Divided But Dangerous: The Fragmented Far-right’s Push for Power in the EU after the 2024 Elections

SWP Comment 2024/C 44, 01.10.2024, 8 Pagesdoi:10.18449/2024C44

Research AreasFar-right forces emerged strengthened following the 2024 European Parliament elections. Nonetheless, they still remain divided within the legislative body. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) made moderate gains and is now joined by the Patriots for Europe (PfE) and Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) groups. Although the alliance of France’s National Rally and Hungary’s Fidesz has made the PfE the third-largest group in the Parliament, its direct influence is likely to remain limited. After all, the core interest of the PfE and its members is more focused on funding, publicity and national arenas. The biggest prize, however, is influence in the Council and European Council, where the PfE hopes to gain more direct say via national governments. This could have a lasting impact on European politics, however, it is less likely to affect members of the EP.

One of the issues that dominated the run-up to the 2024 European Parliament (EP) elections – as in 2019 and 2014 – was the expected political rise of the right. However, the election results were more nuanced, resulting in new avenues of influence of these parties on European politics and policy-making both within the European Parliament and the wider institutional setup of the EU.

Three developments are of particular note here: First, far-right parties made the most significant gains in the EU’s founding states. In France, the National Rally (NR) won most of the country’s seats in the EP; in Germany, Alternative for Germany (AfD) won almost 16 per cent of the vote (compared to 11 per cent in 2019); in Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy more than quadrupled its share of the vote to 28.8 per cent (after 6.44 per cent in 2019), although its coalition partner, the more right-wing Lega, suffered major losses. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) won 17 per cent. Other notable gains were made by the Bulgarian Revival party and the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), which won the most votes in the Austrian EP elections. Because Germany, France and Italy, as the most populous EU states, have the most seats in the EP, the gains made by these parties are particularly significant.

The second notable development arising from the 2024 EP elections is the more nuanced picture that arises when looking at the EU as a whole. In Finland, Sweden, and Hungary, far-right parties lost support compared to 2019. In many Central and Eastern European countries, including Czechia, Estonia and Poland, 2024 gains were also limited. A comparison of the 2019 and 2024 EP election results shows, above all, that the most significant gains for the far-right parties already occurred in 2019.

The third development arising from the 2024 EP elections is the qualitative difference in public discussions, as, for the first time, the centre-right openly discussed under what conditions it should cooperate with far-right parties. The European People’s Party (EPP) defined three criteria for cooperation with (parts of) the national conservative European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), namely, they must be pro-EU, pro-Ukraine and pro-rule of law. These criteria were primarily directed at exploring cooperation with Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, but excluded parties that were further to the right. In contrast, the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D), the liberal Renew Europe group, and the Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens-EFA) all rejected cooperation with all right-wing parties, including the ECR. Furthermore, these three political groups also made it clear that they would not cooperate with the EPP if it was to collaborate with far-right parties, starting with the election of the European Commission President. After relatively short negotiations, Ursula von der Leyen was able to build a majority to be re-elected as Commission President with the support of the EPP, S&D, ALDE and the Greens-EFA, thus not requiring the backing of Meloni or the ECR.

Fluid political groups of the European Parliament

The composition of the EP and its majorities also depends on how national members of the European Parliament (MEPs) organise themselves into political groups. The elected representatives usually agree on the formation of these groups prior to the EP’s inaugural session as important positions in the Parliament, such as committee chairs, heads of delegations and the President of the Parliament, are allocated according to the size of the respective groups. However, MEPs can switch between groups at any time, and they do so much more frequently than at the national level.

This phenomenon is exemplified in the most recent 2019–2024 Parliament: The EPP, the largest and most well-organised group, gained 12 new MEPs during the last legislative period, seven of whom previously belonged to one of the far-right groups. It also lost 19 MEPs, 11 of whom pre-emptively left the EPP because their Fidesz party was expected to be expelled from the group in March 2021. In contrast, the liberal Renew Europe group can be seen as a catch-all actor, having absorbed a total of ten MEPs from four different groups (the ECR, EPP, Greens-EFA and S&D) over the course of the 2019–2024 period. Nevertheless, the centre-left and centre-right groups have now existed in their current forms for several parliamentary terms (see SWP-Studie 9/2019).

The most significant shifts have been and continue to be in the fragmented spectrum to the right of the EPP. In the 2019–2024 period, the far-right populist Identity and Democracy (ID) group stood further to the right of the ECR. Even before the 2024 European elections, however, it was clear that there would be major shakeups in the 2024–2029 period. In response to several scandals involving the AfD’s lead candidate, Maximilian Krah, the party was expelled from the ID group at the behest of NR President Marine Le Pen. At the same time, Viktor Orbán, whose Fidesz party has been unaligned since 2021, publicly sought to join either the ECR or ID; in Orbán’s view, the best-case scenario would be to merge these two groups, along with his Fidesz.

Limited restructuring

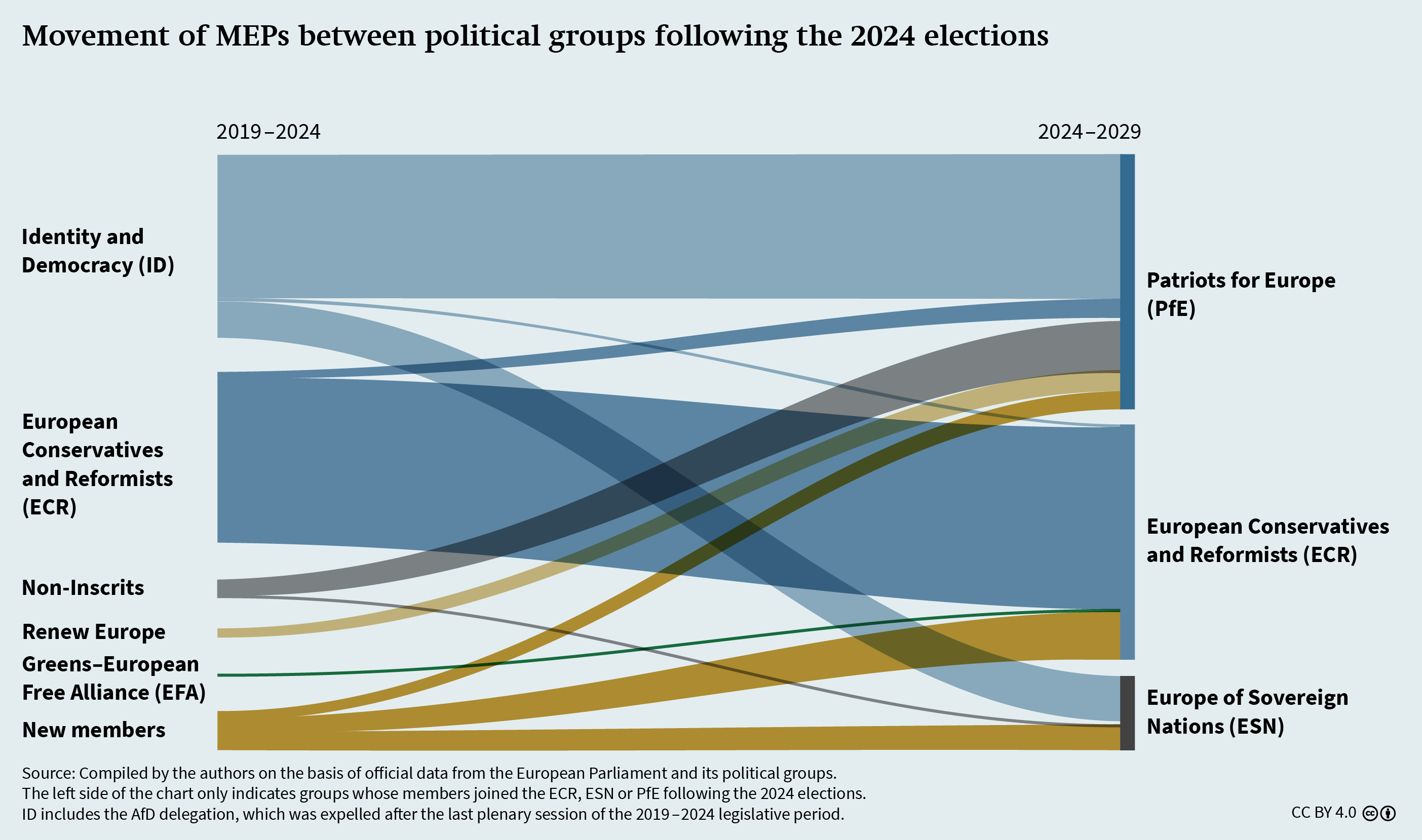

Following weeks of speculation about changes in the setup of far-right groups in the EP, two new parliamentary groups were finally formed whereas the old ID group ceased to exist (see Figure). In its place came the right-wing nationalist Patriots for Europe (PfE) and the right-wing populist – or extremist – Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN). While PfE is nearly identical to its predecessor (the ID), the ESN was co-founded by the AfD, which was expelled from the ID.

Superficial stability in the ECR

The ECR, having existed since the EP’s 2009–2014 legislative period, has proven to be relatively stable. This is particularly true when considering that no other far-right group founded alongside the ECR has survived more than one parliamentary term. Born out of a cooperation of the UK’s Conservative Party under then-Prime Minister David Cameron, Poland’s Law and Justice party (PiS) and Czechia’s Civic Democratic Party (ODS), the ECR was the third-largest group in the 2014–2019 legislature, comprising 77 MEPs; yet, by the end of the 2019–2024 period, it was only the fifth-largest group. After some reshuffling, it is now the fourth-largest group, behind the newly formed PfE. Following the departure of the Tories from the EP in the wake of Brexit, the ECR group was subsequently dominated by the PiS, with Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy initially holding the role of junior partner in the last legislature. However, since its success in the Italian parliamentary elections, and certainly following the 2024 EP elections, it has clearly come to dominate the ECR, both in terms of numbers (24 MEPs) and policy. Other than the Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala’s ODS and the Brothers of Italy, other ECR member parties are coalition partners in governments (Croatia and Finland) and supporters of a minority government (Sweden).

Despite its relative stability, the ECR experienced several shifts in the 2014–2019 and 2019–2024 legislative periods, which changed its numbers and composition. The ECR started the 2014–2019 legislature with 70 MEPs and ended it with a net gain of seven MEPs, despite the loss of the AfD delegation. This gain was mainly the result of new members from the EPP group, including Italian MEPs who switched from Forza Italia to the Brothers of Italy, and the controversial entry of the right-wing nationalist Sweden Democrats party. During the 2019–2024 parliamentary term, the ECR also grew, from 62 MEPs at the beginning to 69 at the end. This was again mainly due to Italian MEPs switching to the Brothers of Italy (six in total), but also due to the Finns Party’s re-entry to the group, which left the ID group when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022.

As of the beginning of the 2024–2029 legislative term, the ECR’s 78 MEPs come from a total of 23 national delegations, 11 of which were already members of the ECR in the previous term, whereas nine come from parties that have either been newly elected or had not previously belonged to a political group. Once a part of the Greens-EFA group, the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union joined the ECR, and one Estonian MEP switched from the ID to the ECR.

Overall, the ECR continues to be characterised by a high degree of continuity in terms of its constituent delegations from Italy, Poland and, to some extent, Czechia. It is especially viable in terms of the net number of its MEPs when compared to the now dissolved ID group. However, it is also largely comprised of very small and new national delegations. Less than half of the national delegations have more than two MEPs. It is therefore expected that the group will face fluctuations and difficulties in coordinating the many small delegations in the current legislature.

Patriots for Europe (PfE): a new alliance centred around Orbán and Le Pen

Arguably the most surprising development in this context took place in June 2024, when Hungary’s Fidesz, Austria’s FPÖ and Czechia’s Yes party (ANO) joined forces to present the founding document of the Patriots for Europe. In their manifesto, the authors describe a Europe that they believe to be dominated by non-transparent institutions and illegitimate bureaucrats whose ultimate aim is to replace the Europe of nation states with a “European superstate”. In their view, in the spirit of the supposedly genuine Europe of nations, the institutions need to be reconquered and European politics fundamentally reoriented in order to restore the sovereignty of the nation states. In addition, they primarily focus on their desire to significantly limit migration and unconditionally preserve what they see as Europe’s fundamental Judeo-Christian heritage.

The now third-largest group in the EP is primarily made up of national delegations from the dissolved ID group; this does not include Germany’s AfD, which was expelled from the ID shortly before the election, or Czechia’s far-right Freedom and Direct Democracy party (SPD). From other groups, the PfE was able to win over Czech politician Andrej Babiš’s ANO party, which had left the liberal Renew Europe group, and the Spanish Vox party, which came from the ECR. From the parties newly elected to the EP, Portugal’s Enough! party (Chega!), which has been strengthened at both the national and European levels, the Latvia First party, Greece’s Voice of Reason party, and Czechia’s Oath and Motorists’ electoral alliance, directly joined the PfE.

Dominant national delegations in the PfE over the next few years are likely to be France’s NR (30 MEPs) and Hungary’s Fidesz (11 MEPs), especially since Viktor Orbán will have a direct vote in the European Council. Italy’s right-wing League party (Lega), which once set the tone in the ID, suffered heavy losses, losing 14 seats (from 22 to 8), and will need to pass the baton to the NR.

With 83 current members, the PfE is considerably stronger than the ID group was during the 2019–2024 legislature, when it comprised 59 members before the expulsion of the AfD. Unlike the ECR, the PfE consists of only 13, on average relatively large, national delegations, which could simplify internal coordination. Furthermore, within the old ID group, differences in the foreign and security policy ideas of France’s NR on the one hand and Italy’s Lega on the other were particularly poignant: While Lega adopted a deliberately constructive approach in the last legislature, the NR adopted a decidedly anti-Western stance, rejecting support for Ukraine (see SWP Comments 8/2024). With the weakening of Lega and the inclusion of a Fidesz that is just as anti-Western as the NR, the pendulum is likely to swing in favour of Marine Le Pen and Viktor Orbán.

It remains to be seen whether the PfE, unlike the former ID, will be more than a strategic alliance and present a more united front in the EP. While of the former ID parties only Lega had been part of a national government, the PfE is still close behind the ECR in this respect – with Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz now leading a government and Geert Wilders’ PVV being a part of the governing coalition in the Netherlands as of July 2024.

Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) as the fundamental opposition

After it was expelled from the ID, the AfD delegation succeeded in building the ESN group around itself. The so-called Sofia Declaration of April 2024 is generally regarded as its founding document. Similar to the PfE’s manifesto, it invokes the narrative of the “dictatorship of an unelected [EU] bureaucracy” that would undermine the national sovereignty of member states and, from the ESN’s perspective, bring about an existential crisis to Europe and threaten its values. Its platform issues are reducing bureaucracy, rolling back the alleged influence of multinational corporations and starting peace negotiations to end the war in Ukraine. Considering that the PfE’s manifesto and the ESN’s Sofia Declaration are very similar in their objectives and wording, the true political divisions between the PfE and the ESN are blurry.

It is expected that the AfD delegation will dominate the ESN in terms of both policy and personnel in the current 2024–2029 legislative session, in large part because 14 of the group’s 25 total representatives come from the AfD. The political spectrum represented within the ESN is very broad: It hosts members from France’s right-wing conservative Reconquest party, Hungary’s Our Homeland Movement party (which is considered far-right and revisionist even in Orbán’s Hungary), Bulgaria’s ultra-nationalist Revival party, and Czechia’s SPD (which openly advocates for Czechia’s exit from the EU). Against this backdrop, the ESN currently seems to be a catch-all for those right-wing MEPs who, for various reasons, have not joined the ECR or PfE. At the same time, only three of the ESN’s eight national delegations (namely, those from Bulgaria, Germany and Poland) have more than one MEP in the group. Any serious policy initiatives would therefore have to be built on co-leadership from the German and Polish far-right parties.

Nonetheless, the question of whether or not to continue supporting Ukraine in its war with Russia could prove to be a particularly divisive issue in this newly constituted group. Whereas the AfD together with the Bulgarian, Slovakian and Hungarian delegations are Russia-friendly and critical of further support to Ukraine, the Polish and Lithuanian delegations (4 MEPs in total) share the national perception of Russia as a direct threat and are more inclined to support aid to Ukraine. However, the maintenance of political harmony within the group is particularly important due to the fact that the ESN houses 25 MEPs from eight member states, just above the minimum 23 MEPs from seven member states that is required to maintain group status. So far, none of the ESN parties are part of their national governments.

Potential to influence EU policy

Political groups give their national delegations decisive advantages in key functions of the European Parliament. This applies in particular to the allocation of key positions, such as the appointment of committee chairs or rapporteurs, which are central to the legislative process. Although the non-aligned MEPs (Non-Inscrits) can also nominate joint candidates to these roles, their probability of actually being appointed is low.

If the PfE and ESN had hoped that forming new groups would give them access to these top positions, however, they were wrong. In the beginning of the parliamentary term, central positions are allocated in principle according to the size of the groups. In practice, the allocation is still subject to a vote. Although the PfE is the third-largest group, the majority of the EP denied it representation in the Bureau and granted it no committee chairs. The same applies to the ESN. The ECR, on the other hand, was not included in this cordon sanitaire. Politicians from the ECR were elected to two vice-president positions in the Bureau and three committee chairs, including in the important budget and agriculture committees. In addition to holding more weight when it comes to appointing top officials, political groups enjoy other advantages over Non-Inscrits MEPs. For example, they have a greater ability to decide on the allocation of speaking time and are more likely to be able to present questions to the European Commission for oral answer. In addition, the political groups have significantly more financial resources and greater autonomy in the use of funds allocated to them from the EP budget.

Although the ECR did not participate in the re-election of von der Leyen to the presidency of the European Commission, it could still increase its political and institutional influence in the current parliamentary term if it presents itself as an acceptable partner to the EPP. The PfE, on the other hand, has increased potential to influence negotiations in the European Council and the Council of the European Union. One reason behind the foundation of the PfE could indeed be the group’s aim to gain access to the levers of EU power via the Council. In contrast to the old ID group, of which only Lega was part of a government, the PfE leads the government in Hungary via Fidesz and in the Netherlands, the PVV is the largest party of the coalition (even if the prime minister’s party is politically neutral). Three further PfE parties, the FPÖ, ANO and Vox, aspire to become parties of government after their next respective national elections. In the medium term, this could decrease the degree of Viktor Orbán’s isolation in the European Council and allow him to expand his influence.

Fragility of the Cordon Sanitaire

Although far-right groups in Europe are fragmented, their reconfiguration in the new EP will be a key challenge for the mainstream parties. Ultimately, the EU’s ability to act and its political orientation will be strongly affected. Three strategies meant to meet this challenge have emerged:

The first strategy is maintaining a clear separation between the far-right and the more pro-EU factions. Major political decisions will likely still require support from the pro-European centre majority in the EP, in which the far-right groups are not involved. However, the re-election of von der Leyen as European Commission President (who won 401 of the minimum 360 votes) required the support of four groups – whereas three were enough in 2019, and two in 2014. In the European Council, governments led by far-right parties (under Giorgia Meloni (Italy, ECR) and Viktor Orbán (Hungary, PfE) abstained or voted against the nomination of von der Leyen; by contrast, the Czech government led by Prime Minister Petr Fiala, whose party belongs to the moderate wing of the ECR, voted in favour. Other national governments involving far-right parties, such as those of Finland and the Netherlands, also voted in favour of von der Leyen.

The second emerging strategy to deal with the far-right is a differentiated cordon sanitaire within the work of the EP. The ECR already received vice-president positions in the EP and committee chairs, and is expected to be granted rapporteur positions according to its relative size; the PfE and ESN, on the other hand, are likely to be kept out. Within the EPP in particular, there are growing calls for cooperation with the ECR in order to form majorities. In the current parliament, however, the EPP and ECR still would not be able to organise their own majority without the PfE or ESN, even if they included the Renew Europe group, with whom they overlap on economic policy. In this respect, the ECR does not yet play the role of ‘kingmaker’ among the right-wing groups. In a first exception to this rule, however, in September 2024 a centre-right to far-right majority spanning from EPP to ECR all the way to the PfE and ESN voted in favour of a (non-binding) resolution on Venezuela, against all other parties. This was celebrated by the PfE as a rejection of a cordon sanitaire and proof of a potential full right-wing majority.

Reorganisation among and within the far-right groups can be expected during the current term. It is entirely possible that they could merge or that one or more of them will collapse or further splinter. The ECR is likely to remain the most stable among them, while the ESN is the most precarious. Given its composition, the PfE is unlikely to be more united than the former ID group, which was rarely more than an alliance of convenience.

Far-right influence in the Council

The third strategy recognises that the cordon sanitaire is particularly fragile in the Council of the European Union and the European Council, where national governments negotiate compromises regardless of their partisan compositions. Therefore, this strategy promotes pragmatic engagement with governments led by or including extreme right-wing parties. In 2000, 14 of the then 15 EU member states declared that they would “not promote or accept any bilateral official at the political level with an Austrian government integrating the FPÖ”. Those days are long gone. Today, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is generally accepted as a key political player at the EU level, as well as in bilateral relations, including by Germany. The reaction of national EU governments to the formation of a Dutch government led by the PVV (PfE, formerly ID) has been largely pragmatic. After internal deliberations, the majority of the Renew Europe group also decided not to sanction their Dutch member, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), even though it supported the coalition government negotiated under the leadership of Geert Wilders.

When the Council of the European Union makes decisions that require unanimity, governments led by or including parties from the ECR and PfE now have a say and can veto, for instance important foreign and security policy initiatives. As noted above, constituent parties of the ESN are not yet part of any national governments. Nonetheless, the far-right is also close to being able to attain a blocking minority in qualified majority votes in the Council. Doing so requires at least four national governments representing 35 per cent of the EU population. Governments with ECR and/or PfE participation currently account for only 26.1 per cent. If far-right parties were to gain seats in one large member country (e.g. France or Spain) or several medium-sized ones, they could constitute a blocking minority and thus have decisive influence even over majority decisions. However, a closer look at past EP legislatures shows that open blockades in the Council of the European Union and the European Council, even by right-wing governments, are extremely rare. Most decisions are made by reaching a consensus and open confrontation is avoided. The EU has ways of effectively dealing with blocking member states, for example by linking decisions to packages or by engaging in selective cooperation in a way that excludes the blocking states. However, these tactics have only been tested with a small number of veto holders; if the number of far-right governments increases, the effectiveness of these strategies is likely to decrease. That still means that governments including far-right parties can be expected to co-shape all major EU legislation.

Consequently, the extent of the influence of far-right parties within European politics will not be decided in the EP. In terms of citizens’ votes, majorities that depend on the support of far-right parties are likely to remain rare in the coming legislature. Even if it becomes more difficult to form a majority when voting on controversial proposals, the ability of the EP to act will not be threatened by the gains or fragmentation of the far-right this term.

The strategic challenge for mainstream parties, especially those on the centre-right, can be formulated as follows: the more they try to maintain the cordon sanitaire vis-à-vis the ECR and vis-à-vis governments in which PfE parties participate, the more they encourage rapprochement between the ECR, PfE and ESN. At the same time, there are a growing number of parties within the EPP that are forming coalitions with far-right parties in their own countries, and they are promoting this at EU level. For their part, the far-right groups may seek to continue to exploit their already well-cultivated narrative of victimisation and perpetuate their portrayal of an ‘EU elite’ that is denying them access to institutional and financial opportunities. However, increased involvement of the ECR in the EP has the potential to further splinter the far-right; at the same time, the ECR’s increased acceptance normalises its policies and blurs the boundaries of the far-right. How the EPP parties manage this balancing act will largely determine the degree of influence that the far-right parties will have in the EP and beyond.

Max Becker is Research Assistant in the EU / Europe Research Division at SWP. Dr Nicolai von Ondarza is Head of the EU / Europe Research Division at SWP.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C44

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 46/2024)