Whether and when the Gaza Strip will be rebuilt is uncertain in view of the renewed fighting between Israel and Hamas. Should this happen, the reconstruction plan presented by Egypt is likely to provide the blueprint. A network of economic and security actors centred around Ibrahim al-Argani – an entrepreneur with close ties to President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who has previously profited from the precarious situation in Gaza – stands to benefit in particular. Germany and its European partners who support the Egyptian plan should therefore insist on maximum transparency and accountability. Otherwise, there is a risk not only of disregarding Palestinian interests and incurring excessive costs, but also of further entrenching Egypt’s authoritarian system of governance.

On 4 March, the Arab League endorsed the plan for the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip drawn up by the Egyptian government. The Egyptian plan thus developed into an Arab initiative, which the governments of Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom also backed in a joint declaration. The plan contravenes the ideas of US President Donald Trump, who wants to transform the coastal strip into the “Riviera of the Middle East” and has at least initially proposed the displacement of Palestinians to neighbouring countries. Cairo wants to prevent such a scenario at all costs. The creation of an independent Palestinian state would thus be impossible for the foreseeable future. Above all, however, the establishment of Palestinian refugee camps on Egyptian territory would represent a considerable security risk from Cairo’s point of view. The Egyptian security apparatus fears that such a development could jeopardise internal stability and drag the country into conflicts between Palestinians and Israelis – leading to the risk of a direct confrontation with the neighbouring country.

The starting point of the Egyptian plan is therefore that the approximately two million inhabitants of the Gaza Strip remain in the territory, even during reconstruction. Beyond that, however, the 100-page document is more of a declaration of intent than a concrete plan. Three phases are envisaged: In the first six months, rubble is to be removed along the most important north-south connection in the Gaza Strip, temporary accommodations are to be erected and partially damaged residential buildings repaired. The second phase, which is expected to last around two years, will continue with the removal of rubble and the construction of supply networks and additional housing units. In the final phase, which is scheduled to last two and a half years, additional housing, an industrial zone, a fishing harbour, a commercial harbour and an international airport are to be built. A committee of technocrats would initially be responsible for coordinating humanitarian aid and paving the way for the Palestinian Authority to take over the administration of Gaza. An internationally mandated peacekeeping force would be responsible for security. This would be flanked by a political process geared towards a lasting conflict settlement in the spirit of a two-state solution. Regarding reconstruction costs, the plan draws on estimates by the United Nations (UN), the World Bank and the European Union. These put the total at US$53.2 billion, to be raised by various donors, including individual states and UN institutions. Cairo therefore aims to organise a donor conference as soon as possible.

However, Egypt’s reconstruction plan is driven not only by foreign and security policy considerations, but also by economic interests. Although the document does not explicitly assert a leadership role for Egypt, it does refer to the country’s “historical and regional role”, subtly suggesting that Egypt is well-placed to take the lead in this initiative. Moreover, unless Israel opens its borders, it is foreseeable that material supplies and logistics will be channelled largely through Egypt. Reconstruction would thus present a valuable opportunity for the Egyptian economy. Since taking office in 2014, President Sisi has set off a veritable construction boom in Egypt. Among the most prominent projects are the expansion of the Suez Canal and the development of a new administrative capital. The transport and energy infrastructure has also been massively expanded – often under questionable cost-benefit assumptions. However, in view of empty state coffers and high national debt, the government is able to award fewer and fewer lucrative contracts. The construction industry’s capacities, which have been expanded in recent years, therefore remain increasingly unutilised. The reconstruction of Gaza could provide new business opportunities here, but probably not for the entire sector equally. A network of contractors and security actors in particular could capitalise on the project.

The Gaza-Sinai connection

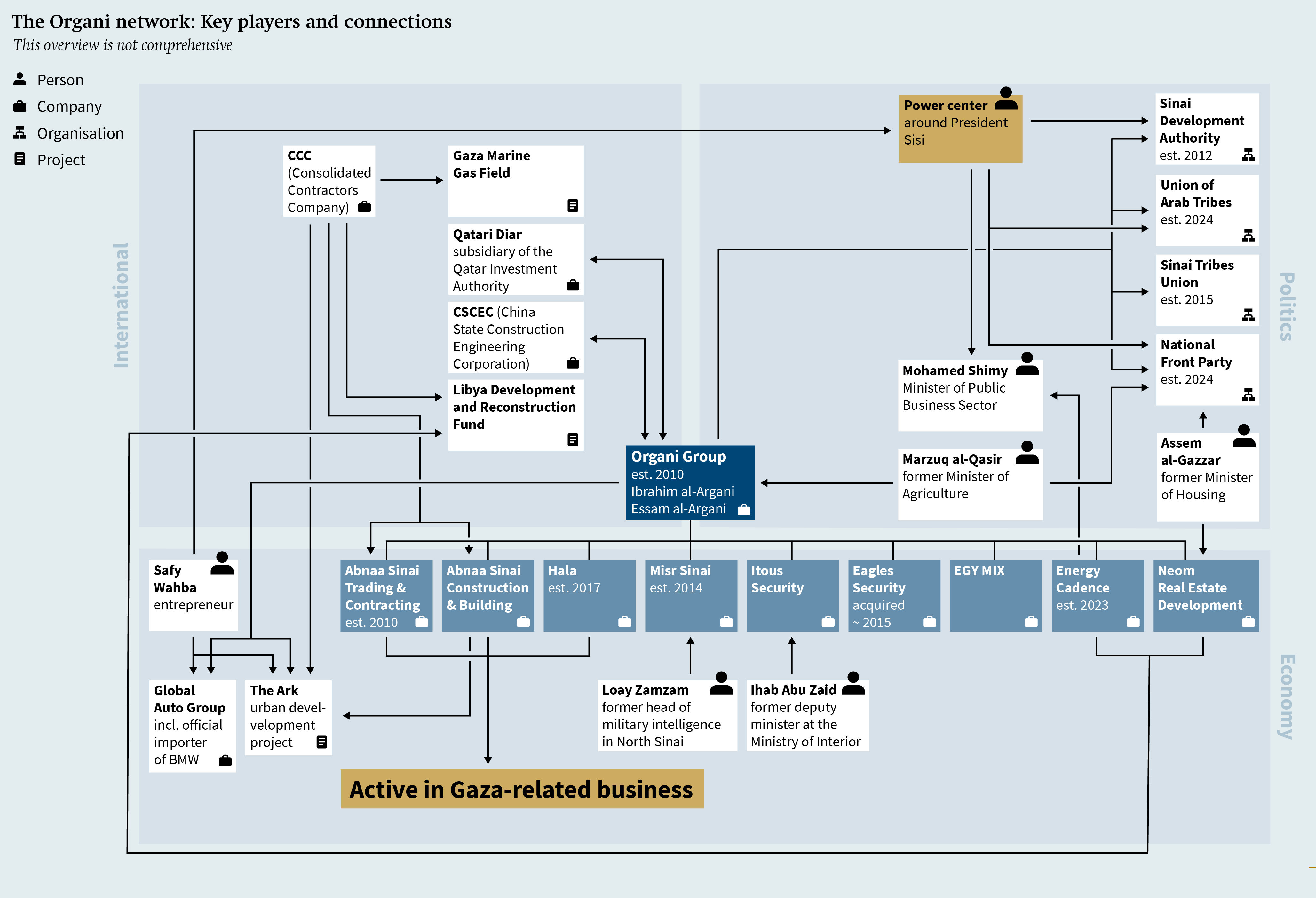

At the centre of this network is Ibrahim al-Argani, a businessman and tribal leader from the Sinai Peninsula. His entrepreneurial activities can be traced back to 2010, when he founded the Organi Group, the parent company of a diversified group of companies (see figure). With subsidiaries such as Abnaa Sinai, the company is involved in the construction of business districts in New Cairo as well as projects in the new administrative capital and the construction of sports and leisure facilities across the country. It is also active in the building materials sector with EGY MIX. In addition, the Group has invested in hotel complexes in recent years, particularly in the tourist centres of southern Sinai.

Organi also maintains business relationships with international car manufacturers, including BMW, through its stake in the Global Auto Group. With Itous Security and Eagles Security, the company is also active in the area of security services, such as for major events and foreign embassies. Outside Egypt, the Organi Group is primarily active in eastern Libya through its subsidiary Neom. It has benefited from extensive construction contracts from the Libya Development and Reconstruction Fund, which is headed by one of the sons of the ruling general, Khalifa Haftar.

The Group’s rapid expansion is all the more remarkable given that Argani was apparently involved in disputes with the Egyptian security apparatus in the 2000s. During this time, the northern Sinai Peninsula was the scene of repeated conflicts between state security forces and members of local Bedouin tribes, who were often involved in smuggling activities. Argani – a member of the Tarabin, the largest local Bedouin tribe – was arrested and only released from prison in 2010. Since then, there have been reports of close cooperation between him and state actors. Argani specifically used his tribal connections to support the Egyptian military in its fight against jihadist groups in the Sinai. Following the political upheaval in 2011 – and especially after the military coup in 2013 and the subsequent takeover of the presidency by Abdel Fattah al-Sisi – these groups engaged in civil war-like clashes with the armed forces in the northern part of the peninsula. The Sinai Tribes Union, which was founded in 2015 with the help of Argani, fought as an armed militia alongside the military – apparently committing significant human rights violations and recruiting minors.

The alliance between Argani and the Egyptian security apparatus opened up an extremely lucrative source of income for the entrepreneur: the border traffic business between Egypt and Gaza. Since 2017, Hala, a subsidiary of the Organi Group, has been offering a “travel and tourism service” to speed up the official exit and entry process to Egypt, which could often take months via the border crossing in Rafah. Since then, Hala has taken care of obtaining exit documents, travelling from the border to Cairo and, above all, ensuring that the names of those leaving appear on the lists presented to Egyptian border officials. Since the outbreak of war in October 2023, the number of people wishing to leave Gaza has risen rapidly. According to the United Nations, 1.5 million Palestinians had already been displaced from their homes by the beginning of November 2023. After the start of the war, it was only possible to leave the Gaza Strip via “coordination” with Hala, which was quietly tolerated by the Egyptian authorities. The sums involved were remarkable. Some reports speak credibly of up to US$5,000 being paid to Hala per person leaving the country. Even with conservative estimates of 100,000 departures, this would be revenue of hundreds of millions of US dollars.

Organi Group companies have also played a central role since at least 2018 in supplying the Gaza Strip with vital relief supplies. Even before the war, the Gaza Strip’s economy was dependent on the import of humanitarian aid and commercial goods. Due to the Israeli blockade, the supply situation was subject to considerable fluctuations, determined by the volume of permitted deliveries.

Since the start of the war, the humanitarian situation has deteriorated significantly, with Israel increasingly restricting access. As a result, the flow of goods into the Gaza Strip has been severely disrupted. In this context, there have been growing reports of high transportation fees being charged in connection with the delivery of humanitarian aid. Attention has particularly focused on Abnaa Sinai, a subsidiary of the Organi Group, which has been benefiting from its de facto monopoly position in border traffic. It apparently took over most of the Red Crescent’s tasks in handling aid deliveries, operates its own warehouses and even carries out its own inspections to prevent commercial smuggling. Together with the long waiting times caused by Israeli controls, its high fees have driven up the price of food in the Gaza Strip and contributed to the worsening of the already catastrophic supply situation.

Interdependencies with politics

In addition to its lucrative operations on the Sinai Peninsula, the Organi Group not only expanded geographically, but also moved into an increasing number of business sectors. Throughout this expansion, ownership structures within the Group remained largely opaque. However, close ties with the Egyptian state are obvious. Argani himself was appointed by President Sisi in 2022 as one of two non-governmental members of the Sinai Development Authority, which is responsible for development projects on the peninsula. Management positions within the holding company are often occupied by former politicians and officials from the state administration (see figure): Organi Group’s Chief Financial Officer is former Agriculture Minister Marzuq al-Qasir; Neom Real Estate Development is headed by former Housing Minister Assem al-Gazzar; the security company Itous Security is run by former Deputy Minister Major General Ihab Abu Zaid (who was apparently responsible for tax affairs in the Ministry of Interior for a period of time in 2015); and Major General Loay Zamzam, the former head of military intelligence in northern Sinai, is deputy chairman of Organi subsidiary Misr Sinai, a company in which the Egyptian military holds 51 per cent of the shares. The Organi Group also maintains business relationships with other politically well-connected companies, including the conglomerate owned by Safy Wahba, whose son is married to a niece of President Sisi.

These entanglements with the state and within political circles have increasingly come under the scrutiny of the few remaining independent media outlets in Egypt over the past two years. An investigative report on Argani in the well-known non-governmental online journal Mada Masr atttracted so much attention that even the New York Times reported on the businessman. Despite criticism that he had enriched himself through the suffering of Palestinians, as suggested by these reports, Argani’s network continued to grow, with his political influence in particular becoming increasingly visible. In May 2024, the entrepreneur founded the Union of Arab Tribes (UAT), which he has chaired ever since. The UAT sees itself as a representative body for all tribes in Egypt, but it is by no means driven by opposition to the government. It explicitly supports President Sisi’s agenda, with the president himself holding the honorary chairmanship.

In July 2024, President Sisi appointed Mohamed Shimy – the then head of Energy Cadence, the energy division of the Organi Group – as Minister of Public Business Sector, giving the network a direct line to the government for the first time.

And at the end of December 2024, Assem al-Gazzar announced the founding of the National Front Party and became its chairman. Marzuq al-Qasir, head of finance at Organi Group, was appointed secretary general. The founding committee of this party also included Essam al-Argani, Ibrahim al-Argani’s eldest son, who is playing an increasingly important role as CEO of the Organi Group. Ibrahim al-Argani himself is one of the main financial backers of the new party.

The founding of the party in particular caused a considerable public stir, as its members and officials include numerous prominent figures from politics and business – including Diaa Rashwan, chairman of the State Information Service, Egypt’s official media and public relations apparatus, which reports directly to President al-Sisi. In recent years, Rashwan has also coordinated the National Dialogue, a social consultation process initiated by President Sisi under state control. Egyptian human rights organisations describe it as a farce, asserting that it ultimately only serves as “window dressing” of the authoritarian regime. Rashwan’s involvement in the founding of the party indicates that the National Front Party will play a dominant role in the parliamentary elections scheduled for the end of 2025 and is intended to establish itself as the new ruling party in order to further strengthen Sisi’s power base. Above all, however, his involvement underlines how closely the network around Argani is intertwined with the power centre under President Sisi.

Ready for reconstruction

In a press conference in February 2025, Essam al-Argani announced that the Organi Group was keen to participate in the reconstruction work in the Gaza Strip. Compared to other construction companies that had also expressed interest, the Organi Group should have a clear advantage thanks to its quasi-monopolistic position in the handling of border traffic and its formidable political connections. Construction vehicles from Organi-owned companies were already working in the Gaza Strip in February 2025, after the ceasefire came into force. The company can also draw on experiences gained in the period after the war by Israel and Hamas in 2021. Unlike after previous wars, Egypt had at the time announced its leading role in reconstruction and even pledged US$500 million for this purpose. However, the focus of Egypt’s commitment was less on repairing damaged buildings and infrastructure and more on new construction projects, which were not realised by Palestinian companies but by Abnaa Sinai. Due to the lack of transparency surrounding these activities, it is also impossible to understand how much of the announced sum was actually channelled to Gaza. At the same time, Palestinians complained about the sometimes horrendous prices for building materials. These prices were apparently also a result of the quasi-monopoly that the Organi Group had for supplying the Gaza Strip – a situation that was itself a result of Israel’s blockade policy. This policy, together with a lack of funding, was already a major obstacle to reconstruction.

However, compared to 2021, the reconstruction now planned would have a completely new dimension – 92 per cent of residential buildings have been destroyed or damaged, and it could take 15 years just to clear the rubble. According to the Egyptian reconstruction plan, around 200,000 residential units would have to be built in the first two years, at an estimated cost of US$20 billion. Organi Group companies would not be able to cope with a project of this scale on their own. However, with the help of its political network and its role in operating the border infrastructure, it could take on a kind of gatekeeper function: Companies wishing to participate in the reconstruction process would have to cooperate with the Group or act as subcontractors.

This could explain why foreign governments are also interested in doing business with the Organi Group. Immediately after the UAT was founded in May 2024, a Qatari delegation paid a visit to Ibrahim al-Argani at the UAT headquarters. Around a month later, a subsidiary of the Qatari sovereign wealth fund QIA signed contracts with the Organi Group for three large-scale property projects in Egypt. And in February 2025, Organi Group and China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) announced a strategic partnership with a planned investment volume of up to US$5 billion within the first three years.

In view of the reconstruction of Gaza, Organi Group’s close business relationships with the multinational construction and energy company Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC) could also gain significance. CCC has cooperated in several Organi Group projects, including the construction of the Abnaa Sinai headquarters, the urban development project “The Ark” in Cairo and the construction of bridges in Derna, Libya. The company is controlled by the Palestinian Khoury family, which has close ties to the Palestinian Authority under President Mahmoud Abbas. Together with the Palestine Investment Fund, CCC holds the majority of the development rights of the Gaza Marine gas field, which is located 35 kilometres off the coast of the Gaza Strip. In 2021 and 2022, agreements were reached with the state-owned Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (EGAS) to allow private Egyptian companies to participate in the project and potentially import gas to Egypt. The war put a stop to these plans. However, in the event of reconstruction, the issue of developing the gas field is likely to be back on the agenda, as the associated revenue is urgently needed for reconstruction. Thanks to its connection to CCC and its political network, the Organi Group would then be in a strategically favourable position to benefit from future trade in Palestinian gas.

Outlook and policy recommendations

In mid-March 2025, Israel broke the ceasefire agreed in January and resumed military operations in the Gaza Strip. As a result, the prospect of rebuilding the area once again appears distant. The future status and administration of the territory and the role of Hamas remain key points of contention, for which no solutions are in sight. Above all, however, it is unclear whether the US administration and the Israeli government – at least parts of which are right-wing extremists – will even consider the continued existence of the Gaza Strip as a Palestinian territory. Not only President Trump’s “Riviera” remarks and statements by leading Israeli politicians, but also measures such as the Netanyahu government’s decision to set up an authority to promote the “voluntary” departure of Palestinians from the Gaza Strip make it clear that the forced displacement of the Palestinian population remains a possibility. Such an expulsion – whether deliberate or as a result of the destruction of livelihoods – would constitute a serious violation of international law and must be firmly rejected by Germany and its European partners.

Against this backdrop, the support of European states for the reconstruction plan drawn up by Cairo was an important political signal. Should this plan actually be implemented in the future, however, it should not be overlooked that implementation with the central involvement of Egypt harbours considerable risks – especially with regard to the role of the network around the Organi Group described above. There is a danger that the interests of the Palestinian side will not be given sufficient consideration, similar to the scenario involving reconstruction activities after 2021. This is not only about the adequate involvement of Palestinian companies and workers in the implementation, but also about the inclusion of Palestinian perspectives in the planning process. The sequence and weighting of measures outlined in the Egyptian plan should therefore be critically scrutinised. For example, the expansion of a port would be an important step towards improving access to the Gaza Strip – yet this aspect is given little attention in the Egyptian plan. Given the Organi Group’s central role in supplying Gaza, it is questionable whether Cairo has any real interest in fundamentally changing the current access routes. This highlights another key issue related to Egypt’s leading role in the reconstruction process: Costs could rise significantly – not only due to the Organi Group’s de facto monopoly in logistics and transport, particularly in the delivery of construction materials, but also because contracts may be awarded based on political loyalties rather than economic efficiency. In this way, the reconstruction process risks contributing towards the further consolidation of Egypt’s authoritarian power structure. By favouring loyal business actors, the political leadership under President Sisi could further strengthen the existing politico-business network centred around the Organi Group – thereby cementing and expanding its own hold on power.

As much as Germany and its European partners should support the Egyptian reconstruction plan and its integration into a broader diplomatic process aimed at long-term conflict resolution – in order to create prospects for the people of Gaza – they should equally use their role as key donors to promote adherence to core principles during the plan’s further development. In particular, it is essential to consistently advocate for the broadest possible participation of Palestinian civil society in the ongoing planning process. Within the framework of the donor conference planned by Egypt, Germany and its partners should push for the establishment of an international fund under the umbrella of the World Bank – a proposal that has already been put forward by the Palestinian Authority. Such a fund would help ensure that resources are allocated transparently and based on actual needs, primarily benefiting Palestinian economic actors.

Felix Haschen was an intern in the Africa and Middle East Research Division at SWP. Dr Stephan Roll is a Senior Fellow in the Africa and Middle East Research Division.

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2025C16

(English version of SWP‑Aktuell 13/2025)