda 2030 and the Global Compacts on Refugees and Migration, and feed the results into the corresponding forums, especially the Global Forum on Migration and Development (GFMD). Finally, it should use new and existing national forums – including the new Expert Commission on the Root Causes of Forced Displacement (Fachkommission Fluchtursachen) – to hone Germany’s approaches to funding refugee assistance.

Background: Why the Need for Action?

Numbers of refugees and migrants are growing globally, while the distinction between the two groups becomes increasingly blurred.1 This development makes it increasingly difficult for states to fulfil their duty to protect refugees, and many fail to do so. National isolationism is a growing trend, eroding global refugee protection and leaving weak and fragile states bearing the brunt of the burden. The costs of refugee protection are increasing while – in the context of the international community’s fundamental commitment to responsibility-sharing in the Global Compact for Refugees – pressure is growing to find suitable international approaches for funding refugee protection.

Forced displacement: Global trends

Global trends in internal and international forced displacement give grounds for concern: the number of refugee situations is increasing, as is their duration. At the end of 2018, the UNHCR estimated, “almost 70.8 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations”. Of these, 25.9 million were international refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, 5.5 million Palestine refugees under UNRWA’s mandate and 41.3 million internally displaced persons. There were also 3.5 million asylum-seekers.2

Those figures represent a new record since the Second World War. The most recent increase is associated in particular with the Syrian refugee situation, where numbers remain high and rising, but also with refugee movements in Sub-Saharan Africa.3

Most people who flee their country of origin remain in the region and seek refuge in neighbouring states. These are often the poorest countries: At the end of 2018 84 percent of refugees under UNHCR’s mandate were living in developing countries, one-third of them in the least developed countries.4 In all of the ten main countries of origin of refugees (Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Eritrea, Burundi) the situation causing displacement had already existed for more than five years in 2018.5 Internal displacement situations are also increasingly protracted.

At the same time the prospects of finding lasting solutions are receding. UNHCR regards voluntary repatriation, resettlement and local integration as “durable solutions”. According to the statistics, 13.6 million people were newly displaced in 2018 but only about 2.9 million were able to return to their areas or countries of origin. Although UNHCR did record an 8 percent year-on-year increase in resettlement places provided by states in 2018, the number remained so small that it was only possible to realise about one-tenth of the resettlements requested by UNHCR.6 In the case of the third lasting solution, local integration, recent developments have largely been negative7 (alongside minor improvements such as new legislation in Ethiopia permitting refugees to live and work outside of refugee camps and easing their access to official documents such as birth and death certificates8).

Fragility and responsibility-sharing

Fragile and weak states are especially affected by the changes in global forced displacement.9 These countries host a large proportion of the forcibly displaced and face growing difficulties coping with the ensuing challenges. They generally lack the necessary structures and financial resources, and the task of supporting and protecting the forcibly displaced frequently exceeds their economic, political and social abilities. Under conditions of fragility the presence of large numbers of refugees and internally displaced persons can exacerbate pre-existing competition for natural resources like water, land and firewood, deepen poverty, and accelerate exclusion and radicalisation, potentially leading to increases in crime, violence and political instability. Exploitation and discrimination are common side-effects of refugee situations, and human rights often fall by the wayside. Under adverse circumstances forced displacement can also hinder a broader reduction in poverty, interfere with economic growth, threaten the environment and thus also undermine realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agreed in the Agenda 2030. These problems affect both forcibly displaced and host populations.10

Forced displacement under conditions of state fragility can thus represent a considerable impediment to development, and in the worst case eliminate progress already made. The risk of such trajectories occurring is almost certain to rise in connection with the growing numbers of people living in fragile situations. The World Bank estimates that the number of people living below the poverty line in fragile contexts will increase from 513 million in 2015 to 620 million in 2030, with more than 80 percent of the world’s poor experiencing situations characterised by precarity, conflict and violence.11

The states that host refugees and internally displaced persons – granting them protection and providing for them – are addressing immediate need, fulfilling a humanitarian mission. This support for refugees and internally displaced persons represents a contribution to international burden- and responsibility-sharing and is understood by certain international actors as a global public good.12 Yet the governments in question frequently have no choice but to take these people in if they wish to avoid a humanitarian crisis on their borders.

Global decline in willingness to share responsibility for refugees.

In fact, countervailing trends are observed in protection and funding: On the one hand there is a broad consensus within the international community that refugee protection is a collective task. On the other, the willingness of states to share the burden and take in refugees has been seen to decline globally. Examples include cuts to the US Resettlement Programme, as the world’s largest, but also the longstanding inability of EU member states to agree practical responsibility-sharing measures.13 Given that context, it is all the more important that public and private funds for refugee protection are sufficient, predictable, timely and long-term.

Global Refugee Compact defines international framework

In response to large and growing movements of refugees and migrants, the UN Secretary-General held a summit on the issue in September 2016. At that gathering the member states adopted the New York Declaration and agreed to prepare a Migration Compact (Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration) and a Refugee Compact (Global Compact on Refugees). Both documents were signed in December 2018. While the Global Migration Compact provoked sometimes heated debates within member states and was rejected by a number of governments, the more practically orientated Global Refugee Compact was less controversial and gathered more signatories.14

The Refugee Compact comprises two elements: a Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF) already adopted with the New York Declaration, which codifies principles for cooperation in refugee crises, and a Programme of Action listing concrete measures and procedures to be observed in refugee protection. The Programme of Action also contains proposals for supporting states hosting refugees, meeting the needs of refugees and host communities, and finding lasting solutions. Altogether the Refugee Compact is intended to supplement rather than replace the Geneva Refugee Convention of 1951, which remains the backbone of international refugee protection.

The commitments laid out in the Refugee Compact include greater support for host countries, above all by explicitly strengthening the capacities of the affected communities, as well as improving economic perspectives for refugees (through measures including work permits and training) and replacing refugee camps with individual accommodation. Overall, the Compact seeks to improve coordination of activities between providers of humanitarian aid and of development cooperation.

Refugee Compact offers new opportunities for international cooperation.

Altogether the Refugee Compact offers a collection of useful proposals and already known “good practices” from the spheres of humanitarian aid and development cooperation. But it is ultimately a non-binding declaration of intent. It names no quantitative targets (for which indicators have yet to be developed). The multitude of measures mentioned in the Compact makes it easy for donor countries to cherry-pick the approaches they find most attractive. The same applies to funding for refugee assistance: While the Refugee Compact calls for additional financial resources to be mobilised, it remains unclear where the required funding is supposed to come from – leaving aside general suggestions such as the call to increase private sector involvement. So the Compact is unconvincing in relation to future funding for refugee protection.

This assessment is confirmed by the initial experience in CRRF pilot countries, where there has already been controversy over inadequately clarified funding issues. For example Tanzania and Uganda received much praise in recent years for taking in large numbers of refugees and operating a generous refugee policy. But in February 2018 Tanzania withdrew from the CRRF citing differences with donor countries over funding for aid measures and refusal to take out (concessional) World Bank loans to fund refugee accommodation. Instead they expected grants. When the donors declined, Tanzania terminated its CRRF cooperation.

In the case of Uganda too, disagreements over financing hindered the implementation of refugee assistance. Donor countries are presently reviewing the cooperation after allegations emerged that Kampala had inflated refugee counts and misappropriated aid funds. Despite these difficulties, experience in pilot countries shows that the CRRF is a step in the right direction – not least because it can offer ad hoc financial support to countries that may have been hosting refugees for decades.15

Other important host countries have also raised demands of their own. Pakistan points to its 1.4 million registered refugees to press for greater financial support – and adds that this should be supplied as grants rather than loans in order to avoid creating additional financial burdens. Iran goes a step further to demand a lump sum per refugee and year.16

These implementation examples demonstrate the importance of the Global Refugee Compact in the search for new and effective approaches in refugee policy. They also underline the centrality of the funding question for future refugee protection.

Underlying and Current Funding Problems

The political debate about financial support for refugees and internally displaced persons revolves essentially around the question of whether there is a genuine lack of funds and a real scarcity of resources available for protection, provision and local integration,17 or whether the available funds are incorrectly allocated and the actual problem is inefficiency of humanitarian and development spending in situations of forced displacement.18

This controversy resurfaces in all the relevant international processes: The Global Refugee Compact also stresses the demand for stronger financial engagement by donor states, arguing that international burden- and responsibility-sharing must first and foremost tackle inadequate funding because the developing countries are most strongly affected by forced displacement.19 On the other hand, the World Humanitarian Summit called by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in May 2016 in Istanbul – as the first global forum for consultations between governments, humanitarian organisations and civil society on growing global humanitarian needs – concentrated on efficiency issues.20

Insufficient funds

It is not possible to precisely quantify the volume of international financial resources available for refugee situations. Information is frequently missing and the existing data is often not comparable. Calculations of humanitarian needs are often not very transparent, opening aid organisations to accusations that their appeals are exaggerated (“appeal inflation”).21 Finally, the two different policy areas involved in refugee assistance – humanitarian aid and development cooperation – differ strongly in terms of their objectives, approaches and financing instruments.

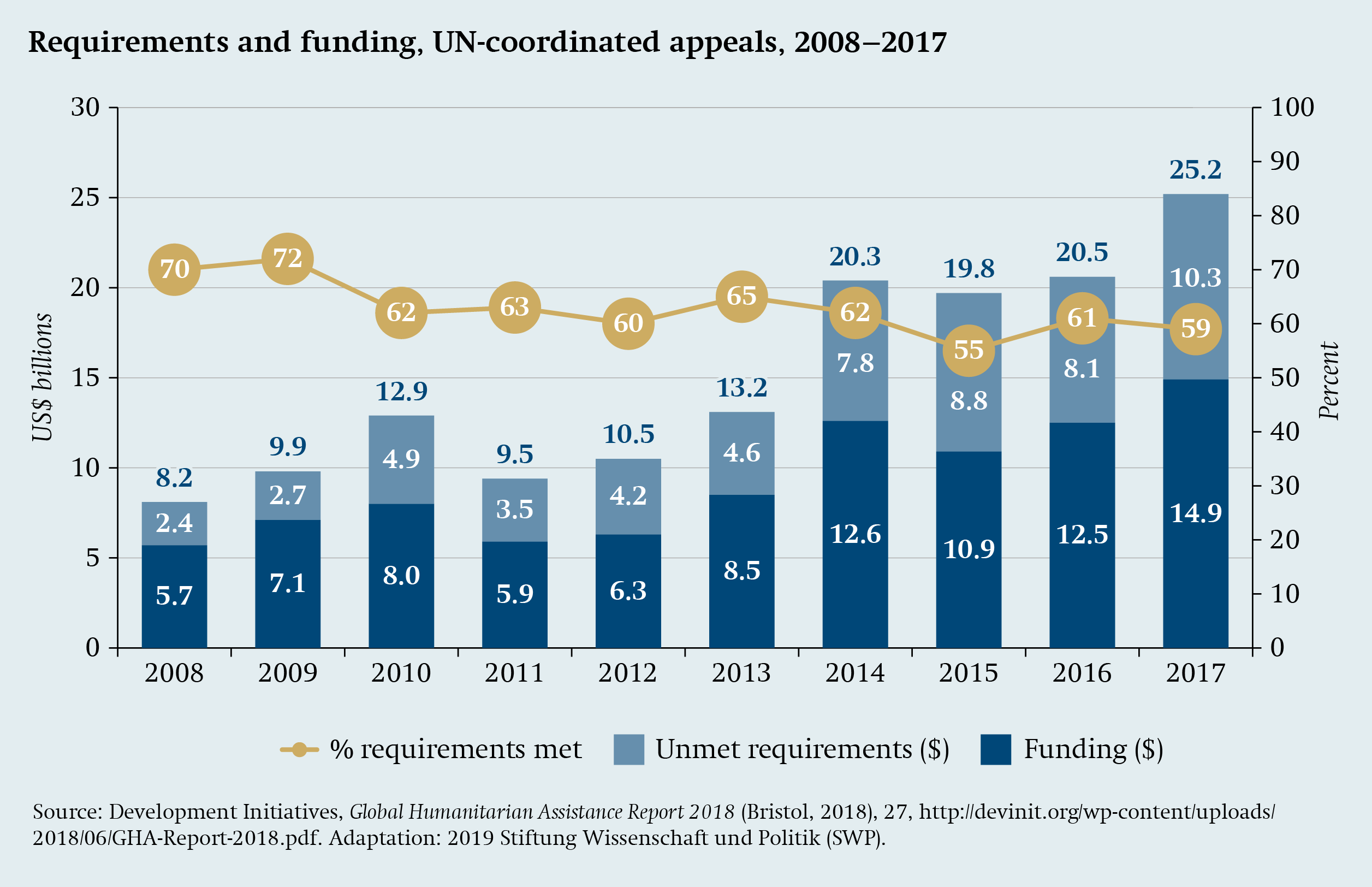

In humanitarian aid the resources required by UN aid organisations are budgeted annually and aggregated. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) then registers the contributions committed by donor countries. While this method is not without its flaws, it does expose the clear gap between needs stated and resources provided. In past years the needs were never met in full (see Figure 1, p. 12). Even in 2017, when humanitarian aid reached a new record of $27.3 billion, it was far from satisfying the needs.22

The UNHCR, as the central UN actor supporting refugees and internally displaced persons, is especially affected by funding shortfalls. In 2018 its funding requirement was $8.2 billion, of which donor countries provided just $4.7 billion (corresponding to a shortfall of about 43 percent).23 As such the funding gap remained roughly constant in comparison to 2017.24 The shortfall could in fact grow if the United States carries through its threat to further cut its contributions to the UN and thus also the UNHCR.

Development cooperation, in contrast, is about sustainable change rather than immediate survival. While the short-term costs involved in humanitarian aid – for accommodation or food and water – can be quantified relatively precisely, it is harder to compare annual needs and resources in development assistance, which is structurally long-term. Development funds committed by OECD member states are recorded by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and coded by sector (for example health or education). This makes it possible to track the purposes for which member states provide funds. But the Committee did not begin discussing breaking down spending on refugees and migrants until 2015, in response to the large-scale refugee movements to Europe. In this context the member states agreed that donor countries could include the costs of the first twelve months of accommodation and support for refugees and asylum seekers in their official development assistance (ODA).25

Funds channelled largely into short‑term projects.

Until the results of this new calculation are published, we have only estimates to go by. The OECD Development Assistance Committee estimates that between 2015 and 2017 about $26 billion was spent on supporting refugees and their host communities, most of which was categorised as humanitarian aid. While the Committee acknowledged that donor countries had tried to improve coordination between development-led approaches and short-term emergency aid,26 it also noted that the proportionally higher rise in spending on humanitarian aid demonstrated that crisis response was still being prioritised over sustainable and preventative measures. Additionally, the Committee noted, donor countries were still reallocating funds intended for long-term need-reduction measures to short-term objectives.27

Despite the inadequacies of the data, it is clear that the funds provided for humanitarian aid and development cooperation do not at present cover existing needs. In addition, it is the poorest developing countries that are most affected by the consequences of forced displacement. Their economic weakness means that they face special pressures if they are forced to divert their own resources into humanitarian crises because international aid is insufficient. Thus in 2016 official development assistance and humanitarian aid represented respectively just 6.9 percent and 1.7 percent of the total international financial flows to the twenty largest recipients of humanitarian aid.28 Like any other, these governments have to justify spending scarce budget funds on refugees to their own citizens. In general the official figures for spending on refugees given by host countries tend to be unreliable,29 as are the figures for refugee populations: Higher figures can be helpful for negotiations with donor countries.30

|

The German contribution to international refugee protection Germany has significantly stepped up its efforts in recent years. In 2018 it became the second-largest donor of humanitarian aid and development assistance after the United States, with a total of €21 billion (or 0.61 percent of GNI).a According to its own figures the German government spent about €6.5 billion on tackling the root causes of forced displacement in 2016, and more than €7.3 billion in 2017.b The 2019 budget for this category of development cooperation and humanitarian aid is (as in 2018) €6.9 billion. These funds are employed above all to address structural causes (preventing violent conflicts, compensating for failure of state institutions, reducing poverty, inequality, lack of prospects and the consequences of climate change) as well as measures designed to improve opportunities for refugees and displaced persons in host regions.c |

|

a Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ), “Deutsche ODA-Quote 2018 verharrt bei 0,51 Prozent ohne Inlands-Flüchtlingskosten: Vorläufige ODA-Zahlen”, press release, Berlin, 10 April 2019, http://www.bmz.de/20190410-1 (accessed 28 June 2019); Ralf Südhoff and Sonja Hövelmann, Wo steht die Deutsche Humanitäre Hilfe? (Berlin: Centre for Humanitarian Action [CDA], 20 March 2019), 2. b Deutscher Bundestag, 19. Wahlperiode, Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der FDP-Fraktion: Engagement der Bundesregierung für die Bekämpfung von Fluchtursachen, 12 October 2018, Drucksache 19/4955, 5. c Idem, Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der FDP-Fraktion: Effiziente und nachhaltige Bekämpfung von Fluchtursachen, 31 July 2018, Drucksache 19/3648, 2f. |

In short, the analysis shows that developing countries especially affected by forced displacement fail to receive adequate international support. Despite spending their own funds they are often unable to sufficiently support forcibly displaced persons and their host communities. These problems can be expected to grow.

Inefficiency

The second important aspect of refugee financing is (in)efficiency of spending. There have long been complaints about the inadequate effectiveness of support and discussion of possibilities for improving it. Corresponding recommendations and criteria for development cooperation and humanitarian aid have emerged from numerous international forums and processes,31 some of which are especially relevant for financing refugee assistance.

Transparency and accountability

Transparency and accountability are preconditions for efficient aid allocation and spending. Their observance can contribute to reducing transaction costs, waste, corruption and mismanagement.32 This applies especially to international refugee assistance, which requires accurate data on numbers. In reality, however, refugee statistics are frequently incomplete.33 The case of Uganda raised eyebrows in 2018, when it was revealed that the government had inflated the number of refugees by 300,000 and that the UNHCR country office had been too slow in following up on reports indicating the issue.34 This example underlines the importance of reliable data on numbers of refugees and their humanitarian and socio-economic situation for the accountability and ultimately also the legitimacy of international refugee protection.

Ownership and participation

In order to improve efficiency in the use of funds, there are increasing calls for greater ownership by recipient governments and refugees themselves. This is also associated with discussion about making better use of the institutions and administrative structures of the recipient countries and involving national and local (humanitarian) actors more closely in refugee assistance (“localisation”). More resources should flow to local and national organisations: at least 25 percent of global humanitarian aid by 2020.35 Not least, refugees and internally displaced persons should be more closely involved in developing and implementing the instruments: The “Grand Bargain” agreed in 2016 in Istanbul even calls for a “participation revolution”.36 Promoting ownership and self-reliance of refugees and internally displaced persons makes sense from the perspective of donor countries, because long-term accommodation in large camps is costly. In the medium and long term it is cheaper and more sustainable to integrate refugees and internally displaced persons into national systems instead of setting up parallel structures – especially as the local population also benefits. This approach is also associated with a hope that strengthening institutions in host countries might obviate potential distribution conflicts between refugees and the local population.

Involving refugees more closely should make assistance as a whole more targeted, cost efficient and sustainable.37 In comparison to other humanitarian emergencies, refugee situations present special challenges for participation. Apart from that, refugees are as a rule excluded from formal channels of participation (for example the right to vote and stand in local elections).38 In fact many governments also struggle with participation by internally displaced persons, especially where they speak a different language than the local population and/or differ in religious or ethnic terms. It is therefore all the more important for the success of aid programmes to involve refugees and internally displaced persons in designing measures from the outset.

Efficiency and effectiveness of financing arrangements

Great hopes are placed in particular on cash assistance, which offers recipients greater choice and can strengthen local markets.39 It can also be more cost-effective than traditional food assistance and enables more people to be supplied.40

International organisations engaged in humanitarian aid also regularly argue for more flexible multi-year financing. They believe that this would reduce administrative costs for donor countries and aid organisations, and achieve better results through longer planning horizons.41 Unearmarked financing could also ensure that investments are made even in fragile situations and facilitate timely response to urgent and rapidly-emerging needs.42

These proposals are especially relevant for the context of forced displacement. However, in 2018 just 11 percent of UNHCR funding was unearmarked,43 and only 2 percent was committed as multi-year financing.44 Here it would be up to donors to make good on their promises.

Integration of humanitarian aid and development cooperation

Humanitarian aid and development cooperation are characterised by different objectives, principles and approaches, some of which stand in direct contradiction to one another. For example, humanitarian principles require neutrality and independence, whereas development cooperation works with – and seeks to strengthen – local actors and structures.45 Altogether there is a broad consensus that the interplay needs to be improved in order to respond to crises more effectively and sustainably.46

This gap is especially obvious in the context of forced displacement.47 The integration of the two spheres is indispensable for refugee protection: on the one hand, forcibly displaced persons require emergency aid to ensure their survival. On the other hand the increasing duration of refugee situations also necessitates the longer-term approaches of development cooperation. The latter include for example vocational training to offer refugees and internally displaced persons a future and promote self-reliance.

Additional Financing Instruments and Actors

In response to the funding problems and conceptual and political weaknesses of refugee assistance, there is discussion about what instruments can be used to meet the need for additional resources in this sphere and how the efficiency of assistance can be improved. The proposals span a broad spectrum, from tapping additional public funds to finding new donors.

Additional public funding and greater flexibility

One very obvious proposal is to provide additional public funding. As far back as 1970 the UN General Assembly recommended that the economically developed countries should provide public development funding representing 0.7 percent of their GNI starting in 1975 (ODA/GNI ratio). Few countries ever achieved this, the exceptions being Sweden, the Netherlands, Norway and Denmark. Finland, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom have met the target once or more.48 Germany also reached this threshold in 2016, above all on account of that year’s especially high spending on refugees within the country – the so-called “in donor refugee costs”.49 Overall, however, even in 2016 average spending by members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee was substantially less than 0.4 percent of their GNI.50 In view of its lack of success, the point of the ODA ratio as a political target is regularly called into question.51 On the other hand, the consistent international support for the 0.7 percent target suggests that many states continue to believe it should remain a guideline.52 German Development Minister Gerd Müller has – like his pre-predecessor Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul – argued for the target to be retained.53

Even where a growing need for refugee assistance demands rapid action, it would not be advisable to reallocate development funds at short notice to be spent on supporting refugees, internally displaced persons and host societies. The needs in other spheres of development finance are not declining and reallocation would tear new holes and endanger ongoing development projects. On the other hand, increasing funding as a whole would be a useful step towards achieving the 0.7 percent target.

One important aspect of the debate over public development funding concerns so-called untying of aid. For a long time it was customary for donors to make development funding conditional on goods and services being purchased exclusively in the donor country. While obviously advantageous for donor nations, this increased the costs of development projects – experience suggests by up to 30 percent. In the meantime, guidance from the OECD Development Assistance Committee has contributed to almost doubling the untied share of aid from 41 percent in 1999–2001 to 79 percent in 2018.54 Ending aid tying altogether could allow recipient countries to profit even more from development funding, which would also be helpful for addressing refugee situations.

Blended finance and guarantee instruments

One option for expanding financial resources would be to blend public development funding more strongly with private resources “blended finance”). Development banks and international financial institutions already have years of experience in “leveraging” public funds. Between 2000 and 2016 a total of 167 such facilities were launched.55 But their formats and objectives varied widely. At the end of 2017 the OECD states agreed for the first time on a shared definition for this instrument, under which “blending” is “the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries”.56

Whether and to what extent blended finance instruments can really contribute to sustainable development and poverty reduction remains a matter of debate. One problem is the level of expected returns on investments in public goods, which is frequently decisive for private investors – who tend to prefer to invest in middle-income countries (with lower risks).57 With respect to the need to support refugees and internally displaced persons, countries like Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon would therefore appear more suitable for blended finance instruments than economically less developed countries and fragile states with protracted refugee situations.

Growing significance of blended finance instruments.

The importance of blended finance for development cooperation continues to grow despite these concerns. Since 2007 the EU has established eight blending programmes for the target regions of EU development policy, with a total budget of €3.4 billion. The provision of those funds has led to lending totalling €26.2 billion and estimated investment of €57.3 billion in the partner countries. In addition, in the EU budgetary period 2014 to 2020 the European Investment Bank (EIB) was authorised to guarantee loans outside the EU totalling €27 billion. In 2018 the EU increased the volume to €32.3 billion and expanded the programme to include “root causes of migration”.

Establishment of the External Investment Plan (EIP) in 2017 involved the creation of a new fund, the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD), designed to encourage private investment in developing countries. Unlike previous financing instruments, the EIP is managed by the European Commission rather than the EIB. It is also entitled to grant guarantees to other investment banks and private investors within and outside the EU. Under the EIP framework partner countries are offered support for improving their investment conditions.58 A total of €4.1 billion from the EU budget and the European Development Fund is supposed to feed into the EFSD by 2020, creating a base capable of leveraging €44 billion in investments. The EIP’s investment policy is strategically orientated on the EU’s foreign policy objectives, as such also channelling private-sector capital to African countries that show willingness to cooperate on migration issues and contributing to improving the employment prospects and livelihoods of people there.59 A major donation of €50 million came from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.60 Despite this growth it is too soon to tell whether the instrument can meet expectations and whether the expected leveraging effect is realistic.61

Even if the member states have not to date provided additional funds for the EIP, the EU Commission plans to expand this investment offensive in the EU’s next Multiannual Financial Framework. It is proposing that a considerable proportion of the new Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument should flow into an expanded “EFSD+” comprising up to €60 billion.62 This measure could contribute to improving coordination of the investment decisions of the EIB, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the national development banks (above all the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau and the French Agence Française de Développement).

Closer exchange with development banks in the partner regions is certainly needed. A new platform for exchange between multilateral development banks was established in spring. These financial institutions want to inform themselves more fully about approaches in the field of forced displacement and migration and coordinate their projects better with one another.63 The African Development Bank in particular has recently begun devoting greater attention to the topics of forced displacement and migration.64

Concessional loans and grants

Many of the world’s refugees are hosted by middle-income countries. Although these states are often operating at the limits of their financial abilities and at risk of overindebtedness, they are generally denied access to concessional loans at advantageous terms from development banks. Such loans – which come with conditions as favourable as 1 percent interest and repayment periods exceeding thirty years – have to date been granted only to low-income countries.

For example Jordan and Lebanon, as two of the main countries hosting Syrian refugees, face great financial challenges. In order to support these two middle-income countries the World Bank established the Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF) in April 2016 as a joint project with the United Nations, the Islamic Development Bank and other actors. The GCFF supports middle-income countries that have taken in large numbers of refugees through concessional financing of development projects.

The GCFF is designed to reduce interest rates to concessional levels with the help of donor contributions. The donor countries’ funds are supposed to be used to tie loans from so-called implementation support agencies to conditions. These agencies are development banks that offer low-interest loans and possess development expertise. The hope here is that the leveraging effect will release about four dollars in concessional loans for every dollar provided by donors.65

The mechanism is currently funding seven projects in Jordan and four in Lebanon.66 The priority areas are infrastructure (especially water supply and treatment and energy), job creation and improving economic perspectives for locals and refugees. Colombia was granted $31.5 million from the GCFF in April 2019.67

To date nine countries and the European Commission have supported the GCFF financially. As of June 2018, $574 million had been promised or already paid out, releasing concessional loans totalling $2.5 billion. The biggest donors were Japan ($110 million), the United Kingdom ($87 million) and the United States ($75 million). Germany also supports the fund financially: as of June 2018 the German contribution was €20 million, provided for Lebanon and Jordan.68

However, some observers criticise the GCFF’s cumbersome and state-centred funding policies. NGOs and SMEs have to date been excluded from access to the funds.69 Expanding access to NGOs and SMEs would enhance their flexibility and offer them more cost-effective solutions without transaction costs. Even more importantly, such a step would conform with the “Grand Bargain” promise of localisation.70

Concessional loans can target support especially effectively.

Since mid-2017 the World Bank has also been providing additional funding to support refugees in low-income countries. The International Development Association (IDA), the World Bank’s division for the world’s poorest countries, was provided with a sub-window of $2 billion for the period until mid-2020 specifically for refugees.71 The initial eight recipient countries (Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Niger, Pakistan, Uganda) were joined by five more in 2018 (Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Mauritania, Rwanda).

The IDA is used to promote refugees’ access to education and integration in the labour market, and to support host communities. It is also supposed to strengthen state institutions and economic and rule-of-law structures. The recipient countries (with one exception) currently receive financial support as half grant, half concessional loan.72 However the obligation to repay (at least a part) could discourage take-up. Reservations of that kind have already led Tanzania to withdraw from the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF), which was established as part of the Global Refugee Compact.73

Funding through the Global Concessional Financing Facility and the IDA refugee sub-window is tied to particular preconditions: recipient countries must have taken in at least 25,000 refugees, who must represent at least 0.1 percent of their population.74 The observance of specific standards of protection is required, as is the willingness to develop long-term/ permanent solutions for refugees. Currently the World Bank and UNHCR decide whether a country receives funds. Other aspects also play a role, including the country’s financial situation, its debt burden and the socio-economic impact of hosting refugees.

Like the Global Concessional Financing Facility, the IDA refugee sub-window also represents an important innovation seeking to employ resources in a better and more targeted fashion and to relieve the pressure on host countries. But it would appear questionable whether the 50/50 rule prescribed for the refugee sub-window makes sense. The World Bank’s October 2018 Mid-Term Review therefore proposes further exceptions for acute refugee crises: in future the IDA should be able to “provide 100 percent grants to countries that experience a massive inflow of refugees, defined as receiving at least 250,000 new refugees or at least 1 percent of its population within the last twelve months”.75

Pooled funds

Pooled funds represent another important method for funding humanitarian aid. In this arrangement multiple donors pay their contributions into a fund administered by an international organisation. The UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund has accumulated more than $5.3 billion since it was created in 2006, and provided support in 101 countries.76 Unlike other sources of financing, it enables humanitarian actors to employ resources precisely, quickly and flexibly. Such funds are especially suitable for risky projects: 37 out of 66 pooled funds projects to date were in fragile contexts.77 Additionally this financing method tends to contribute to strengthening local and national humanitarian aid partners. The country-based pooled funds administered by OCHA, for example, are directly accessible to local actors.78

EU Emergency Trust Fund can improve political coherence.

At the end of 2015 the EU merged its financial resources for displacement- and migration-related support for African partner states with the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). This brought together previously separate EU funds for the policy areas external affairs, internal affairs, development cooperation, humanitarian aid and neighbourhood policy in a single fund. Although the EUTF was originally supposed to be a temporary instrument for emergencies, the EU Commission has come to see it as a financing model for the EU’s future external migration policy.

The EUTF has improved both coordination among the EU institutions themselves and their own coordination with the member states. However the member states may in future push more strongly to channel it into containing irregular migration. These funds would then be lacking for long-term support for countries of origin and refugee hosting countries, and for creating legal migration options.79

Emerging donors

While there is not yet a universally accepted definition of the “new donors”, the term is widely accepted to include Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, along with Turkey, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates as well as other Arab states such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.80 Few of these countries are members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee,81 and many of them have only emerged as substantial donors over the past decade or two. Some of them were until recently recipient countries themselves (or even remain so).82 Their designation as “new” donors can be misleading: In particular Arab states like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates have decades of experience as comparably generous supporters, above all of other Arab states.83 But it is also alleged that their aid payments lack predictability and that they pursue geopolitical and economic interests.84

It is estimated that the new donors provided between $10 and $15 billion for development cooperation in 2012, representing about 7–10 percent of total global official development assistance.85 In fact, China became the world’s sixth-largest bilateral donor in 2013.86 But the assistance China provides as loans is a great deal larger, and today Beijing is Africa’s largest creditor.87 Even if reliable data on the financing behaviour of the new donors is often unavailable and their activities rarely comparable with those of other donor countries – for example because their understanding of development cooperation deviates from the DAC standards88 – these countries can be expected to increase their contributions to development finance.89

In relation to refugee situations, however, the new donors’ contributions have been small to date. While China’s share of global GDP in 2017 was about 15 percent (United States: 24 percent), its share of UNHCR funding was just 0.3 percent (against 37.2 percent for the United States). India, which according to the International Monetary Fund has the sixth-largest economy, is not even listed as a state contributor in the UNHCR statistics. Brazil, which in 2017 accounted for 2.7 percent of global GDP, supplied just 0.02 percent of the UNHCR’s contributions.90

“New donors”: great potential, but risks too.

What all the new donors are regarded as sharing in common is that they tie their development cooperation and humanitarian aid to economic and geopolitical interests,91 which is presumably why most of them concentrate their activities in their own neighbourhood.92 Also it is feared that autocratic and corrupt donor countries could represent an obstacle to sustainable development.93 On the other hand, the developing countries do not necessarily regard the resulting diversity of donors as negative, because they can exploit the resulting competition (for example over the degree of conditionality) to their own ends.94 One advantage the new donors possess is that their relations with the recipient countries are not burdened by any colonial legacy – unlike the members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee.

In that context, triangular cooperation between OECD states, new donors and developing countries represents a promising approach. In the scope of such cooperation the financial potential of the OECD states could be combined with the specific knowledge and technical expertise of the new donors, for example in overcoming poverty (such as Brazil’s experience with cash transfers tied to conditions such as children attending school or medical check-ups), and better adapted to the challenges in the target countries. But the potential of such cooperation has yet to be properly researched.95

Despite these uncertainties, the new donors can be expected to play an important role in future financing of refugee assistance: Here their economic and geopolitical self-interest could offer a guarantee that their engagement will be sustainable, for example in dealing with crises and forced displacement in their immediate neighbourhood. International framework agreements such as the Global Refugee Compact, the Sustainable Development Goals and the principles of the Aid Effectiveness Agenda could serve as the shared basis for constructive cooperation between the OECD states, the new donors and the recipient countries.

Mobilising private finance

International refugee assistance is still largely publicly financed, although today one quarter of humanitarian aid already originates from private sources. The recipients of the latter are primarily NGOs.96 The share of private contributions to the UNHCR budget is small on the other hand, although a noticeable rise has been recorded here too: from 2 percent in 2007 to 10 percent in 2017 (from $34 million to $400 million).97 UNHCR is seeking to considerably increase the proportion, hoping to acquire $1 billion annually from the private sector by 2025. Two-thirds of that is to come from individual donors, the rest from businesses, foundations and philanthropists.98

The potential of private support for humanitarian aid extends beyond direct financing. One instrument is “impact investing”, where the investors carry a risk because repayment of the invested capital is conditional on the success of the measure. This concept has been discussed above all in the context of financing the Sustainable Development Goals, but there are also proposals to apply the impact investing model in humanitarian aid too.99 The idea of introducing insurance solutions to cover the financial risk of refugee situations appears less viable,100 above all because the drivers of displacement – such as armed conflict, persecution and massive human rights violations – are uninsurable risks.101

Private funding offers scope.

Another approach proposes using state guarantees to secure loans on the international capital markets, which can then be employed for example to fund vaccination programmes in developing countries. Repayments are made out of future development aid from donor countries. A similar form of public-private partnership is also conceivable for refugee support. “Refugee bonds” could be issued, investing development and humanitarian aid funds in the capital markets in order to create planning security for host countries and incentives for local integration of refugees.102 A proposal to test this approach in a pilot project to improve the living conditions of refugees in Lebanon and Jordan is currently under discussion. The bond initially seeks to raise €25 million in donor contributions and €20 million in investment.103 Under that condition the Ikea Foundation has announced it would take a stake of €6.8 million. The design as an “impact bond” means that the investors initially bear the risk but receive their contribution back from public development funds if a previously stipulated target – such as getting an additional five thousand refugee children into school – is achieved.104 Setting up such a bond is, however, costly and time-consuming.105

In terms of strengthening the local economy, other tried and tested instruments of development cooperation are also available. These include the so-called graduation approach that combines measures for social security, for improving the health services, for financial inclusion, for labour market integration and for vocational training.106 For example the concept of using micro-credit to create safety nets and employment for the poorest developed by the micro-finance institution Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee has been adapted by the UNHCR in a number of countries and employed in refugee situations. In order to strengthen social cohesion, up to one quarter of the project participants should be from the respective host communities. These pilot programmes are also costly and time-consuming. But initial reports suggest that they have positive effects on the income and employment situation of participants.107 Reliable evidence concerning long-term effects is not yet available.108

The inability to acquire a work permit frequently represents an impediment to local integration. This aspect is addressed by the proposal to establish special economic zones, where refugees may be legally employed. In return the firms in question receive favourable trade arrangements.109 This approach has been tested in Jordan, Lebanon and Ethiopia, with limited success to date. The problems became most clear in connection with the so-called Jordan Compact:110 Here it proved almost impossible to find refugees who satisfied the requirements of the textile manufacturers.111

If this approach was tailored more closely to the respective context, it might yet be able to make a contribution to improving the situation of refugees and social cohesion in the host countries and ultimately also reducing the funding needs associated with protracted refugee situations. This has led to discussion about sustainable development zones as a specific iteration of the special economic zone. These would possess their own institutional and legal framework to promote economic activity by refugees.112 But the implementation of such proposals would involve risks in terms of human rights and international law. The associated tax breaks would also be problematic: they could erode important sources of revenue for developing countries,113 while also potentially exposing the affected states to accusations of being tax havens.114

Philanthropy

The engagement of private charitable foundations in development cooperation has been growing steadily for two decades.115 According to an OECD survey the total volume remains small and concentrated in just a few sectors: between 2013 and 2015 private foundations contributed $23.9 billion, representing 5 percent of total official development assistance ($462 billion). According to the OECD, the activities of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation play a significant role in the growth of contributions from major foundations. Because the foundations channel almost all their contributions through implementing organisations (rather than spending it directly themselves) they represent an important source of funding for civil society organisations and NGOs in times when public funding is scarce. To date, most foundation funds have flowed to middle-income countries like China, Ethiopia, India, Mexico, Nigeria and South Africa, rather than to least developed countries. One of the OECD’s criticisms is that such foundations operate largely outside public control and without accountability or transparency.116

Private foundations and diasporas: effective but lacking accountability.

Nevertheless foundations can supply valuable assistance in refugee situations because they can take a longer view. Precisely because they are less publicly accountable, they may be more able to take financial risks and test new ideas and approaches. Also they are often closely connected to the private sector, especially when their capital originates from entrepreneurial activity.

Diaspora philanthropy is also of great relevance for the context of forced displacement. Although critics point to the danger that the interests of members of the diaspora are not necessarily identical to those of the population in the country of origin, or may even contradict development strategies,117 diaspora communities nevertheless frequently supply emergency aid in crises and disasters, engage for the long term or conduct lobbying in the donor countries. It is also observed that increasing migration by the highly qualified leads to growth in the number of wealthy diaspora members, who even in the second and subsequent generations find it easier to maintain contact with the community of origin.

The spectrum of diaspora engagement is very broad, ranging from individual financial transfers through donations to organisations and the establishment of foundations by prominent cultural figures, sports stars and businesspeople. At the same time, especially among diasporas from countries with poor governance, there is often mistrust of their institutions. For that reason donations are frequently channelled directly to the recipient, because that allows the donor to keep better track of where the money has gone. One approach to strengthen the engagement of diaspora actors – also in refugee assistance – might be to promote their capacities (for example in relation to financial management) in the scope of development cooperation.118

Remittances

Research by the World Bank has shown that remittances from migrants have long exceeded the entirety of official development assistance by a factor of three or four, and continue to increase. Thus in 2018 remittances to low- and middle-income countries grew by 11 percent compared to the previous year (to $528 billion). As such they also far exceeded the rise in foreign direct investment in these countries.119

Research into remittances by refugees remains patchy.120 For example it is not possible to distinguish between remittances from refugees and from migrants (who migrated earlier to the country in question). At the same time there is a consensus among researchers that it makes a difference whether people migrate voluntarily or under duress. Financial transfers from refugees are as a rule smaller than those from migrants, because the former generally need time to find paid employment,121 and in general the incentive to send money home is smaller because of the smaller likelihood of returning.122 At the same time there are numerous examples of countries from which larger numbers of people have fled where remittances today account for a considerable share of GDP.123

Refugees may be both recipients and senders of such financial transfers: As recipient they may use the money to settle in the host country or to fund their onward migration; as sender they may support those who remained in the country of origin and contribute to expanding the economic activity of the population there. Transfers can thus play a role in strengthening the resilience of people and institutions in the states of origin. And they can encourage vulnerable population groups to remain in the home country. Remittances can also assist with reconstruction after violent conflict.124 They are especially relevant in such contexts because they flow even in situations where there is little prospect of investment.125

Financial transfers are often too expensive.

A closer examination of financial transfers to the ten most important countries of origin of refugees reveals how strongly the economic situation in the host country influences the level of remittances. Transfers from high-wage countries like Germany and middle-income countries like Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon are especially large. Whereas migrants generally possess well-established channels for remittances, it takes time to establish new transfer channels in refugee situations.126

If financial transfers are truly to assist refugees and internally displaced persons they must be secure and affordable. The World Bank and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) have published practical proposals for ensuring this.127 The German government has taken up these approaches, including through the online portal “Geldtransfair”, which was set up by the German Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). By enhancing transparency, the portal seeks to reduce transfer costs.128 The World Bank sees a need for action concerning pricing of financial transfers and great potential for reducing costs, especially in the most expensive transfer channels, for example to and within Sub-Saharan Africa.129

In general it must be remembered that international donors have no decisive influence on the level, timing or recipients of financial transfers. But the overall volume of remittances and their importance – especially in times of crisis – give an indication of the kind of reserves that could be tapped with affordable transfer structures.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Numerous financing instruments that could be of relevance in refugee situations are currently under discussion. Even if some of the approaches cannot yet be evaluated – because the data is inadequate or they are still under development – none of them can be expected to close the growing funding shortfalls in humanitarian aid and development cooperation on their own. What is needed is a combination of approaches – including existing instruments – that ensures that these forms of financing fulfil the efficiency criteria laid out above: They should (1) be transparent and enable accountability, (2) strengthen ownership and participation, (3) be effective in the longer term and (4) promote (or at least not hinder) the coordination of humanitarian aid and development cooperation.

If these criteria are applied to the financing instruments discussed above, the following points emerge:

-

In relation to transparency and accountability, blended finance, concessional loans and impact investing are highly suitable instruments, because their application is tied to events. All these instruments could be configured in such a way as to achieve clarity about the respective purpose, allowing corresponding evidence to be supplied. In order to improve accountability all financing instruments should be based on transparent and comparable needs analyses.

-

More ownership by recipients (both governments and individuals) can best be achieved through development grants, as well as remittances and the graduation approach; participation is fostered by remittances.

-

With respect to effectiveness and efficiency, development grants are recommended, while pooled funds also possess considerable potential if adequately configured, especially as they are accessible to local partners and permit a rapid and flexible response to acute crises. If refugees and host communities are to be supported effectively, the collection of socio-demographic data on refugees needs to be further improved, as proposed in the Global Compact for Refugees.

-

A closer connection between humanitarian aid and development cooperation can best be achieved through concessional loans, development grants and pooled funds, as long as that objective is also taken into consideration when the instruments are designed. In this context triangular partnerships between states, non-traditional donors (for example “Emerging Donors”) and private foundations can be promoted.

For the future funding of refugee assistance, three goals will be uppermost and demand political action:

(1) Secure permanent basis for public funding

Public funding will continue to be of crucial importance for refugee assistance. Currently support is largely provided in the humanitarian aid framework. That is not likely to change in any fundamental sense: future humanitarian emergencies will have to be addressed primarily through rapid acquisition of aid funds. Yet in view of the protracted nature of refugee situations it will be imperative to supplement short-term aid with longer-term support and more sustainable and predictable financial resources. In order to ensure this it would be very helpful if the OECD states were to fulfil their commitments to the 0.7-percent target. The German government could set a good example by increasing its funding for humanitarian aid and development cooperation to a point where the target can regularly be met. As the world’s second-largest donor of humanitarian aid and development cooperation, the German government should also ensure that funds for refugees and internally displaced persons are more needs-based, long-term, predictable and timely. This applies especially to contributions to UNHCR, which has very little unearmarked and multi-year funding available. UNHCR’s experience with regional appeals for acute refugee situations could serve as a model for flexible and innovative funding. Germany’s role as a major funder offers the German government – especially the Federal Foreign Office and the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development – the opportunity to work towards improving the collaboration between humanitarian aid and development cooperation, for example through closer geographical and sectoral coordination. And it allows the government to create incentives for organisations to collaborate more closely on the ground.

(2) Integrate short-term and longer-term aid

In the research there is a consensus that refugee assistance is especially effective and sustainable where it promotes self-reliance of refugees themselves and supports host communities. One (potentially rapid) route to strengthen self-reliance is direct payments, of which donor countries including Germany have made increasing use in recent years. With its relatively low transaction costs, cash-based assistance can expand the options open to recipients and relatively quickly strengthen local markets. Similar effects can also be achieved by micro-finance services. Greater use should be made of both forms of support, while paying systematic attention to sustainability. This applies especially to cash-based assistance, which is generally used as a substitute for or supplement to social security measures, but could certainly also be tied to vocational training initiatives. That would considerably enhance its effectiveness. Here too, financing must be sufficient, predictable, flexible and long-term.

(3) Strengthen European and international cooperation

Financing instruments that leverage private finance through public funds and guarantee instruments should be developed and implemented in the scope of European collaboration. The German government should review the pros and cons of these instruments and then decide whether it wishes to expand them in the context of the EU’s next Multiannual Financial Framework. In the case of concessional loans, the German government should expand its exchange and cooperation with the World Bank and regional development banks. Here it should be remembered that most host countries are critical towards funding approaches that tie aid funds to political conditions or provide funding as loans. Their governments often struggle to convince their own citizens that they should take out loans for refugees, especially where they are already heavily indebted and face growing economic and social burdens. The German government should therefore work to avoid these host countries being forced into borrowing.

Broadly speaking, many of the new financing instruments will remain ineffective without adequate intergovernmental and international cooperation. The German government should coordinate its refugee assistance closely with donors and orientate it on multilateral processes and good practice identified in the scope of those processes. Alongside the “Grand Bargain” and the obligations from the Aid Effectiveness Agenda, this means above all the Global Compact on Refugees. As well supporting the UNHCR’s core humanitarian mission, the German government should support UNHCR’s structural approaches and cooperation with development actors. This needs to go along with efforts to improve the available data, also through closer collaboration with the IOM.

The Global Refugee Forum established under the Global Compact on Refugees offers a promising framework for developing a catalogue of goals for the various sources of financing. The Compact also specifically states that the private sector should play a greater role. Targeted investment could contribute to conditions enabling refugees to contribute to economic development in their host countries – rather than simply being regarded as recipients of charity.130

In view of the diversity of funding approaches and their in some cases unclear effects the German government should use its newly established special committee on root causes of forced displacement (Fachkommission Fluchtursachen) to organise a systematic national and international exchange on experience with financing instruments. The findings could flow into a more comprehensive German government strategy for financing refugee assistance.

Abbreviations

|

BMZ |

German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung) |

|

CGD |

Center for Global Development (Washington, D.C.) |

|

CRRF |

Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework |

|

DAC |

Development Assistance Committee |

|

DEval |

Deutsches Evaluierungsinstitut der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit |

|

DIE |

German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik |

|

EBRD |

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

|

EFSD |

European Fund for Sustainable Development |

|

EIB |

European Investment Bank |

|

EIP |

External Investment Plan |

|

EUTF |

European Union Trust Fund for Africa |

|

GCFF |

Global Concessional Financing Facility |

|

GIZ |

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit |

|

GNI |

gross national income |

|

IASC |

Inter-Agency Standing Committee |

|

IDA |

International Development Association |

|

IOM |

International Organisation for Migration |

|

KfW |

Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau |

|

OCHA |

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

|

ODA |

Official Development Assistance |

|

OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

|

SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

|

SMEs |

small and medium-sized enterprises |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

|

UNRWA |

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East |

Endnotes

- 1

-

Steffen Angenendt, David Kipp and Amrei Meier, Gemischte Wanderungen: Herausforderungen und Optionen einer Dauerbaustelle der deutschen und europäischen Asyl- und Migrationspolitik (Gütersloh, 2017), http://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/Projekte/Migration_fair_gestalten/

IB_Studie_Gemischte_Wanderungen_2017.pdf (accessed 6 June 2019). - 2

-

UNHCR, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2018 (Geneva, 2019), 2f., http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/

5d08d7ee7/ unhcr-global-trends-2018.html (accessed 27 June 2019). - 3

-

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Mid-Year Trends 2018 (Geneva, 2019), 5, https://

www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5c52ea084/mid-year-trends-2018.html (accessed 25 February 2019). - 4

-

UNHCR, Global Trends 2018 (see note 2), 2.

- 5

-

Ibid., 15, 23.

- 6

-

Ibid., 27–33.

- 7

-

UNHCR, Global Trends 2018 (see note 2), 33.

- 8

-

Nita Bhalla, “Ethiopia Allows Almost 1 Million Refugees to Leave Camps and Work”, Reuters, 17 January 2019.

- 9

-

On the definition of fragility, see World Bank Group, Maximizing the Impact of the World Bank Group in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Settings (Washington, D.C., March 2018), 6, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/855631522172

060313/pdf/124654-WP-PUBLIC-MaximizingImpactLowres

FINAL.pdf (accessed 25 February 2019). - 10

-

Ibid., 3f.

- 11

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), States of Fragility 2018 (Paris, 2018), 99.

- 12

-

Lili Mottaghi, Refugee Welfare: A Global Public Good, MENA Knowledge and Learning Quick Notes 167/2018 (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, April 2018), 4, http://bit.ly/2RUVt2r (accessed 15 March 2019).

- 13

-

Steffen Angenendt, Marcus Engler and Jan Schneider, European Refugee Policy: Pathways to Fairer Burden-Sharing, SWP Comment 36/2013 (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft Politik, November 2013), 4f., http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/

contents/products/aktuell/2013A65_adt_engler_schneider.pdf (accessed 25 February 2019). - 14

-

Steffen Angenendt and Anne Koch, Der Globale Migrationspakt im Kreuzfeuer: Trifft die Kritik zu? SWP-Aktuell 69/2018 (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, December 2018), https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/der-globale-migrationspakt-im-kreuzfeuer/ (accessed 11 June 2019).

- 15

-

Steffen Angenendt and Nadine Biehler, On the Way to a Global Compact on Refugees: The “Zero Draft”: A Positive, but Not Yet Sufficient Step, SWP Comment 18/2018 (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, April 2018), https://www.swp-berlin.

org/en/publication/on-the-way-to-a-global-compact-on-refugees/ (accessed 29 August 2019). - 16

-

Background discussions with representatives of international organisations, Berlin and Geneva, February and March 2019.

- 17

-

Harriet Grant, “UN Agencies ‘Broke and Failing’ in Face of Ever-growing Refugee Crisis”, Guardian, 6 September 2015.

- 18

-

High Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing, Too Important to Fail – Addressing the Humanitarian Financing Gap (New York, January 2016), 2f., http://bit.ly/2XKMjLd (accessed 25 February 2019).

- 19

-

UNHCR, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Part II: Global Compact on Refugees, A/73/12 (Part II)/ 2018 (New York, 2018), 6–7 (para. 32), http://www.unhcr.

org/gcr/GCR_English.pdf (accessed 26 October 2018). - 20

-

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Grand Bargain (Hosted by the IASC) (Geneva, 2017), https://interagencystanding

committee.org/grand-bargain-hosted-iasc (accessed 11 October 2018). - 21

-

High Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing, Too Important to Fail (see note 18), 2.

- 22

-

Without the appeals of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), see Development Initiatives, Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2018 (Bristol, 2018), 27, http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/

06/GHA-Report-2018.pdf (accessed 16.8.2018). - 23

-

UNHCR, Update on Budgets and Funding for 2018 and 2019 (4 March 2019), 1, https://www.unhcr.org/5c7ff3484.pdf (accessed 6 June 2019).

- 24

-

Idem, Update on Budgets and Funding for 2017 and 2018 (26 February 2018), 1, https://www.unhcr.org/5a9fd8b12.pdf (accessed 14 February 2019).

- 25

-

A new “migration” code introduced in 2018 records support provided in connection with development-related migration policy. An established “emergency aid” code already recorded humanitarian aid to all groups including refugees.

- 26

-

Kathleen Forichon, Financing Refugee-hosting Contexts: An Analyis of the DAC’s Contribution to Burden- and Responsibility-sharing in Supporting Refugees and Their Host Communities, OECD Development Cooperation Working Paper 48/2018 (Paris: OECD, December 2018), 9, http://bit.ly/2JlzIoK (accessed 14 February 2019).

- 27

-

OECD, Development Co-operation Report 2018: Joining Forces to Leave No One Behind (Paris, 2018), 272f., http://bit.ly/2LB4r3V (accessed 28 February 2019).

- 28

-

Development Initiatives, Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2018 (see note 22), 30.

- 29

-

Turkey claims to have spent about $35 billion on refugees between 2011 and 2018, but does not say how it arrived at the figure. See Sevil Erkuş, “Migrants Day: Turkey Hosts Largest Number of Refugees in the World”, Hürriyet Daily News, 18 December 2019, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/

migrants-day-turkey-hosts-largest-number-of-refugees-in-the-world-139803 (accessed 6 June 2019). - 30

-