The political debate over implementing qualified majority voting (QMV) into the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is of high political relevance, especially given the shifting geopolitical landscape in Europe, including Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and uncertainties regarding the US’s engagement post-2024 elections. Germany, along with a group of other EU member states, is leading efforts to integrate a “sovereignty safety net” within the CFSP framework. This initiative is designed to ease the concerns of reluctant member states, by providing enhanced veto options for matters affecting national interests. Moreover, mechanisms like constructive abstention and the “passerelle clause” could be further exploited to facilitate common CFSP actions without requiring treaty reforms. Nonetheless, it is crucial that all measures designed to build political consensus for expanding the use of QMV within the CFSP, strike the right balance between national interests and European solidarity. This balance is essential for strengthening the EU’s resilience and operational capability. Cyber foreign and security policy, with its transnational nature and need for swift and unified responses, presents a favorable testing ground for this approach.

There is ongoing political debate over the introduction of QMV into the CFSP since its entry into force in 1993. The evolving geopolitical context and security situation in Europe underscores the need for a more effective and efficient CFSP. Yet, the stance of the EU member states towards a supranationalisation of European foreign and security policy has not significantly changed. Since May 2023, Germany is leading a group of member states in facilitating the introduction of QMV within the CFSP. Members of the Group of Friends include Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Slovenia and Romania, with Ireland, Slovakia and the EEAS acting as observers. The discussion currently focuses on defining a so-called sovereignty safety net within the CFSP following the transition to QMV, which would provide member states with enhanced veto options in situations where national interests are at stake. This is intended to ease the concerns of reluctant governments in the EU. A safety net is particularly relevant in the area of cyber foreign and security policy, where decisions need to be respectful of national sensitivities and political circumstances. The cybersecurity realm, given its complexity and direct impact on national security, serves as a favorable testing ground for understanding and discussing the effectiveness of these safety nets in balancing national sovereignty with collective EU interests.

CFSP and cyber

Over the past decade, the EU has launched several key initiatives to enhance its cybersecurity capabilities, reflecting the importance of this sector within the CFSP and for the Union’s security. The EU’s Global Strategy 2016, notably recognises cybersecurity as a “cross-sectional” policy task, essential to various EU policy areas, including internal and external security, and both civilian and military cooperation. According to Article 24(1) TEU “the Union’s competence in matters of common foreign and security policy shall cover all areas of foreign policy and all questions relating to the Union’s security” – thereby including cybersecurity.

The need for coordinated responses at the EU level to cybersecurity challenges is highlighted by the 2019 Cybersecurity Act, which clearly states that large-scale cyber incidents “necessitate effective and coordinated responses and crisis management at Union level, building on dedicated policies and wider instruments for European solidarity and mutual assistance”. In June 2017, the EU adopted the framework for a joint EU diplomatic response to malicious cyber activities (the so-called “cyber diplomacy toolbox”, CDT). This framework primarily sets out non-military measures under the CFSP that could contribute to “the mitigation of cyber security threats, conflict prevention and greater stability in international relations”. It includes restrictive measures (e.g. sanctions), which fall under the Union’s competence as laid down in Article 29 TEU and 215 TFEU. In July 2020, the very first, and so far only, cyber sanction regime was adopted.

In addition, already in 2013, the EU Cyber Security Strategy (updated in 2017) referred to the so-called “solidarity clause” laid down in Article 222 TFEU where the Union and member states are obliged to combine their efforts and “shall act jointly in a spirit of solidarity” to “assist a member state in its territory, at the request of its political authorities, in the event of a natural or man-made disaster”. The European Parliament (EP) even went a step further and mentioned cyberattacks as a reason to invoke the so-called “mutual defence clause” laid down in Article 42(7) TEU.

However, despite these advancements, the EU’s cyber defence remains a work in progress and focuses primarily on civilian capacity-building efforts. In sum, cyber foreign and security policy is a growing concern for the EU, which is not reflected in the overall CFSP output.

Low CFSP output in cyber as vulnerabilities increase

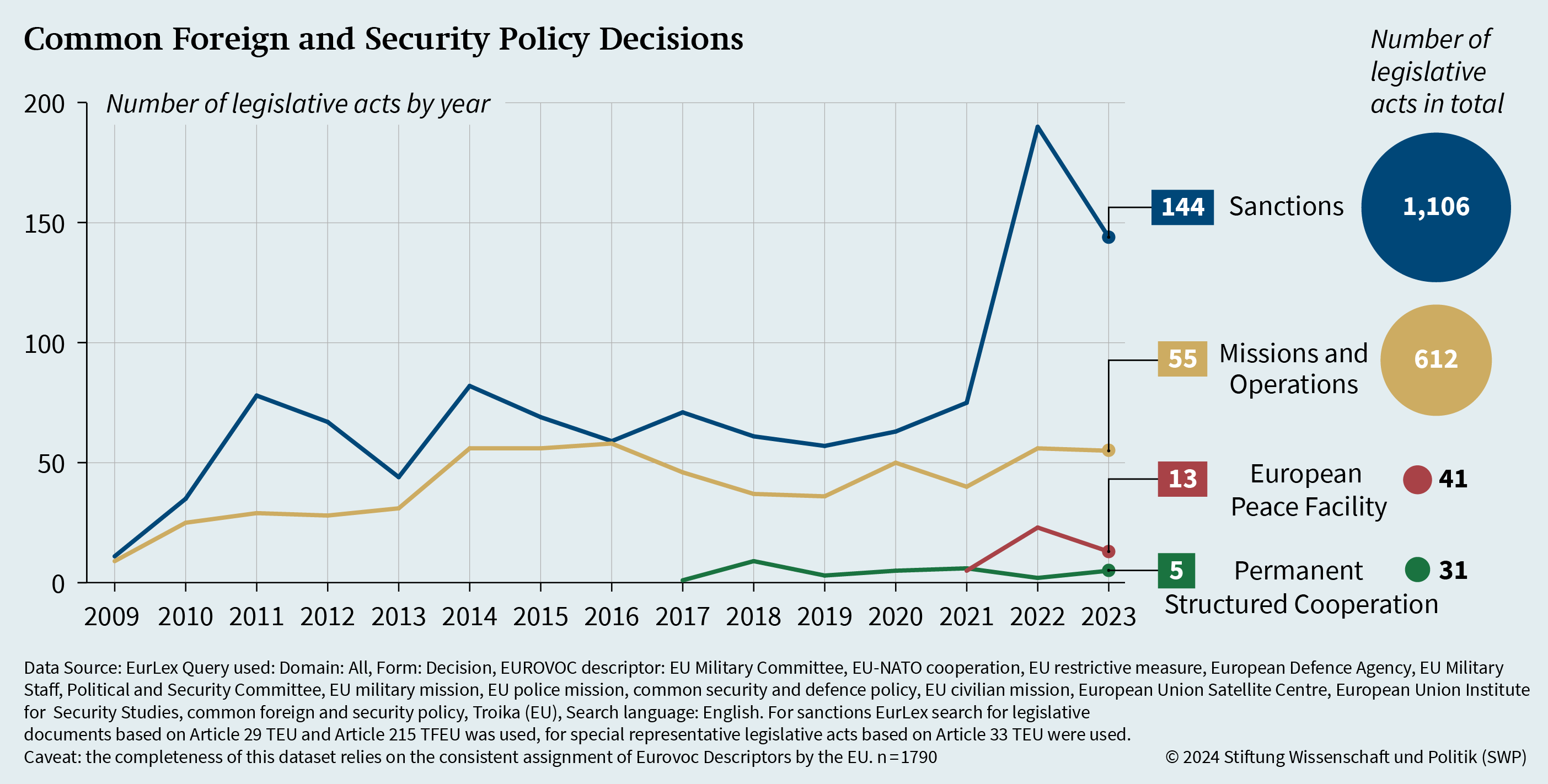

The gap between the expectations directed at the CFSP and its capabilities has been a longstanding issue. The overall output of CFSP decisions has shown stagnation since 2009 across all instruments, except for restrictive measures (sanctions) (see Figure 1). When empirically looking at the application of four CFSP instruments considered in this analysis – missions and operations, the use of the European Peace Facility (EPF), Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and restrictive measures – it becomes evident that there has been a notable increase in the number of sanctions, particularly since 2021. Specifically, in the cyber and information space, the number of CFSP decisions is particularly low, with only nine out of the 1,790 decisions examined relating to hostile cyber activities (including restrictive measures). This trend applies across the different instruments.

Since the Treaty of Lisbon took effect in 2009, there have been 1,106 decisions related to sanctions, establishing around 35 different sanctions regimes targeting states, organisations, and companies. However, the first and only CFSP decision directly addressing cyberattacks was enacted in 2019. In addition, the Union has never explicitly stated that legal attribution should be solely the responsibility of member states, with the exception of cases involving cyber sanctions.

Regarding decisions on missions or military operations, there have been 612 such decisions since 2009, peaking at 170 between 2014 and 2016 and 111 between 2022 and 2023. In practice, the EU has initiated or conducted over 40 missions and operations on three continents. As of March 2024, 22 missions and operations of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) are still active, including 12 civilian missions and nine military operations. The EU Partnership Mission Moldova (EUPM Moldova) launched in May 2023, however, was the first EU civilian CSDP mission to focus on fighting hybrid threats, cybersecurity, and foreign informational manipulation and interferences and crisis management. In addition, the EU Military Assistance Mission in support of Ukraine (EUMAM Ukraine) aims to enhance the military capacity of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, including building their long-term resilience in cyber defence.

Although the European Peace Facility was introduced only in 2022, 41 decisions on military empowerment measures have been taken since then. The first EPF used to support cyber defence in the Republic of Moldova was initiated in 2023.

PESCO also currently remains at a low level, despite the ambitious political agenda for establishing a European Defence Union, with only 68 projects based on 31 decisions. Out of the current 12 ongoing PESCO projects on cybersecurity, only three are focused on cyber defence. These include the establishment of a Coordination Centre for the Cyber and Information Domain, Cyber Rapid Response Teams, and a platform for information exchange on cyber threats.

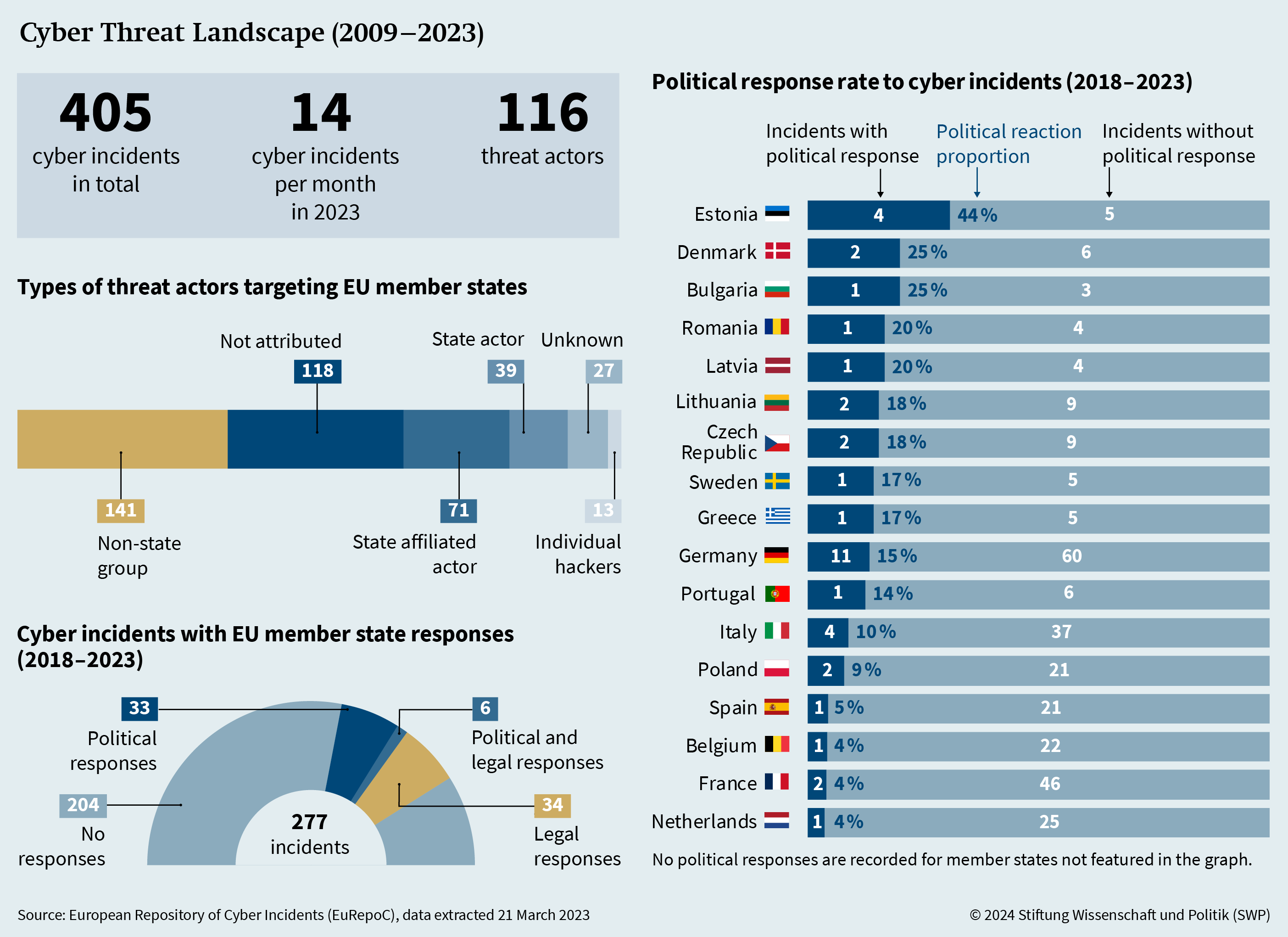

While the gap between expectations and capabilities remains, vulnerabilities in the cyber and information space continue to mount. The challenge for the EU here is that the strategic gains from cumulative cyber campaigns are higher than the restrictive measures taken by the EU against these threat actors. Data from the European Repository of Cyber Incidents (EuRepoC) can serve to illustrate the rising vulnerabilities and the limited activity in its foreign and security policy to retaliate against these threat actors (see Figure 2). As of March 2024, the dataset lists around 2,700 serious cyberattacks, 405 of which targeted EU member states and emanated from 116 different threat actors. Additionally, EuRepoC data show that since 2009, a large proportion (44%) of the serious cyberattacks against EU member states, targeted critical infrastructure organisations vital to the functioning of society – predominantly within the transport and financial sectors.

The Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox (CDT)

The CDT should serve as an EU instrument to help address these cyber threats. After all, it was intended to provide the EU with capabilities that would allow for appropriate joint diplomatic responses to cyberattacks, corresponding to the scope, extent, duration, intensity, and impact of the respective attacks. Its goal was to establish a basis for proportional, appropriate responses to cyberattacks. Low-threshold attacks typically result in the EU issuing a protest note or summoning an ambassador. In contrast, severe attacks prompt the implementation of targeted restrictive measures, such as freezing accounts or imposing travel restrictions. However, unanimity in the Council makes proportional, appropriate political and legal responses to serious cyberattacks almost, if not entirely, impossible. This was evident in the EU’s response to the KA-SAT incident, where unanimity prevented the imposition of additional sanctions against Russia, despite the attack’s disruption to Europe’s energy supplies.

Qualified majority voting (QMV) would help overcome obstacles to common action, as set out in the CDT implementing guidelines from 2023. The Council states that joint EU attributions taken by QMV facilitate exposing “the specific malicious cyber activit[ies] or specific actor, enable mitigating initiatives, promote the UN framework for responsible state behaviour, demonstrate capacity to identity its origin, discourage future malicious cyber activities, as well as to enable other response options to be used sequentially”.

However, to date, a not insignificant proportion (29%) of cyberattacks against EU member states since 2009 remain unattributed (Figure 2). The KA-SAT attack in February 2022 stands out as the only incident that has been officially attributed to a state by the governments of the US, UK, Canada, Australia, as well as by a statement of the High Representative (HR) of the EU. At the same time, very few cyberattacks were met with political or legal responses by EU member states since the launch of the CDT (14% and 14.4%, respectively). Rather, EU member states have primarily responded to cyberattacks with stabilizing (e.g. statements by ministers, deputies, or heads of government) or preventative measures (i.e. political declarations intended to point out growing cyber risks). In addition, there is a significant disparity in the rate of political responses to cyberattacks among member states, further highlighting the inconsistencies in current responses to cyber threats within the EU. For example, Estonia responded with political reactions to 44% of all cyberattacks it faced, while the Netherlands only responded to 4%. This may indicate that the EU member states’ countermeasures to cyber incidents are primarily political in nature and not necessarily proportional to the intensity of the cyberattacks.

Consequently, many perpetrators of these serious cyberattacks remain unaccountable and the lack of a uniform strategy or coordinated attribution process among the member states, let alone at the EU level, merely serves to exacerbate the issue. The unanimous decision-making required in the CFSP significantly hinders the EU’s ability to respond swiftly and effectively to cyber threats, particularly against critical infrastructure. On the other hand, QMV would allow the HR to take stabilizing measures, for example statements condemning states to stop its cyberattacks against the EU. Additionally, varying forensic capabilities and differing perceptions of threats among the member states further complicate the consensus needed for collective action. The diversity in threat perception and response mechanisms across the 27 member states highlights the need for a Europeanized or harmonized approach to cyber foreign and security policy. This is crucial not only for ensuring external protection but also for the smooth functioning of the (digital) internal market and its associated value chains.

Cyber foreign and security policy is a relatively new aspect of EU policy which, owing to its technological nature, has experienced limited politicization to date. Cyberattacks not only have a transnational impact but also pose a threat to the security of the entire Union, its member states and citizens. Therefore, fulfilling the protective role within the framework of the CFSP is absolutely necessary.

QMV roadmap in cyber

Increasingly faced with cyber threats, it is imperative for the EU to focus more of its efforts towards safeguarding critical infrastructure. Enhancing resilience and improving crisis management, while upholding international law, are crucial steps for the EU and its member states to adapt to such challenges. Qualified majority decisions in the Council of the EU in European foreign and security policy should proceed cautiously, variably, and according to a clear roadmap. EU foreign and security policies should be decided by QMV, as they necessitate an immediate and effective crisis response. This would help to broaden the fundamental understanding of the pressing challenges and to extend the limits of the current technical or legal understanding of the CFSP/CSDP to tasks formulated in the Strategic Compass, such as combating hybrid threats or defending against cyberattacks. Ultimately, the roadmap should initially focus on technical and less controversial issues before addressing the politically contentious ones. The decision on whether the HR should make a declaration on behalf of the EU is to be determined by QMV. To this end, European foreign and security policy must fundamentally distinguish between technical resilience-related and politically sensitive sanctions: as a starting point, the application of instruments such as preventive cooperation or stabilizing measures with third countries should be initiated. Most of the preventive measures are so far directed towards friendly neighbouring countries of the EU. However, cooperative measures such as dialogues could be enlarged to authoritarian states. For example, QMV would allow the EU to engage in capacity-building efforts with other regional organisations such as the African Union (AU). After successful collaboration in the first phase, member states could then move to the second phase and expand their ambitions to the application of restrictive measures. In the third and final phase, coercive measures according to international humanitarian law could be added to complete the spectrum of powers. The timetable for transitioning from one phase to the next should be determined by the member states in cooperation with the national parliaments and the EP.

Sovereignty safety nets

Integration steps in the field of European foreign and security policy, and particularly the introduction of QMV, often fail due to the national reservations of some member states, which see their vital national interests threatened. Therefore, current discussions on reforming the CFSP largely focus on expanding the sovereignty safety net. The safety net solution is intended as a political arrangement agreed by all member states, akin to the “Luxembourg Compromise” initiated by the French government back in 1966 when QMV was first introduced in certain areas by the Treaty of Rome. This compromise gives member states an informal veto right in decisions made by the Council of Ministers where QMV is stipulated by the Treaties of Rome, when they believe their national interests are at stake. The Group of Friends on QMV is currently discussing such options to facilitate the introduction of more QMV specifically within the CFSP.

The Treaties already provide for the use of QMV within the CFSP in specific cases referred to in Article 31 (2) TEU and through the “passerelle clause” of Article 31 (3) TEU. However, this does not apply to CFSP decisions with military or defence implications. In addition, an “emergency brake” is foreseen by Article 31(2), whereby any member state can object to a decision being taken by QMV for “vital and stated reasons of national policy”. Based on the “passerelle clause”, the Juncker Commission proposed back in 2018, the gradual extension to three areas of EU foreign policy: EU positions on human rights in multilateral fora; the adoption and amendment of EU sanctions regimes; and the civilian CSDP. In order to strengthen the resilience and security of the EU as such, the application of QMV could also be considered within the framework of cyber foreign and security policy.

Expanding the sovereignty safety net may facilitate building political consensus for incorporating more QMV into the CFSP. However, it should be complemented with special accountability obligations when member states exercise their veto. Ensuring vital interests in the context of improving the CFSP can be discussed along with the need for a more effective EU cyber foreign and security policy. To claim national interest reservations, factual, political as well as concrete threat situations for the Union and its member states should also be taken into account. Therefore, QMV in cyber foreign and security policy should be supplemented with special accountability obligations regarding the threat situation of the Union and its member states.

Moreover, while the treaty provides various options for member states to safeguard their interests and even delay or halt EU action (including actions based on the principle of sincere cooperation (Article 4 (3) TEU) and loyalty and mutual solidarity (Article 24 (3) TEU)), constructive abstention under Article 31(1) subparagraph 2 of the TEU uniquely allows for the protection of national interests without obstructing Union action. Any member of the Council that abstains from voting can justify their abstention with a formal declaration. In this case, the Council member is not obliged to apply the decision but agrees that the decision is binding for the Union. Hungary has already made use of constructive abstention in providing military equipment to the Ukrainian armed forces through the EPF. However, if member states who abstain represent at least a third of the member states, constituting at least a third of the population of the Union, the decision will not be adopted. Further emphasizing the use of constructive abstention could prove to be another simple means of safeguarding national interests while enabling Union action within the CFSP without necessitating amendments to the treaty.

Passerelle clause and Article 31(3)

Given the cumulative effects of cyberattacks under the threshold of an armed conflict, especially against critical infrastructure, recourse to the “passerelle clause” would be advisable. If the special “passerelle clause” in Article 31(3) TEU for introducing QMV into cyber foreign and security policy were activated, the discussions could be followed by a political declaration. In this declaration, it should be considered that recourse to a national interest should not impair the Union’s ability to act in preventing concrete danger.

A “passerelle” decision according to Article 31(3) TEU, containing a new safety net, could serve as a starting point for discussions to bring all 27 member states on board, but it should also avoid the negative external effects of individual state behaviour. A safety net for Article 31(2) TEU (in addition to the existing possibilities) should take into account the validity of the national interests presented in each case according to the cyber threat situation. This could then be reviewed by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), and through tools such as a European Repository on Cyber Incidents.

The costs incurred by recourse to the national interests of the member states, which subsequently impede Union action in danger prevention, should be included in the justification. The costs of non-action or cyber (in)security for the EU and affected member states should be considered in a political declaration on recourse to national interests.

Political declarations required

The previous proposals for sovereignty safety nets have been purely legal and technical and less political in nature. In view of the EU’s current geopolitical situation, there is a compelling case for mandating that member states provide political justifications when invoking national interests. These justifications should address the broader impacts on other member states, particularly concerning the protection of critical infrastructure. When employing sovereignty safety nets, detailed explanations should be required and included in political declarations. Three arrangements need special attention: the emergency brake, the blocking minority, and the Ioannina mechanism.

Member states have the emergency brake instrument at their disposal, as provided for in Article 31(2) subparagraph 2 of the TEU. It allows a member state to oppose a decision by a qualified majority for important reasons related to national policy. In such instances, a vote is not conducted, and the High Representative seeks to negotiate an acceptable solution with the concerned member state. If the High Representative does not succeed, the Council can request to decide by qualified majority by referring the matter to the European Council for a unanimous decision. The definition of national interest in this context needs to be well-justified, ensuring it aligns with situations where protecting the national interest of one member state outweighs addressing the cyber insecurity of other affected member states, or the functioning of the internal market.

When the Council decides by qualified majority, a blocking minority requires at least four member states representing more than 35% of the EU’s population. If a blocking minority is formed, no decisions can be made. Regarding cyber foreign and security policy, invoking a blocking minority would be considered inadmissible if member states whose cybersecurity is less compromised than those directly affected by cyberattacks were to do so.

If the Council decides by qualified majority, the Ioannina mechanism (Council Decision 2009/857/EC) is also applicable. The mechanism obliges the Council to persist in discussions and seek solutions within a reasonable period if member states representing at least 55% of the EU population or at least 55% of the member states forming a blocking minority oppose the adoption of a legislative act by qualified majority. However, there is always the possibility of requesting a vote according to the Council’s Rules of Procedure. Resorting to the Ioannina mechanism would hardly be justifiable if it were to limit the cyber defence of individual members or the EU as a whole.

European sovereignty and strengthening the resilience of critical infrastructure can be more efficiently and effectively achieved by introducing QMV into the CFSP. Specifically, doing so could increase European operational capability in cyber foreign and security policy. Recourse to national interests that restrict situational awareness or European cyber defence should not come at the expense of European solidarity. A sovereignty safety net, which could facilitate member states’ willingness to take CFSP decisions by QMV and will be introduced by a political declaration, should always place common European interests above national ones.

Dr. habil. Annegret Bendiek is Senior Fellow in the EU / Europe Division at SWP.

Max Becker is Research Assistant in the EU / Europe Division.

Camille Borrett and Paul Bochtler are Data Analysts in the Information Services Department at SWP.

This SWP Comment is based on research conducted by the European Repository of Cyber Incidents (EuRepoC), a research consortium funded by the German Federal Foreign Office and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark where Annegret Bendiek is Principal Investigator.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2024

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C19