EU Global Health Policy

An Agenda for the German Council Presidency

SWP Comment 2020/C 12, 09.03.2020, 4 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2020C12

Research AreasIn the second half of 2020, Germany will take over the Council Presidency of the European Union. It will form a presidency trio with Portugal and Slovenia, who will succeed Germany in 2021. The Federal Government should use its presidency to strengthen the EU’s role in global health policy. The EU has so far focused primarily on (infectious) disease prevention and control as it has most recently in response to the coronavirus outbreak (Covid-19). However, in order to contribute to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, it should focus more comprehensively on health systems. This would require an intersectoral and preventive approach at EU level, opening the door to coherent collaboration, alliances and a people-centered policy in line with European values.

The European Commission makes an indirect contribution to improving health through its role in the EU. It complements the policies of Member States. The Commission is also directly committed to the goals of global health. This includes striving to improve the health of people worldwide, reducing inequalities and ensuring protection against global health threats. According to EU Council Conclusions from 2010, this involves making global health part of EU foreign and development policy as well as cooperating with third countries and international organisations. The EU’s role in health policy is currently being challenged on the international stage due to Brexit. In 2016, the UK provided around 12 percent of the EU’s Overseas Development Assistance budget. To make matters worse, the EU has lost London’s ability to influence global health policy; joint health research must be renegotiated.

Legal options for action

The Council set out the objectives of the EU’s global health policy in its conclusions from 2010:

-

To reduce global health inequalities by supporting countries to achieve universal and equitable coverage of essential health services

-

To adopt an “Equity and Health in All Policies” approach

-

To focus not only on development policy, but also on trade, migration, security, food security, research, environment and climate.

Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU affirms the Union’s responsibilities on global health policy. Accordingly, any international action taken by the EU on health issues must be based primarily on two rationales: the human right to health for everyone everywhere and the security of the health of the European population. Ideally, the two approaches would complement each other. However, they can also be a hindrance if health protection measures do not take human rights implications into account. According to Article 3 of the Treaty on the EU, European and global interests, such as the enforcement of human rights and sustainable development, should also be promoted worldwide.

One, two, many global EU health policies

Few EU countries have developed their own global health strategies. The UK was the first country to test the water in 2008. Germany published its initial concept in 2013, followed by France in 2017 among others. In addition to the focus on infectious disease control, these two countries also prioritised strengthening health systems. Sweden’s strategy was published in 2018, following the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and a high-level conference on the Economy of Wellbeing took place in 2019 under the Finnish EU Council Presidency.

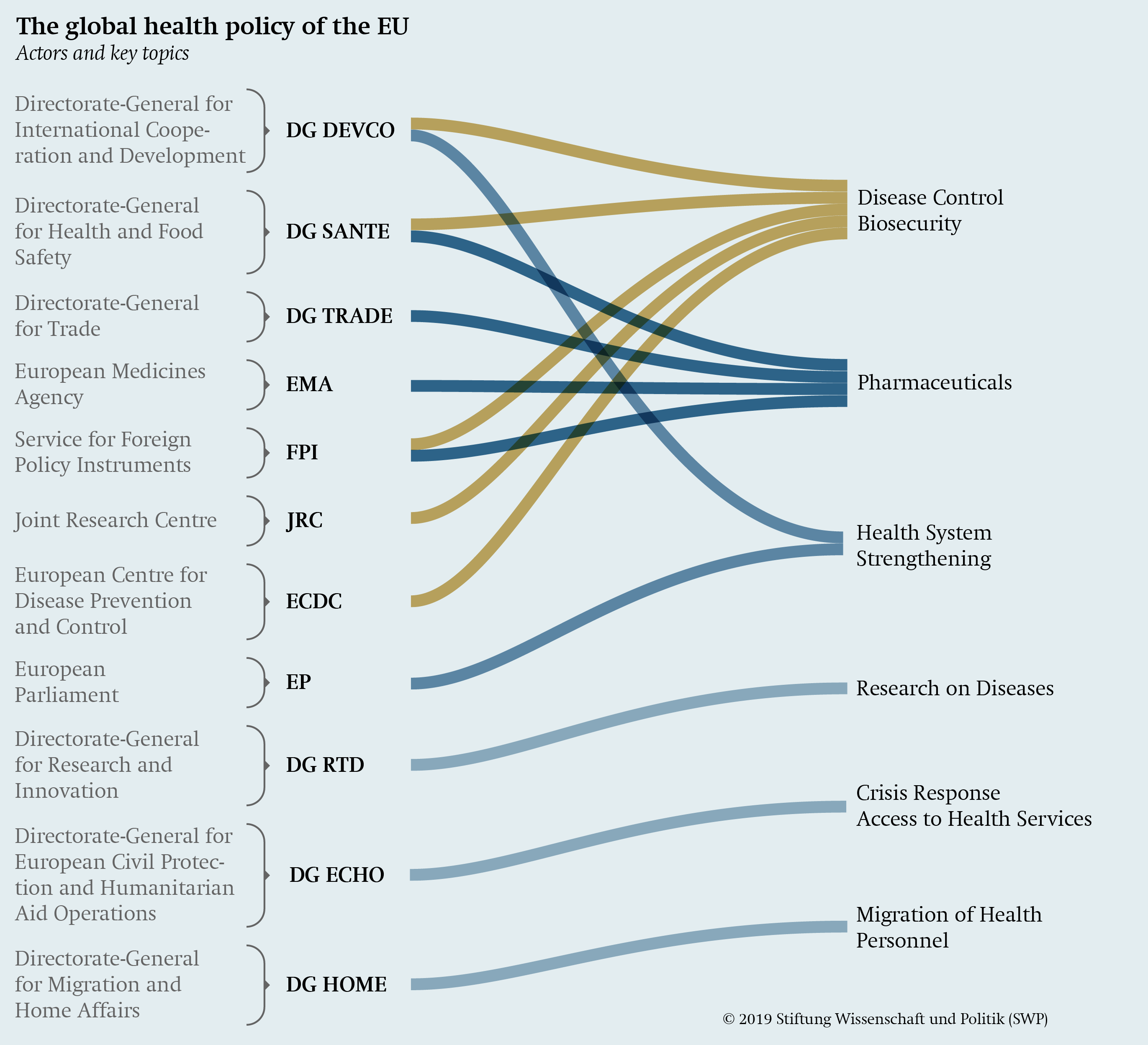

The EU does not yet sufficiently incorporate sustainable development into its global health policy. This is evident from the key topics listed by EU institutions for global health (see diagram). Many actors focus their external policies on researching and treating diseases. This is also evident in their current efforts to contain the spread of Covid-19. Brussels coordinated the repatriation of almost 500 EU citizens and had protective equipment delivered to China as part of its Civil Protection Mechanism. At the same time, the EU has provided EUR 242 million for research and to shore up global preparedness, prevention and mitigation.

There is no direct link between trade and health at EU level. While the Directorate-General for Trade is concerned with access to medicines, it has little regard for the negative impact of low tariffs on harmful goods such as tobacco. And despite the EU’s Health in All Policies approach, the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the Directorates-General for Environment and Climate seem to have scant regard for global health. In the event of emergencies, such as the Covid-19 outbreak, and even beyond the EEAS could pool the efforts of the Brussels’ directorates and agencies and serve as a contact point for affected countries. This would represent a coordinated division of labour at European level in the field of global health; the establishment of the European corona response team is a good start.

Challenges for the EU

The objective of harmonising global health policies poses challenges for the EU that compromise their visibility, effectiveness and needs-based focus. As indicated by Eurostat, the Global Health Expenditure database, and the current World Health Organization (WHO) European Health Report, there are significant differences between EU countries on healthcare funding and quality. In terms of government spending on health, Germany is in second place behind France with around 11 percent of GDP; Romania is last place with just over five percent – comparable with Kenya and Myanmar. At the same time, health inequalities influence how externally credible and assertive the EU is in this field.

For the EU reducing inequalities internationally is made even more difficult because some Member States retain a strong focus on controlling selected diseases while neglecting the social, commercial and ecological determinants of health. As a result, there is much greater demand now for approaches to health systems that include preventive and health-promoting measures as well as disease control. The current case of Covid-19 highlights clearly the need for these measures. Brussels’ development policy could provide more measures to relieve the burden on China, its neighbours and countries with weak health structures in general.

The overall challenge for the EU is to make its policies more systemic and coordinated, and to better integrate areas such as trade or climate with an approach that focuses on health promotion, health protection and disease prevention.

Untapped EU potential

The EU can potentially do more, particularly at the financial, substantive and multilateral level. Its multiannual financial framework ensures it has medium-term planning security. Since the impact and success of a global health policy can usually only be measured a long time after it has been implemented, continuity is crucial. Substantively, the EU will have a much broader scope of action than other health-related organisations because it deals not only with health, but also with all other policy areas. The EU can bring its political expertise to bear through its international channels in the health sector; like the German government, it sits on the administrative board of one of the most financially powerful global health institutions, the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. At their next meeting in May, the EU could assert its political influence, together with EU Member States, and advocate systemic and intersectoral approaches. At the same time, the EU maintains multilateral contacts, for example, as part of its partnership with the African Union (AU), which it could also use to promote its global health agenda.

Recommendations for Germany’s EU Council Presidency

Greater commitment is needed to meet the European ambition of pursuing global health policies in an effective and equitable manner. Germany can make a contribution to the UN Agenda 2030 by prioritising the topic of global health during its Council Presidency. The following factors could be useful:

-

Mainstreaming global health: In Brussels, health could be better linked with other policy areas if inter-ministerial coordination in Germany would take place prior to its Presidency. By coordinating at the national level, global health can be introduced to the relevant Council working groups (on health, development cooperation, trade, human rights, among others). On trade, for example, it would be possible to integrate health into the sustainability chapters of trade agreements by requiring binding sustainability impact assessments. It might be helpful to reactivate the Global Health Policy Forum in order to exchange information between relevant sectors and actors.

-

Update of Council Conclusions: The 2010 Council Conclusions should be updated in order to link EU global health policy to the Decade of Action to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Germany could propose developing a roadmap which would include review and follow-up mechanisms.

-

OECD Health Categories: In order to identify developments and gaps in today’s global health policy, there is a need for a system of categories for recording national and international health spending that outlines the dimensions involved in strengthening health systems. In order to achieve this, Germany could cooperate with the WHO and OECD and provide the impetus to adapt the current system of categories to meet WHO standards and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

-

Partnerships: The EU should establish international partnerships to strengthen its soft power in the global health sector. Joint positions could be developed with the African Union and platforms, such as the annual EU-AU Human Rights Dialogue. These could be used, in particular, to highlight health issues for development policy. Together with European and African partners, Germany could also set the tone here for the narrative of the next AU-EU summit which is scheduled to take place at the end of 2020.

-

Parliamentary participation: When Germany takes over the Council Presidency, the Bundestag will become a presidential parliament. This parliamentary dimension could be used to include global health in interparliamentary events.

Germany could view its trio presidency with Portugal and Slovenia as a long-term opportunity. Its goal would be a harmonised, strengthening of equitable health systems as a feature of value-based action at the European level. The EU could use the topic of health to increase both its soft power on the diplomatic stage and its hard power in areas such as trade.

Susan Bergner and Maike Voss are Associates in the Global Issues Division at SWP. Both work in the “Global Health” project, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2020

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN 1861-1761

doi: 10.18449/2020C12

Translation by Martin Haynes

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 15/2020)