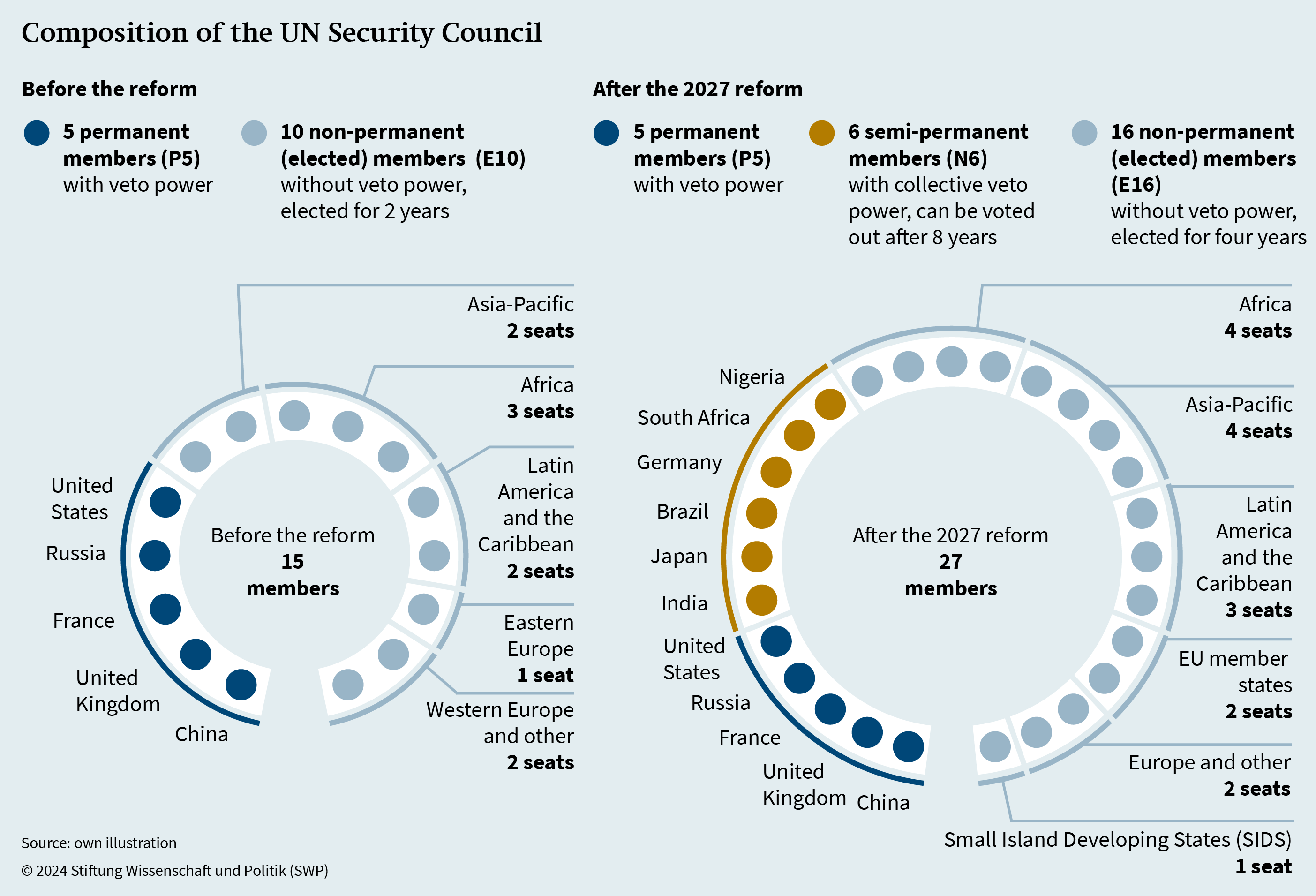

Surprise and jubilation in the United Nation Security Council (UNSC): 2028 begins with a bang. The permanent members of the body declare that they will voluntarily renounce their right of veto in cases of mass atrocities. This self-limitation, achieved after a long struggle, would have been unthinkable without the far-reaching reform of the Security Council that preceded it. The initiative, based on an earlier Franco-Mexican proposal and the Code of Conduct of the Accountability, Coherence and Transparency Group (ACT Group), came from the new members of the enlarged UNSC. Since 2027, it has consisted of 27 instead of 15 members. Germany is among the new members. In her first speech after the enlargement, the German Ambassador to the UN noted with a wink that her country had hoped to be represented in 2027/28 even without the reform. After all, Berlin had already announced in 2023 that it would stand for election as a non-permanent member in 2027/28. However, it was not foreseeable at the time that Germany would now be one of the six new semi-permanent members of the Security Council.

In her speech, the German Ambassador looks back at the events that made enlargement possible. The main reason was the growing rift in the UN’s most important body, the UNSC, which was increasingly failing in its role as the guardian of world peace and international security. The rift between the five permanent members (P5) – Russia and China on one hand, and the United States, the United Kingdom and France on the other – had gradually become so deep that it was hardly possible to take any relevant decisions. At the same time, the threats to international peace and security had multiplied. Armed conflicts escalated and spread, for example in Ukraine, the Caucasus, the Middle East and the Horn of Africa.

Many UN observers agree with this assessment in principle. However, some also emphasise the power–political motives that were important for pushing through the reform. There had been a long-standing consensus that the Security Council, which was established in 1945 and expanded by six non-permanent members in 1965, no longer reflected the geopolitical realities of the 21st century. However, there had been disagreement on two issues, namely which states should become new members and what rights they should have. The second issue mainly concerned the veto power reserved for the P5. Even after the 2027 enlargement, the P5 initially retain their full veto. So far, the pro-reform camp has been unable to overcome the stubborn opposition of China, Russia and the United States in particular. However, the so-called New 6 (N6) – Germany, Japan, Brazil, India, South Africa and Nigeria, which have joined the UNSC as semi-permanent members – have the option of exercising a collective veto on decisions. If they reach a broad consensus among themselves, the N6 can also prevent the adoption of resolutions (provided these resolutions do not concern procedural issues that are generally not subject to the veto). The veto is effective if at least five of the N6 join in. Brazil enjoys a special position in this context: In accordance with the relevant regional representation in the UN, the veto rule for the N6 stipulates that all major geographical regions should have the opportunity to block a decision. Latin America and the Caribbean (Group of Latin American and Caribbean Countries) is represented solely by Brazil among the UNSC members with individual or collective veto rights. Therefore, Brazil’s rejection of an N6 veto is sufficient to prevent it.

Together with the now 16 instead of the previous nine non-permanent members of the UNSC, the N6 put the initiative for self-restraint with regard to vetoes in the case of mass atrocities on the agenda. While this would have been unthinkable a few years ago, the “old” P5 finally agreed on the condition that the N6 must also comply with it. However, Russia subsequently makes it clear that it will continue to veto any unfavourable resolutions concerning the protracted war in Ukraine. The vague wording of the declaration on “situations of mass atrocities” also remains a potential loophole. Usually, as in the Code of Conduct supported by more than 120 states, these atrocities include genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. However, only the first two are explicitly mentioned in the voluntary commitment of the P5 and N6. As crimes against humanity have not yet been codified in a treaty, there is a lot of room for interpretation, especially because no reference has been made to existing definitions such as those in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. In addition, the commitment does not include preventive measures, which means that it explicitly covers only mass crimes that have already occurred.

Nevertheless, the decision signals an unexpected new reform dynamic in the UNSC. It is primarily linked to the specific circumstances that allowed the body to grow to a size that had long been considered unattainable. The new members use the resulting momentum to launch an initiative, with broad support from the UN General Assembly (UNGA), to revive Article 27 (3) of the UN Charter. This sets a certain limit on the veto, as the permanent Security Council members are expected to refrain from using it if they themselves are a party to the dispute. After a few exceptions in the early years of the UN, the rule was later effectively ignored by the P5 and became largely irrelevant. Although it remains questionable whether this initiative can be enforced, it is another sign of new beginnings in the Security Council.

The long (and winding) road to enlargement: The end of a never-ending story

After the Cold War, reforming the UNSC became an increasingly prominent issue on the UN’s agenda in the 1990s. In 1993, the General Assembly set up a working group to deal with the future composition – as well as the working and decision-making methods – of the Security Council. The UN members agreed that greater legitimacy through appropriate representation and more effectiveness were important arguments in favour of reforming the UNSC. However, controversies remained regarding who should be appointed to this body and the exact modalities of a reform. Thus, little progress was achieved.

The mid-2000s saw a new push for reform. Against the backdrop of the deep controversies in the UNSC over the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, a group led by Brazil, Germany, India and Japan (G4) put forward concrete proposals for enlargement. They took up the so-called Ezulwini Consensus, in which African states had agreed to demand at least two permanent seats with the same rights as the P5, bringing the number of permanent members of a reformed UNSC to 11. The window for reform seemed to open at the 2005 UN World Summit, but ultimately the necessary two-thirds majority in the UNGA remained unattainable. In addition to the above-mentioned proposals, which were still relatively compatible with each other, there was another proposal to limit enlargement exclusively to additional non-permanent seats. The Uniting for Consensus group, which included regional rivals of the G4 such as Argentina, Italy, Pakistan and South Korea, campaigned in favour of this model.

Since 2008, intergovernmental negotiations “on the question of equitable representation and increase in the membership of the Security Council” had been taking place continuously, with little new momentum for comprehensive reform. At the same time, the UNSC was repeatedly divided over many crises and violent conflicts, from Libya in 2011 to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the political unrest in Venezuela in 2019. In the 2020s, the Security Council’s disunity peaked with Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine, Hamas’s attack on Israel and the subsequent military intervention in Gaza. The UNSC also proved increasingly unable to act on issues on which consensus had previously been reached – albeit after difficult negotiations – such as the fight against international terrorism and the renewal of mandates for existing UN peacekeeping missions. UN Secretary-General António Guterres spoke about a cascade of crises, including the coronavirus pandemic, faltering sustainable development, climate change and wars, and he lamented the parallel decline of multilateralism, including the blockade of the UNSC on important issues.

Following the New Agenda for Peace and the Summit of the Future 2024, there was a brief period of progress. This was the case, for example, with the UN’s support for regional peace efforts and the strengthening of the Peacebuilding Commission. However, neither a revitalised UNGA nor a more active role for regional organisations could compensate for the Security Council’s failure to act in the face of the multiple and manifest threats to peace and security. The opportunity created by a resolution at the end of 2023 to fund peace missions led by the African Union (AU), mainly from the United Nations assessed contributions, went largely unused.

At the same time, the two camps among the P5 were fiercely competing for support from countries of the Global South. The latter had been criticising its underrepresentation in the UNSC for decades and with increasing vigour. The steadily growing pressure for reform and the permanent crises in the 2020s, combined with the geopolitical and geo-economic calculations of the P5, ultimately created an opportune time for the expansion of the UNSC in 2027.

The new Security Council

In order to modify the composition of the UNSC, the UN Charter had to be amended. The hurdles for this were high: Any change required a two-thirds majority in the General Assembly and ratification by two-thirds of the UN members, including all permanent Security Council members. States wishing to amend the Charter in order to become members of the UNSC must therefore have both broad support among the 193 members of the General Assembly and the approval of the P5. The UN Charter itself sets out the requirements for non-permanent membership on the UNSC in rather general terms: contributions to the maintenance of international peace and security, and to the realisation of the other objectives of the organisation. Another criterion is the geographical distribution of seats. These criteria would also have to be applied to states aspiring to become permanent members of the UNSC. Against this background, the states seeking expansion of the UNSC had to agree on a common list of candidates and at the same time overcome the reservations of the P5, especially China and Russia, against a comprehensive enlargement.

Consensus among African states was crucial in drawing up the list of candidates. In view of the large number of plausible candidates, the selection process was difficult, especially as the Ezulwini Consensus masked rather than resolved the rivalries between them. The breakthrough came when the possibility of binding the desired permanent seats for Africa to the AU framework began to emerge – so that those states whose hopes were to be dashed could also agree. Nigeria and South Africa were finally nominated. On this basis, a list of candidates, which would be supported by more than two-thirds of the UNGA, was drawn up together with the G4.

The next challenge was to make the joint list acceptable to both camps among the P5. France, the United Kingdom and the United States were in favour of the G4’s accession ambitions. China and Russia welcomed the fact that long-standing members or founding states of the BRICS group, namely South Africa, Brazil and India, were to join. However, China in particular continued to have fundamental reservations towards Japan’s candidature, not least because of the history of both countries. Tensions were somewhat eased by the Japanese government’s announcement that there would be no more official visits to the controversial Yasukuni war shrine, a religious place of worship where Japanese war dead are commemorated, including some who were sentenced to death as war criminals after the Second World War.

Nevertheless, China, Russia and the Uniting for Consensus group continued to oppose additional permanent members in principle. It took a proposal from the L.69 – an important group of developing countries led by India that seeks comprehensive reform of the UNSC – to get the stalled reform effort moving again. In addition to new non-permanent seats, a future UNSC was to include a new category of six seats labelled “semi-permanent”. Initially, these were to be allocated to member states for eight years. After that, they can only be removed by a two-thirds majority of the UNGA, which simultaneously must agree on a replacement for the seat in question, taking into account the regional distribution of seats. Subsequently, the possibility of deselection will only arise after two consecutive terms of office. Thus, de facto uninterrupted membership is possible, but it is not designed to be permanent from the outset. This model, based on considerations already discussed in the context of the reform of the Council of the League of Nations in the 1920s, provided the basis for an agreement.

How the “devil in the details” was defeated

When a core group of states, including the G4, intensified the reform efforts, at first the disputes within the various regional groups over possible additional seats increased noticeably. However, with the help of a Pan African initiative, the AU found a regional solution that initially only included the seats for elected members from its circle. This formula was based on an agreement concerning the regional distribution of candidacies, so that each African sub-region is represented in the UNSC. Moreover, countries such as Kenya and Egypt, which were hoping for a semi-permanent seat, received the informal promise that they could take the first seat for an elected member from their sub-region. Ultimately, the key to achieving the reform was the ability of the regional groups to agree on a modus operandi that would facilitate the approval of states that could not themselves become semi-permanent members of the Security Council at this point.

After much back and forth, the European states agreed to dissolve the Eastern Europe as well as the Western Europe and Others regional groups. The European Union (EU) member states finally abandoned their original push for three non-permanent seats, but they combined this with the demand for a separate seat for the Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which are particularly threatened by climate change. As a result, both the EU member states and the remaining European (and other) states were each given two non-permanent seats. Germany promised to exercise its new responsibilities only in close coordination with its European partners while avoiding a conflict with France, which historically has been critical of the vision of an EU seat. However, Italy and some Eastern European states remained sceptical, fearing a reduction of their influence in the UN. In the end, African and European states agreed on a provision, according to which only the regional groups can call for voting out a semi-permanent member to the UNGA after eight years. In addition, no new member can be appointed if the majority of a regional group votes against it.

As expected, this consolidated proposal faced strong headwinds. Russia and China attempted to break up the growing consensus in favour of a comprehensive reform. They campaigned in favour of two new permanent seats for African states without a veto, but strictly rejected any other expansion. However, they did not succeed in driving a wedge into the reform camp. For one thing, their proposal was not compatible with the agreement concerning the regional distribution of candidacies. Secondly, it quickly became clear that this option would not only disadvantage some Western countries, but also hinder balanced representation overall. Furthermore, the United States signalled that it would not oppose an enlargement with such broad support.

As a result, the pressure on China and Russia increased. Since they had previously presented themselves as champions of the interests of the Global South, they now found it increasingly difficult to maintain their blockade. After a few adjustments – such as the collective veto instead of the individual veto initially envisaged for the new semi-permanent members – both finally gave in. Their expectation that the new weight of states from the Global South would strengthen their positions in the UNSC also contributed to this. China nevertheless tried to undermine the unified African position in order to prevent Japan from joining. But this threatened to alienate Beijing from the numerically strong bloc of African states. In addition, Japan’s gesture to ease the historically strained relationship with China was received favourably internationally. Although some regional opponents of the G4, such as Pakistan and South Korea, still voted against enlargement in the General Assembly, the necessary two-thirds majority was not in jeopardy. In essence, it was a back-door reform, with sceptical permanent members playing power politics and relying on their respective camps in the UNSC to emerge stronger. However, the bloc formation that many sceptics feared after enlargement did not materialise.

New dynamics after enlargement

At the first meeting of the enlarged Security Council, a fresh breeze was already blowing as a result of the change in composition. The N6 had worked towards a joint declaration – published before this meeting – with the now 16 elected members (E16). In it, the signatories called for a fresh start for the UNSC so that it could truly fulfil its responsibility for maintaining peace and international security. At the same time, they recognised their own responsibility for constructive cooperation in this regard. However, it also became clear that the continued individual veto power of the P5 would remain a potential bone of contention.

Contrary to expectations, the new members did not coalesce around the veto powers. Rather, the new structure – with three different categories of members and a different regional weighting – created a dynamic that continues to trigger further changes to this day, including the five original permanent members voluntarily agreeing to limit their right to veto. This was made possible due to a strong initiative by the E16 – supported by most of the new semi-permanent members as well as France and the United Kingdom – for the self-restraint of the veto-wielding powers. In the end, the United States, Russia and China agreed to waive their veto in situations of mass atrocities. Of course, the decision was later watered down in important points. Furthermore, reference to the concept of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), which is also extremely controversial among the new members, was avoided. However, the agreement highlights the opportunities available to UNSC members under the new conditions.

The new members also have strong positions on working methods and other Security Council issues. The basis for this is the coordination of common positions within some groups of countries, and it has already shown itself to be a recipe for success in the enlargement process. For reasons of work efficiency, it quickly proves advantageous for states to submit bundled motions and speeches so that discussions and resolutions do not get out of hand. The voting mode in the EU is primarily intended to bind Germany – as a new semi-permanent member – to common positions. In addition, the newly represented group of SIDS, for example, is creating its own forum to agree on candidacies. This forum is ultimately also used to coordinate voting on substantive proposals.

The dynamics in the UNSC are also changing as a result of the new majorities: 17 votes (out of 27) are now required for the necessary 60 per cent approval instead of the previous nine (out of 15). This means that the European, African and Latin American states, for example, have a joint majority, provided that the semi-permanent and permanent members from these regions join. At the same time, there can also be a majority without the Western-oriented states (i.e. the G7 plus like-minded states). China and Russia can organise a majority, but only if they succeed in getting all 15 representatives of the Global South on their side.

These majority ratios are one of the reasons why the P5 are not fundamentally renouncing the veto option. However, it is becoming more difficult for them to organise majorities for decision-making. In addition, the extension of non-permanent membership on the UNSC from two to four years increases the incentives for – and pressure on – the elected members to organise themselves better in terms of personnel and content.

The new German UN policy

Germany has significantly more opportunities to influence the work of the UN in this scenario. At the same time, the European partners expect close policy coordination. With its new semi-permanent seat, Germany enjoys special responsibilities, but only for a limited period of time, after which it will have to be indirectly confirmed by the regional group. Germany’s UNSC membership is thus clearly regionally embedded. In addition, since no blocs have formed in the Security Council, Germany must lobby for its own positions and for suitable partners, especially among the countries of the Global South.

Germany and the other N6 members are on permanent probation, so to speak. As such, they are accountable not only to their own regional group, but also to all members of the UNGA. Germany needs to make its own positions clearer, while at the same time aligning these standpoints with its closest partners to prevent them from becoming a source of division. Under the leadership of the Federal Foreign Office and in close coordination with EU partners, a comprehensive concept must first be developed for the organisation of Germany’s seat on the Security Council. Consultation with France, which as an “old” permanent member does not have to fear the disapproval of other EU members, is proving to be particularly delicate. Berlin must also find the right balance between maintaining close ties with the United States and intensifying cooperation with the new members of the UNSC.

In addition, the collective veto means that more coordination is required among the N6, whereby consensus with Brazil must always be secured. How difficult this can be is illustrated by the failure of a German-Japanese initiative on climate and security – closely coordinated with the SIDS – due to the objections of the new Brazilian government. On the other hand, the fact that German UN policy has increasingly dovetailed with German initiatives in the G20+ since the mid-2020s has paid off on several occasions. As a result, policy projects are being pursued in parallel in both forums, contributing to their success in the multilateral framework. Overall, the increased capacity of German foreign policy to set and implement ambitious agendas is beginning to bear fruit.

Dr Lars Brozus is Deputy Head of the Global Issues Division at SWP. Dr Judith Vorrath is a Senior Associate in the International Security Division at SWP.

|

* Foresight deals with conceivable events in the future. It offers insights on a fictitious event (not an analysis of real-life developments) with the aim of working through non-linear or unexpected developments. |

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C26

(English version of a contribution to SWP‑Studie 14/2024)